The Big Push to Rome was to begin in the middle of May 1944, and it would be the prelude to the Invasion of Europe in Normandy. None of the previous attempts to break through the German lines at the Garigliano, the Rapido, and at Cassino had met with complete success, and the time had now arrived for an effort which MUST succeed. The plan was to attack between Cassino Monastery and the sea on a frontage of about nineteen miles. Everything to the north was to be held as lightly as possible so that a big concentration of troops and supporting arms was available.

In the Liri Valley, Polish forces were to attack the Monastery from the north-west and to break through the mountains in a south-westerly direction with the idea of cutting Highway Six. This road was the enemy’s most vital artery, and it was known the Germans had orders to defend it at all cost. The 4th British and the 8th Indian Divisions were to force a crossing over the Rapido (Gari) frontally. The Fifth Army, with the French and American Corps, were to strike up in a north-westerly direction, capturing Monte Maio and Ausonia, with the idea of turning the southern bastion of the Liri Valley between San Giorgio and San Ambroglio. The Americans were to strike north-west from the Minturno-Castelforte area. An effective deception plan suggested that the Canadian Corps were going to land on the Lido di Roma! It is thought that that deceived the enemy completely and that he retained invaluable reserves to meet the bogus threat. The Allied forces in the beachhead at Anzio were to postpone any further major attacks until the hoped-for advance from the south had got under way.

In the Liri Valley, Polish forces were to attack the Monastery from the north-west and to break through the mountains in a south-westerly direction with the idea of cutting Highway Six. This road was the enemy’s most vital artery, and it was known the Germans had orders to defend it at all cost. The 4th British and the 8th Indian Divisions were to force a crossing over the Rapido (Gari) frontally. The Fifth Army, with the French and American Corps, were to strike up in a north-westerly direction, capturing Monte Maio and Ausonia, with the idea of turning the southern bastion of the Liri Valley between San Giorgio and San Ambroglio. The Americans were to strike north-west from the Minturno-Castelforte area. An effective deception plan suggested that the Canadian Corps were going to land on the Lido di Roma! It is thought that that deceived the enemy completely and that he retained invaluable reserves to meet the bogus threat. The Allied forces in the beachhead at Anzio were to postpone any further major attacks until the hoped-for advance from the south had got under way.

