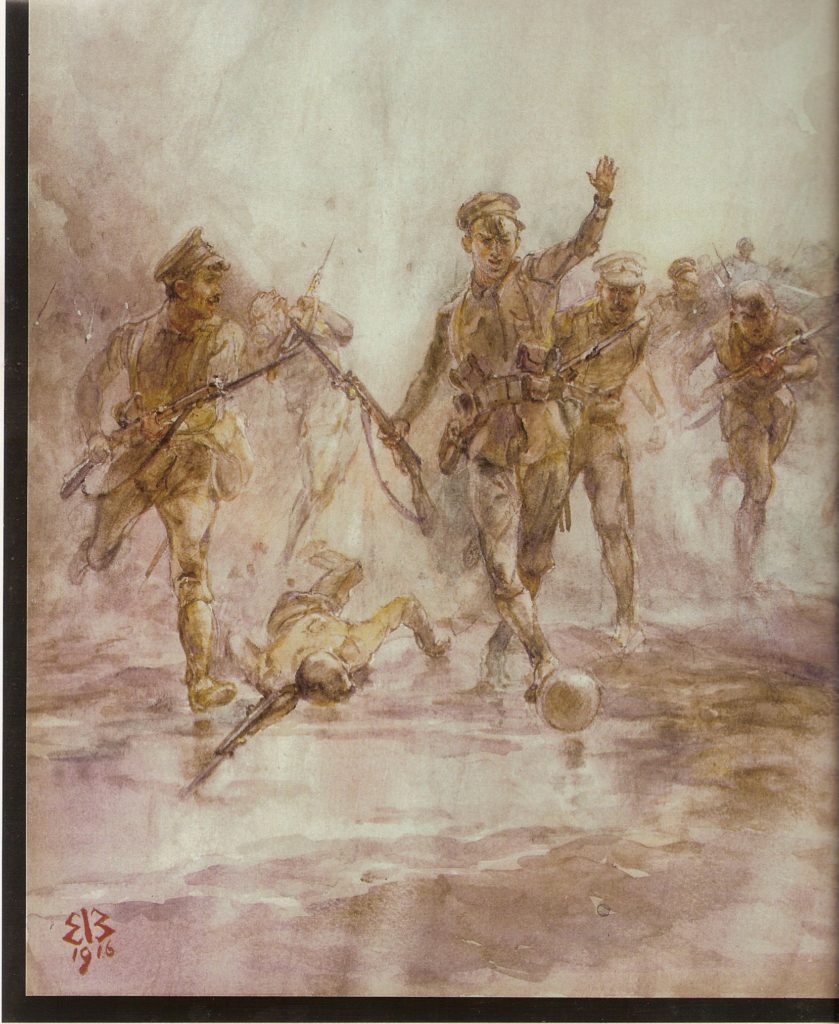

When examining the various artwork and historical artefacts within our Regimental museum, your gaze cannot fail to alight on an evocative watercolour painting that depicts a group of London Irish Riflemen, led by Frank Edwards, kicking a football across the trench line at Loos in September 1915. Astute observers will question the fact that none of the men appear to be wearing gas masks but it is certainly a most striking image of which we are most justly proud to hold within our collection.

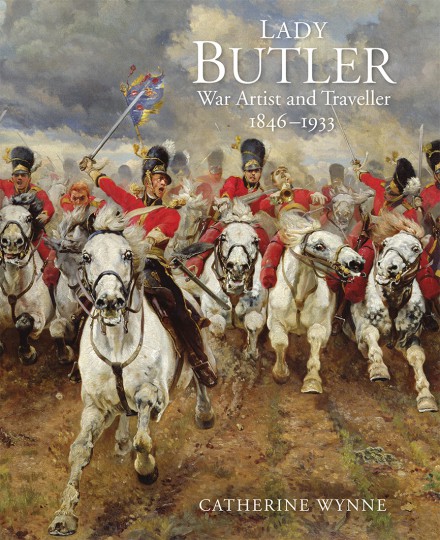

Perhaps less well known is that the name of the artist is Lady Elizabeth Butler, the subject of a recently published biography written by Dr Catherine Wynne. It is remarkable to learn that at the height of Lady Butler’s popularity during the 1870s, policemen would have to be stationed to manage crowds at the exhibition of one of her most celebrated paintings at The Royal Academy. The book is of course a detailed study of the rich tapestry of Lady Butler’s art but also provides an insight into some of the societal and political flows during the second half of the 19th century and the first part of the last. Beautifully mounted and the art images exquisitely reproduced, even without detailed prior knowledge of the subject matter, the book is a highly accessible and engaging read.

