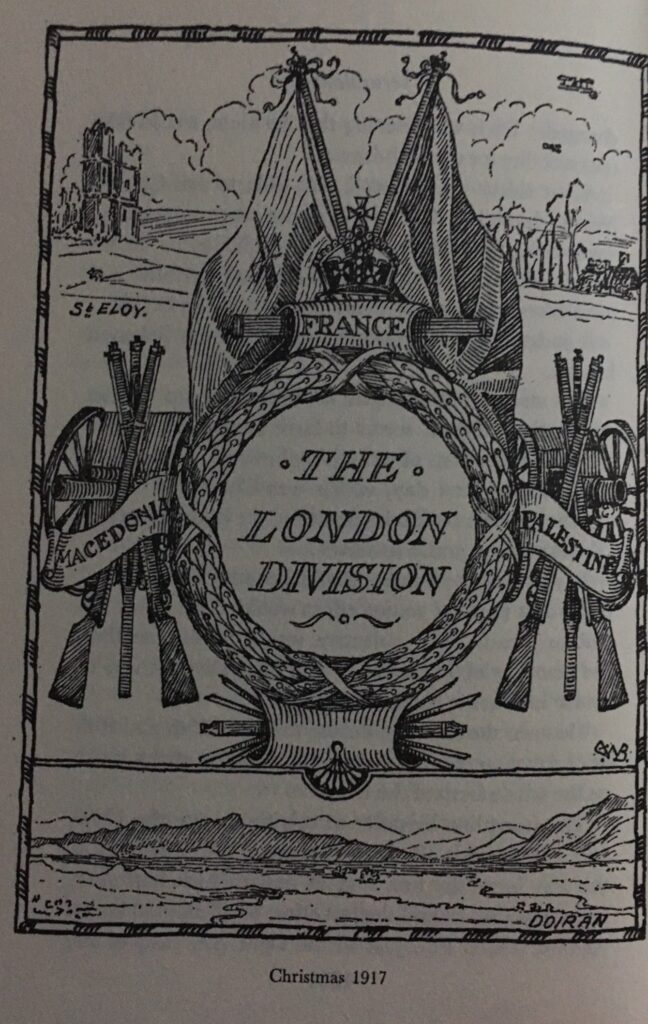

This is the story of three men from London who were involved in one of the pivotal events of the First World War – when Jerusalem was surrendered to the 60th (London) Division on the morning of 9 December 1917.

George Herbert Whyte, 2/18th (County of London) Battalion (London Irish Rifles)

When the conflict started in August 1914, George Whyte was living with his wife Mary at 13 Willfield Way in Hampstead Garden Suburb in North London. Whyte was then assistant manager of the Theosophical Publishing House and secretary to Charles Leadbeater, a leading figure in the Theosophical Society, which described itself as an “unsectarian body of seekers after Truth, who endeavour to promote brotherhood and strive to serve humanity.”

George and Mary Whyte had married in 1909 when he was 31. Mary was another Theosophy Society member and her elder brother, Charles, became a Liberal MP. A tea-totaller, non-smoker and vegetarian, George was inclined to pacificism and had served as a reservist with the Royal Army Medical Corps for four years before the war.

In 1914, Whyte volunteered to work in France as an orderly in a hospital unit set up by Leslie Haden-Guest, founder of the Anglo-French committee of the Red Cross and a future Labour MP and peer. This experience altered his outlook and he decided to fight and, in early 1915, Whyte returned to London and enrolled with the Inns of Court, Officer Training Corps. In August 1915, he was commissioned into the 2/18th London Regiment, a Territorial Force (TF) unit that recruited Londoners of Irish descent, and others like Whyte and his brother, who also joined the regiment in the First World War.