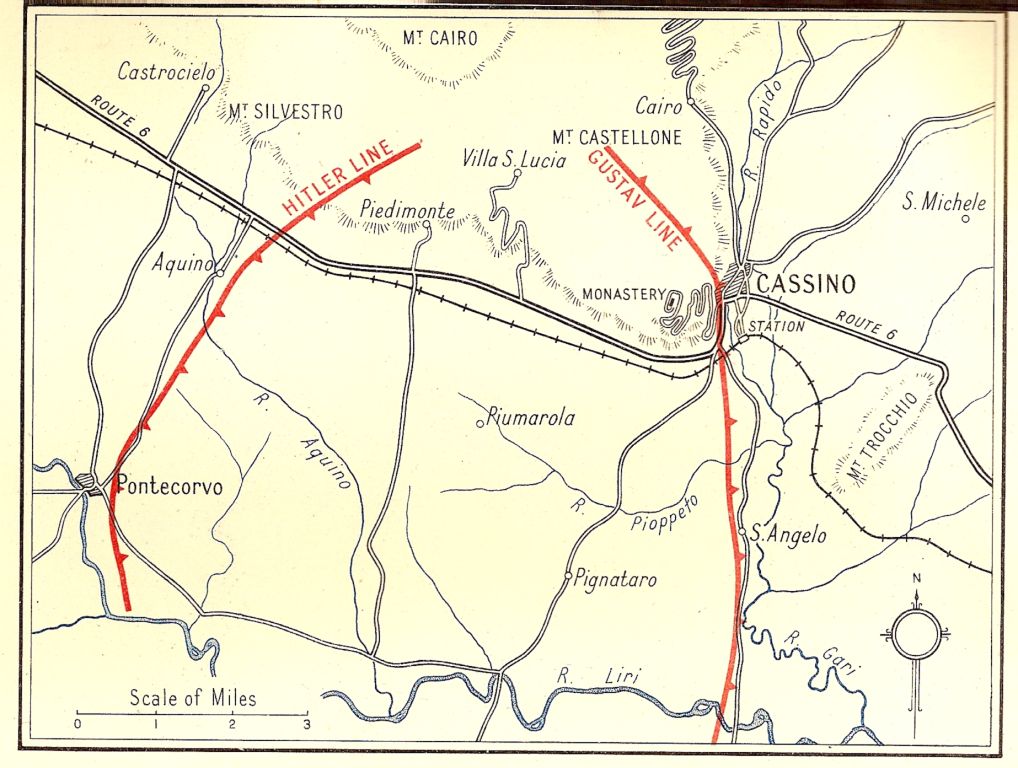

The 78th Division was to break through the bridgehead formed by the 4th Division, while the Canadian Corps were to do the same through the 8th Indian Division. After the Rapido, had been crossed these forces would smash through the Gustav Line, the 78th Division cutting Highway Six and linking with the Poles near Piedemonte and the Canadians going straight ahead towards Pignataro and Pontecorvo, which would link them with the successful French push. That vast, ambitious scheme, if carried out, would cause the Cassino garrison to pull out or be surrounded.

GENERAL ALEXANDER’S CONFIDENCE

As the great offensive opened against the main German defences in Italy, General Alexander, the Commander-in-Chief, in an Order of the Day to the troops said:

“Throughout the past winter you have fought hard and valiantly and killed many Germans. Perhaps you are disappointed that we have been unable to advance faster and farther, but I, and those who know, realise full well how magnificently you fought among these almost insurmountable obstacles of rocky, trackless mountains, deep snow, and in valleys blocked by rivers and mud, against a stubborn foe. The results of these past months may not appear spectacular, but you have drawn into Italy and mauled many of the enemy’s best divisions, which he badly needed to stem the advance of the Russian armies in the east.

Hitler has admitted that his defeats in the east were largely due to the bitterness of the fighting and his losses in Italy. This in itself is a great achievement, and you may well be as proud of yourselves as I am of you. You have gained the admiration of the world and the gratitude of our Russian allies. To-day the bad times are behind us and to-morrow we can see victory ahead. Under the ever-increasing blows of the air forces of the United Nations, which are mounting every day in intensity, the German war machine is beginning to crumble.

The Allied armed forces are now assembling for the final battles on sea, on land, and in the air, to crush the enemy once and for all. From east and west, from north and south, blows are about to fall which will result in the final destruction of the Nazis and bring freedom once again to Europe and hasten peace for us all. To us in Italy has been given the honour to strike the first blow.

We are going to destroy the German armies in Italy. Fighting will be hard and bitter, and perhaps long, but you are warriors and soldiers of the highest order who for more than a year have known only victory. You have courage, determination, and skill. You will be supported by overwhelming air forces, and in guns and tanks we far outnumber the Germans.

No armies have ever entered battle before with a more just and righteous cause. So, with God’s help and blessing, we take the field-confident of Victory.”

OPERATION DIADEM

The initial part of the operations on the Rapido was begun by the 4th Division and the 8th Indian Division on the night of May 11, and on May 14 the London Irish and the rest of the Irish Brigade hit the trail northwards and assembled behind Monte Trocchio. Here hundreds of guns joined in a bombardment of the German lines miles away. The enemy responded fiercely and so shells screamed overhead, passing both directions. A mass of men and vehicles were in the open, and as shells landed nearby from time to time there were a few casualties, though most of the men sought cover in slit trenches.

Smoke canisters were fired continuously to obscure the lower areas from the enemy high above in the Monastery, and thus much of their gun-fire was wild and inaccurate through lack of observation. The concentration of men and material would have been a valuable target for enemy aircraft, but thanks to fine work by the Allied air forces complete air superiority had been achieved. Indeed, a programme of close-support bombing was carried out to help the infantry across the Rapido and beyond. A senior officer of the RAF occupied a post on top of Monte Trocchio overlooking the battle-field, and there he controlled his “cab rank” of fighter-bombers hovering about in the sky waiting for someone to give them a fare. When called for they pounced immediately on their prey. This co-operation worked excellently, and dive bombing proved nearly as quick as shell-fire.

