Embarkation.

After an uneventful journey, the trains arrived at Southampton Dockside at approximately 12 noon and 230pm on 9th March. The scenes at the dockside were of bustling activity as the transports were loaded with guns and stores and the troops watched the work with considerable interest. Apart from one or two fatigue parties there was little for the troops to do.

It was, for some, a time of speculation as to the future; for others, the material consideration was how and where to get to get the last drink of honest English beer. Old soldiers like QM Sgt John Dillon, Sgt Bob Cunningham and Sgt Harry Tyers found a way.

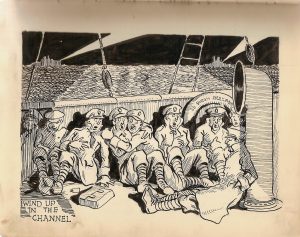

For most of the troops, there was nothing for it but to fill in several hours by walking round the dockside sheds or, by sitting on their kits, digesting Lord Kitchener’s letter of commendation and advice to departing troops or visiting comrades in the 17th and 20th Battalions, who were also present. About 9pm, the embarkation of the Battalion commenced. The strength of the Battalion comprised 29 Officers and 1048 other ranks. 538 men were accommodated on the SS Queen Alexandra, five Officers and 250 other ranks in SS Viper and the remaining Officers, the Transport and 200 other ranks in SS Trelford Hall, which sailed at 6pm, the Queen Alexandra at 8pm and Viper at 10pm. On board, life belts were served out, duties assigned and rations issued. During the journey across the Channel, destroyers circled round the transports but no one seriously thought that enemy submarines constituted a menace.

After exploring the vessels, the troops settled down for the night in the most comfortable places that could be found. By 4am the next morning (the 10th), the Transports were safe in the harbour at Le Havre. While awaiting disembarkation, the men enjoyed a good wash and shave and had plenty of time to study the landscape. Disembarkation proceeded smoothly from 8am onwards and was accomplished without incident, except for a little objection on the part of the Transport Section’s mules.

Arrival in Le Havre and Transit Encampment.

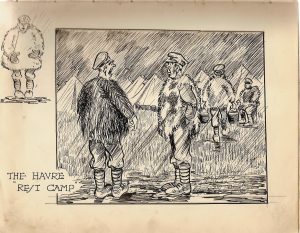

At 930am on 10th March, the Battalion formed up on the quay and marched through the town with bugles blowing and pipes playing. The French populace greeted the troops with smiles and cheers, which were returned with interest by the men. After a 5 mile march, the Battalion arrived at No 2 Camp and underwent an immediate food and kit inspection. A searching wind swept across the cliffs in which the camp was situated, and waiting barefooted for a protracted inspection after a 5 mile climb in full marching order was rather a trial and was also something in the nature of an anti-climax.

An area was assigned to the Battalion and, very soon tents, were pitched.

Warm comforts – in other words goat or sheepskin coats were issued. These were short armless furry coats, either treated or untreated in such a way to make them extremely malodorous. The coats provoked great merriment and the troops very comical as they capered about in imitation of ‘teddy’ bears.

In Camp, there were many “Mons” men and harrowing and gruesome stories were told. At night, the troops turned in with three distinct impressions:

– The retreat from Mons must have been pretty ghastly.

– French beer was too thin to be enjoyed, and

– That with fourteen men per tent, smelly fur coats were better left outside.

The night was a trying one for the Transport section – they were called out in the wet to deal with a stampede of horse and mules belonging to an adjoining unit. When order was regained, the Battalion was one or two mules “up” in its proper establishment. One can always learn a lesson and the opportunity was taken to get rid of “bad mules” and replace them quietly during the stampede.

The Slow Journey to the Front.

On 11th March, after a breakfast of bully beef, biscuits and water, the Battalion paraded at 745am. less 2 Lt Rich and 48 other ranks, who were sent to No 19 Camp at Harfleur as first reinforcements. The Battalion matched to the Railway Station, arriving at about 830am. Waiting in the Station yard were trains composed of enclosed trucks. It was a shock to the men to find that it was quite immaterial whether the party to be conveyed comprised men or horses. The same accommodating vehicles would serve in either case. If men, forty per truck could be carried; if horses, the same truck could take eight. Entrainment was satisfactorily completed by 11 o’clock with the troops packed like sardines.

Without any indication of its intention, the train began to move forward, Captain Hamilton, the Adjutant, engrossed in his duties, suddenly found himself being left behind, As the train gathered speed, he was forced to sprint for it. Fortunately, he was able to catch up and was safely hauled aboard.

All day long, the train pursued its leisurely course, passing through countryside not unlike that at home. All the trucks of the train had large sliding doors at the sides and the troops kept these wide open. Men nearest to the openings sat on the floor of the trucks with their legs dangling outside. The remainder crowded as near to the openings as possible, anxious to miss none of the scenes through which they were passing. All along the train’s length, choruses rang out and the challenging enquiry, “Are we downhearted?” was answered by yells of “No!”, which reverberated from truck to truck.