Charles Train, 2/14th (County of London) Battalion (London Scottish)

The second of the three men serving in Palestine with the 60th (London) Division was Charles Train. He was 24 years of age in August 1914 and living at 58 Chatterton Road in north Islington, just over a mile from what is now the Emirates Stadium the current home of Arsenal Football Club, although at that time the club was based in south London. The son of a Scotsman, Train was an employee of a London law firm and attended St Thomas’s, an Anglo-Catholic church close to his home.

At the outbreak of war, Charles Train was a member of the London Scottish Regiment, which he had joined in February 1909 soon after the creation of the Territorial Force. Included in the ranks of the London Scottish during the Great War were Hollywood film stars Ronald Coleman, Claude Rains and Basil Rathbone and it was the first TF unit to experience front-line fighting when its First Battalion participated in an attack on German lines at Messines Ridge in Belgium at the end of October 1914.

Train served with the 1/14th Battalion in Belgium in 1914 before being invalided home from France in March 1915. After a period of recovery, he had joined the Second Battalion, the 2/14th London Regiment, in Salonika and then moved with the battalion to Egypt in June 1917.

Morris Kassowitch, 2/20th (County of London) Battalion (Blackheath and Woolwich)

The third of the trio was Morris Kassowitch, who was 18 when the war began and was then living at 11 Luntley Place in the Whitechapel district of East London, which was home to the city’s largest Jewish community. Kassowitch was a tailor and lived with his father Harris, a sawmill worker, who had been born in Vilna (now Vilnius, the capital of Lithuania) and mother Kate, who came from Minsk (in what is now Belorussia). In 1914, both cities were part of the Russian Empire and it is not clear why and how Harris and Kate came to London but it is possible they were part of the massive Jewish exodus from Russia that following state-sponsored pogroms in the late 19th century. The oldest of eight children, Morris was born on 18 December 1896 and went to the local Chicksand Street Primary School.

It is believed that Kassowitch had joined up in 1915 and, by September 1917, was serving in the Middle East with the 2/20th London Regiment, which had its headquarters in Blackheath in south-east London.

The 60th (London) Division in Palestine

In June 1917, the 60th (London) Division had transferred from the Salonika front in northern Greece to supplement forces under the command of General Edmund Allenby, who had been appointed to lead the Egyptian Expeditionary Force (EEF), following a failure earlier that year to break Ottoman Army defensive lines around Gaza, the gateway to Palestine. The UK Prime Minister, Lloyd George had asked Allenby to capture Jerusalem as a “Christmas present” for the British people.

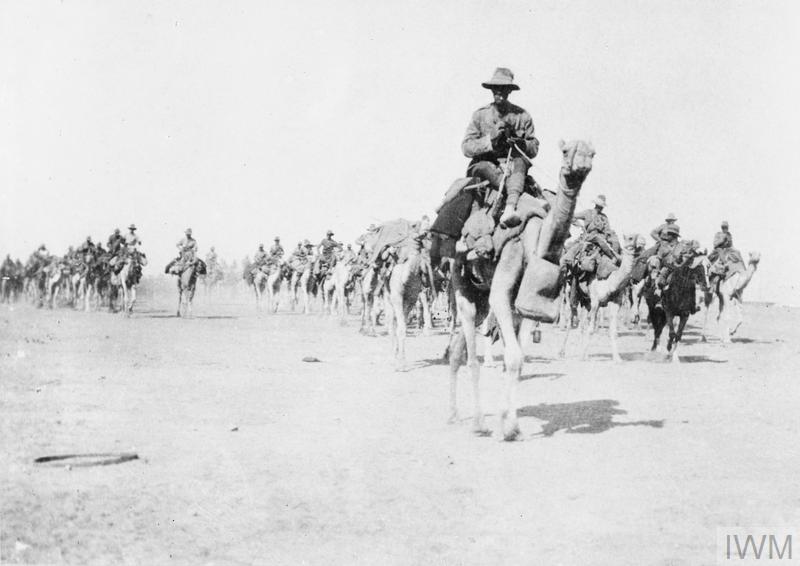

The EEF included two Army Corps and a Mounted Corps comprising horse-mounted soldiers from Australia and New Zealand. By the end of October 1917, Allenby was ready. A diversionary attack was mounted against Gaza by XXI Corps, while the main blow was struck by XX Corps and the Mounted Corps against Beersheba at the eastern end of the Gaza line in the Negev Desert.