A bridgehead across the Rapido was forced, but it was a little precarious and barely a thousand yards deep. The country on the, other bank was a mass of minor features and visibility was seldom more than five hundred yards and often considerably less. It was perfect country from the Germans’ point of view. A tributary of the Rapido called the Pioppeto ran in from the west near the brigade’s concentration area. Its bend to the north-east just before joining the Rapido entailed a bridging operation.

The London Irish crossed the Rapido by a bridge built by the sappers and dug in. Getting fighting vehicles and heavy weapons up was difficult owing to the state of the tracks, and many trucks and anti-tank guns had to be man-handled. The attack by the Irish Brigade began next morning. The Inniskillings and the 16/5 Lancers smashed their way a thousand yards into the Gustav Line. That was “Operation Grafton,” and the London Irish Rifles were to give the next punch, “Operation Pytchley,” which embraced a ridge between Sinagoga and Colle Monache. The third bound, “Operation Fernie,” was on a ridge dominating Highway Six itself, and that was the job of the Royal Irish Fusiliers.

After “Grafton” had been carried through successfully by the Skins, the London Irish while in their forming-up area came under heavy fire, which was also directed at the tanks of the 16/5 Lancers, their partners in the attack. Lieut-Colonel Ian Goff was wounded and died shortly afterwards, and there were about forty other casualties, including Major Geoffrey Phillips, and Lieutenant Ken Lovatt, the signals officer.

Losing their Commanding Officer at the commencement of what was likely to be one of their toughest battles was a great blow to the battalion. Lieut.-Colonel Goff throughout the previous few months had handled the battalion with tremendous skill and energy. He had imparted much of his own personal ability and bravery to the men he commanded, and his loss was a sad one. It reflected the greatest credit on the 2nd Battalion that in spite of losing their trusted leader on the eve of a vital battle, it in no way detracted from the magnificent fight they put up. Lieut-Colonel Goff never doubted it would have been otherwise.

Major (later Lieut.-Colonel) Coldwell-Horsfall assumed command, but owing to the very heavy shelling and the approach of darkness which would have made consolidation difficult, “Operation Pytchley” was postponed until dawn next day, when it would be combined with an attack by the Lancashire Fusiliers on the right. The London Irish planned to attack astride the road to Sinagoga, with a troop of tanks in support of each company, and with Pioneers following up to de-mine the road for the reserve tanks and the rest.

ATTACK ON SINAGOGA

The battle began at 0900 hours, and the artillery salvos came down with a crash that made coherent thinking almost impossible. ‘G’ and ‘E’ Companies were held up for a while by heavy fire from Germans concealed in the cellars of houses. But the teamwork with the gunners was excellent, and many Germans were trapped in their dug-outs by the shell-fire and the riflemen went among them with the bayonet before they realised that the artillery barrage had passed on. In other places where the advance was delayed, the enemy posts were blasted to bits by high-explosive from the seventy-fives of the Lancers. Many anti-tank gun crews were caught away from their guns by the barrage, and the Germans realised that fact when it was too late and were then unable to man them. Others, when they opened fire on the tanks, were shot down by the infantry.

One of the main sources of trouble was the left flank across the Piopetto, which was entirely open, and throughout the battle the London Irish were under consistent and heavy fire from machine guns, mortars, and tanks. The Lancers helped considerably by giving more than they got and by setting fire to several AFVs, as well as blowing up two ammunition dumps. H Company, under Major Desmond Woods, eventually broke into the village of Sinagoga, where ferocious close fighting developed. This went on for over an hour, the Germans stubbornly defending the buildings with grenades, machine-guns, and Schmeissers. There was also a self-propelled seventy-five behind one of the houses which “sniped” at the supporting tanks. Corporal JA Barnes led his section in an attack on this gun. He went forward alone, covered by his Bren gunner, and in face of intense fire killed one of the gun-crew with a grenade before he himself was killed, a most gallant act.