In 1874, Elizabeth Thompson had first come to national prominence after her painting “Calling the Roll after an Engagement, Crimea (The Roll Call)” was displayed at the Royal Academy. The painting is a remarkable study of wounded and war weary Grenadier Guardsmen gathering for a post battle roll call. As a result of that showing. Elizabeth became the talk of fashionable society and the painting was taken to Buckingham Palace for Queen Victoria to “gaze at”.

It was a massive breakthrough into the almost exclusively male dominated world of war art. A feature of Elizabeth Thompson’s work over the succeeding years were compassionate studies of the traumatic effects of conflict, depicting scenes from the Napoleonic and Crimean wars, images of which many of us will be familiar with. Three to mention in this respect are: “The 28th Regiment at Quatre Bras”, “Balaclava” and “The Return from Inkerman”.

In 1878, Elizabeth married Lieutenant General Sir William Butler and her first painting as Lady Butler was “Listed for the Connaught Rangers: Recruiting in Ireland”, a fantastically executed painting that has socio-political connotations. This was followed by “Remnants of an Army Jellalabad, January 13th 1842”, which was displayed while Britain was at war in Afghanistan, one of a series of imperial wars during this period. While her husband was posted to South Africa, Lady Butler showed her latest painting “The defence of Rorke’s Drift, January 1879” to both Queen Victoria and Prime Minister Disraeli, and this was followed in 1881 by the highly dramatic and feted “Scotland for Ever!” which celebrated the Scots Greys’ role in the victory at Waterloo.

By the early 1880s, Lady Butler had enjoyed a period of extraordinary success but it seemed clear that the public now wanted a more glorified view of empire building, which led to some personal discomfiture. To add to these frustrations, even after a number of well-regarded paintings since her marriage, she was still widely referred to as ‘Elizabeth Thompson’ and closely defined by “The Roll Call”.

In 1885, Elizabeth joined William in Egypt, before moving to France, and then to Ireland – and this latter period included the completion of one of her more pointed political paintings, “Evicted”, which was completed in 1890. Over the following years, her output tended to move from explicit imperial themes towards the depiction of historical battles. In early 1899, Lady Butler travelled to South Africa to join her husband, who had been appointed there as Commander of British Forces but he was to leave that position in August before the outbreak of the Boer War – he would later be unjustly criticised by elements of the “pro war” press.

In 1905, following Sir William Butler’s retirement from the army, the couple moved with their family to Bansha Castle in Tipperary near to William’s ancestral home – and Elizabeth would most definitely now become completely isolated from the London centric art world.

Following the outbreak of war in 1914, Lady Butler continued her work on military themes including exhibiting a series of watercolours of men who had been awarded the Victoria Cross.

The depiction of the ‘Footballers at Loos’ was shown alongside other war scenes at the ‘Khaki’ exhibition at the Leicester Galleries in May 1917 with all proceeds going to the Officers’ Families Fund. By the time Lady Butler came to look at the exploits of Frank Edwards and his comrades, it was certainly true that she had long since fallen out of favour with the cognoscenti but Catherine Wynne notes that, “throughout her career, her loyalty to the ordinary soldier remained steadfast.”

At the end of the war, Lady Butler remained in Ireland and would come face to face with the evolving political realities across the country. She continued with her work, which included the “Charge of the Egyptian Camel Corps”, badly damaged in fighting at Bansha during the Civil War, “The Retreat from Mons: The Royal Horse Guards” in 1927 and “A Detachment of Cavalry in Flanders” in 1929.

Elizabeth Butler died at the age of 86 in October 1933. A remarkable life indeed and, after absorbing her fascinating story and re-viewing her fantastically moving artwork, I do indeed share Catherine Wynne’s comment that Lady Butler’s life should most certainly be celebrated.

The book is available from Four Courts Press and is highly recommended.

RWOS, June 2019.

Reproduced from ‘The Emerald’.