The 60th Division were in XX Corps and advanced by night to starting positions south-west of Beersheba. The attack started with an artillery barrage at dawn on 31 October. The London Irish and the 2/20th Battalion were in 180 Brigade and held in reserve while the London Scottish in 179 Brigade advanced with fixed bayonets. All objectives were taken by noon and the capture of Beersheba was completed in late afternoon following a charge by the Australian Light Horse. On 6 and 7 November, XX Corps completed the destruction of the eastern end of the Gaza line.

Two weeks later, the division was called back into action. This time, the target was Jerusalem and the 60th Division entered the front line at the end of November. The London Irish and the 2/20th Battalion were deployed on Nebi Samwil, a high point north-west of the Holy City that commanded the approaches from the west.

The weather had broken and conditions were challenging and the decision was taken to take Jerusalem with an advance on a broad front on either side of the Jaffa to Jerusalem highway, the main road from the Mediterranean coast. The attack began in heavy rain in the darkness before dawn on 8 December. The London Irish stormed Turkish positions, known as the “Liver and Heart” redoubts and which overlooked the highway from the south. Both were quickly taken and, for his actions on this day, Whyte, by then a Company Commander, was recommended for the Military Cross. During the battle, the 2/20th Battalion had been held in reserve.

Meanwhile, on the same day, the London Scottish and the rest of 179 Brigade attacked Ottoman positions on high points at the southern end of the advance. On 8th December, Charles Train singlehandedly stormed a machine gun post and put it out of action and, for this remarkable deed, was recommended for the Victoria Cross. By evening, all the division’s objectives were taken and the Ottomans withdrew. That night, they abandoned Jerusalem.

What happened next is legendary.

Realising that the Ottomans had left, Jerusalem’s Mayor, Hussein al-Husseini, set out to surrender the city to the British Army under a make-shift white flag . As his party travelled west towards British lines, they encountered two cooks from the 2/20th Battalion, Kassowitch’s unit. The men declared themselves unqualified to accept Al-Husseini’s offer and this same story was repeated when he met two sergeants from the 2/19th Battalion later in the morning. Eventually, 60th Division’s Commander, General John Shea, arrived and formally sealed the capture of the city.

Two days later, Allenby and his military entourage would walk through Jerusalem’s western Jaffa Gate for the formal surrender ceremony.

The 60th Division soon passed through the city to the new front line on the road north of Jerusalem towards Nablus and orders were issued for the Ottomans to be pursued, with more territory expected to be seized before the onset of the worst of winter. It was a decision that proved fateful for men of the London Irish.