Shortly after this, the garrison of the village started to surrender and by noon the whole of the objective was in the hands of the London Irish and the Lancers. ‘G’ Company, in the meantime, was having a stiff battle with a local counter-attack, but after about an hour this was cleared up. ‘H’ Company on the left pushed on and seized a group of houses overlooking the river. This proved to be most valuable in neutralising the counter-attack that came in from that side.

During the afternoon, the attack developed with all manner of fire going both ways, but it never really progressed and finally fizzled out. The casualties of the London Irish in the attack were five officers and sixty other ranks. Lieutenant Mike Clark, MC, who was killed, was a very sad loss, as were Sergeant E Mayo, MM, and CSM F Wakefield. At least one hundred Germans were killed and one hundred and twenty captured.

MAJOR DAVIES, OC ‘E’ COMPANY REMEMBERS

Written in 1978 to John Horsfall:

“In the afternoon of 14th May 1944, the Battalion crossed the Rapido (Gari) River by a Bailey Bridge put up by the 8th Indian Division. N Mosley, J Bruckmann and D. Fay were the ‘E’ Company commanders. I remember Sergeant Mayo MM and Sergeant McNally as two of the Platoon Sergeants with CSM George Charnick. The crossing of the river was quiet and I can remember no shelling. We spent a quiet night just inside the bridgehead.

Next day, the Battalion “O” Group moved to an area called “Happy Valley”. Here there was some shelling and Geoffrey Phillips, who was in command of ‘G’ Coy was hit in the head, but not badly. Peter Grennell took over as OC, ‘G’ Company. At about this time, the Commanding Officer, Colonel Goff, was killed by shell fire as was the Officer Commanding the 16/5 Lancers (Colonel Loveday). The battalion was to attack with the Lancers. Bala Bredin was immediately on the scene. I think that he was with the ‘Skins’ and I rather think that, following Colonel Goff’s death, he gave orders to the LIR for the attack on the next day.

In any event, ‘E’ Company moved into the area from which it was to attack Sinagoga wood, a feature about 2000 yards ahead. We were shelled when we arrived at the starting point. Mosley was hit and so, I think was Bruckmann. Most of the night was fairly quiet, save for the noise of the tank tracks which we hoped were ours and not theirs. We then had a splendid breakfast supplied by CQMS O’Sullivan.

The attack began at 0920 hours, preceded by very heavy artillery fire which began at 0900 hours. We went forward with a troop of 16/5 Lancers. The initial advance was through a cornfield, and the corn was quite golden and very tall and it was shame to see tanks mow it down. On the other hand, the corn afforded useful cover to the infantry.

Due to the noise of our artillery and tanks we did not realise that we came under heavy fire until we saw the odd man fall. I remember seeing Lance Sergeant Williams, a young soldier who had come from the 70th Battalion fall at this point. We were able to approach the wood under the protection of our own artillery fire, which was very accurate. I had an air photograph and this was of the greatest help in enabling us to take advantage of our fire plan.

I remember trying to communicate with the tank troop commander by using the telephone on the outside of his Sherman tank. Of course, the thing would not work. But the tank commander obligingly opened his turret when I hammered on it with a rifle. I showed him where I supposed some German fire was coming from. The Company was at that time using what cover there was, about 100-200 yards from the wood.

With the ending of the barrage, I realised that the Company had to go forward. I got up hoping that those near to me would do so too. Every man did so and we ran for the wood which we reached despite about a dozen casualties. In the wood, we took 60 prisoners of the 90th (PG) Division, and then I walked through the wood to find ‘G’ Company on our right had kept up with us.

In the wood, there was a small farmhouse which I took to be Sinagoga Farm. I went in and in a bedroom on the ground floor, there was a very old man and his wife. They were unhurt, and I tried to comfort them. I returned to the Company’s position in the wood just as a dreadful Nebelwerfer stonk arrived. This killed two of the best men in the Company: Sergeant Mayo MM and Corporal O’Reilly. The men of Mayo’s platoon buried him there and then. Before we moved on the next day, they had put a cross over his grave. On the cross were the words, “Sergeant E Mayo. The finest sergeant that ever breathed.” This, I saw myself.