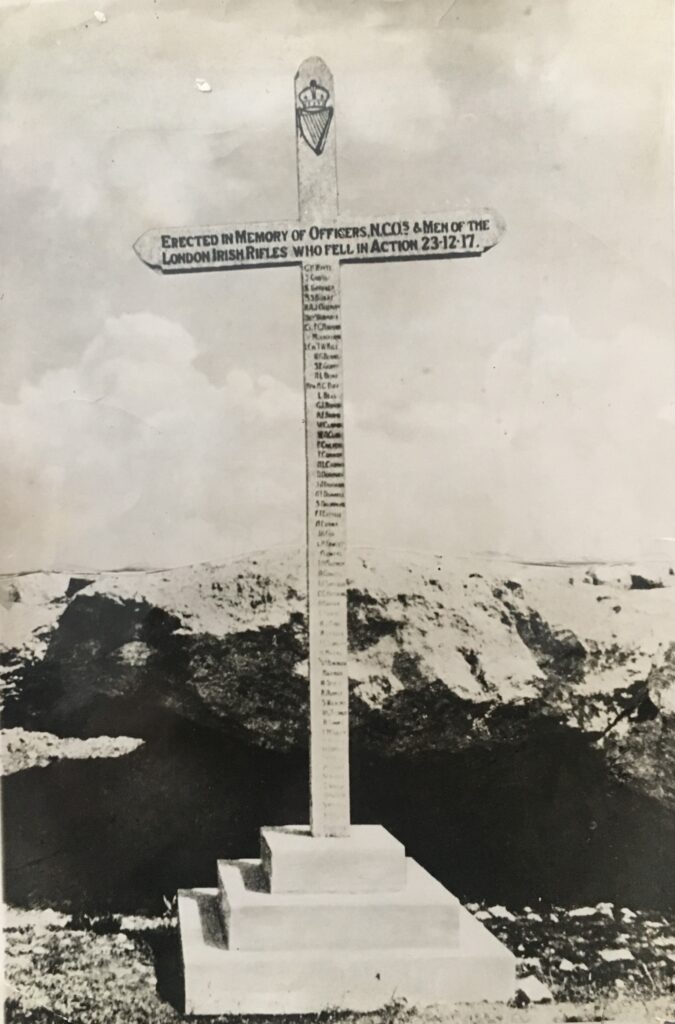

On 23 December, the 2/18th Battalion attacked Kherbet Adasseh, a high point west of the road that ran north to Nablus, and which was believed to be unoccupied, but the London Irish met well-trained Ottoman storm troopers and were devastated by fire from surrounding hills. In a single day, the battalion lost 60 men killed and suffered a total of 139 casualties, one of the worst days in the London Irish Rifles’ illustrious history. Among the dead was George Herbert Whyte.

At the end of December, an Ottoman counterattack along the Nablus road towards Jerusalem was repulsed and Allenby soon ordered a suspension in the advance until the weather improved.

In February 1918, the advance would resume when Allenby sent the 60th Division east to capture Jericho and, supported by the Australian & New Zealand Cavalry Division, take control of the Jordan valley. Before dawn on 20 February, this force attacked high points on both sides of Talat ed Dumm, a hill overlooking the road to Jericho and about 10 miles from Jerusalem. It was desperately hard work as the mountainous slopes are extremely steep and there were hidden opponents. The objectives were taken but a heavy price was to be paid. Among the casualties that the division suffered that day was Private Morris Kassowitch, who was wounded and evacuated, but died two days later.

In March and April 1918, the advance continued with two attempts to capture Amman by passing through the Moab hills east of the Jordan valley. The key objective was the Hejaz railway between Damascus and Medina, where an Ottoman garrison was under siege by Arab forces. These raids proved unsuccessful.

This period marked a turning point for the 60th Division as it was soon stripped of many of its London based battalions, who were transferred back to the Western Front. Among units sent to France was the London Scottish and the 2/20th Battalion, while the London Irish Rifles was disbanded, with most of its men being transferred onto the 10th (Irish) Division, although the majority of units in that division were now Indian ones.

We Will Remember Them.

When the war ended in November 1918, Charles Train left the army and later emigrated to Canada and he would live in Vancouver for the rest of his life.

But there was no going home for so many others and the 2,500 men who died fighting in the Holy Land in 1917 and 1918 rest eternally in the Commonwealth War Graves Cemetery on Mount Scopus in Jerusalem. They include George Whyte and Morris Kassowitch who live in history as two of the men who helped to capture Jerusalem in 1917.

A webinar about the Palestine Campaign of 1917 and the Transjordan attacks of 1918 is to be held at 1830 GMT on Wednesday 9 December 2020. It will be hosted by the Irish Brigade website and presented by Israeli historian Assaf Peretz and Edmund O’Sullivan of the Irish Brigade website.

The log-in details are as follows:

Zoom Meeting

Meeting ID: 875 6362 8658

Passcode: 407894