Bridges along the line were guarded and the track patrolled by French Territorials. The troops observed with interest how unlike themselves were the French Territorials. The British were young for the most part, men nearing their forties being few and far between. The French Territorials were almost invariably men past their prime and it is difficult to say whether their beards, bearing or uniform provoked most comment. Friendly greetings were exchanged between the troops and French folk stopped their work in the fields to wave their good wishes. Children by the wayside were vociferous in their demands for “souvenirs” of bully beef and biscuits. As the train was routed via Rouen, the troops were able to get a view of the Cathedral and to recall memories of Joan of Arc and her tragic fate.

At 530pm, the train stopped at Monterolier, near Buchy, and the weary troops were given a chance to stretch their legs and to wash. Tea and coffee, strengthened with rum, had been provided. For some, it was their first experience of rum in tea and coffee and many bitter remarks were made about the undrinkable quality of the beverages in consequence. It’s only fair to say that the reverse view was taken by others.

After a short halt, a warning blast on the whistle was given and the men again trudged back into the train. As evening wore on, the chilly atmosphere compelled the troops to close the doors of the truck. As there were no lights, attempts were made to settle down. The best that could be done was to pile up equipment to gain floor space but this was not a great success and no considerable degree of comfort was obtained. In consequence of the cramped conditions, very few men were able to snatch any sleep.

Abbeville was reached between midnight and 1am on 12th March. Again, the troops welcomed a stretch and a chance to take tea. By the flickering light of lanterns and the fires, which blazed merrily under a row of steaming cauldrons, mess tins were filled. Revived and warmed by the hot tea, the men soon worked off their stiffness. After a brief halt, the Battalion re-entrained and continued their journey through the remainder of the night.

When day dawned fresh and clear, the troops flung wide the truck doors. The train was now passing through a different countryside. Here and there, woods and villages on rising ground could be seen but, for the most part, the countryside was flat, dotted by hamlets and intersected by clean cut waterways. The fields were subdivided by wide ditches, clearly indicating a well organised irrigation system. The train passed through St Omer and, later at 930am, Bavinchove was reached. This place, a village situated a mile and a half south west of Cassel, saw the end of the train journey and de-training began without delay. Soon, fatigues parties were busy loading transport wagons with fodder and rations.

Marching to Billets and the Sound of War.

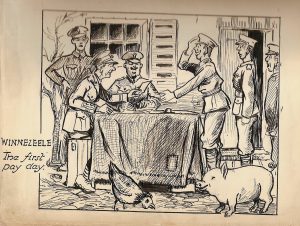

Duties completed, the Battalion formed up and marched off in brilliant sunshine to Winnezeele via Oxelaere, skirting Cassel in the south and east. The march was only six miles but it was very trying. The troops were tired and stiff after their long train journey, the weather was very hot and marching up and down the precipitous roads round Cassel, in new boots on pave roads, was a severe test of the Battalion’s fitness.

The route of the march was circuitous and it was rumoured that the men were marched miles out of their way so that they might pass the chateau headquarters of the local General. To ease matters, the troops took advantage of 10 minute halts to discard a good deal of their superfluous kit. Shirts, socks and hairbrushes and books were thrown away according to the urgency of the need to unburden which was felt by individuals.

Prior to reaching Winnezeele, “D” Company disengaged and billeted there. “C” Company broke off a little later and were billeted at Le Temple. The remainder of the Battalion continued the march and were accommodated in Winnezeele and district. The men were billeted in barns and slept on straw covered ground or in lofts. The barns occupied were usually attached to farmhouses.

A typical farmhouse comprised the dwelling and outbuildings, all rather dilapidated, arranged round a central square. The square was invariably an immense, evil smelling heap of manure in which pigs foraged with happy zest and chickens and ducks squabbled noisily for scraps extracted from the manure heap. The troops, well tutored in military sanitation, were inclined to be extremely scornful, not realising that the accumulated filth represented a solid wealth to the farmer and possibly the difference between good and bad crops.

One of “A” Company’s billets was positively loathsome, consisting of a huge loft, floored with filthy straw and with cow byres below. Access to the loft was obtained by means of a rickety ladder, set on the edge of a particularly foul midden. In daylight, the ladder could, with care, be negotiated with safety but in darkness it was definitely hazardous. One night, QM Sgt Dillon, returning from duty, or possibly leisure in Winnezeele, failed to observe that two rungs of the ladder were missing. Dire were the consequences of his attempt to tread on a rung which was not there. John fell down the ladder backwards into the midden with a yell and a splash. When rescued, poor John was in such a state as to be obnoxious to his comrades. A weak sense of smell only was needed to detect his presence from long range. Fortunately, it was possible for John to effect a rapid change of raiment, otherwise force of circumstances would have compelled his friends to remain aloof.

The next few days were spent in uneventful circumstances. The Battalion paraded daily for inspections, musketry, bayonet fighting practice and occasional route marches. Considerable importance appeared to be attached to the identify disc and iron ration, judging by the number of times it was necessary to produce them.

A roar of guns a few miles to the east gave a serious background to the Battalion’s work. A spy scare was rampant and the men were instructed to avoid going out singly and to carry a rifle and ammunition at all times. Some little excitement was caused one night when the Battalion HQ guard turned out and fired a shot or two across the fields but the occasion was not alarming. One or two farm employees, finding their way across the fields at night by lantern light were objects of suspicion and solemnly threatened with pains and penalties.

At every parade, by order of the GOC, findings of Court Martial and detail of punishments awarded were read out to the troops. The ‘shot at dawn’ element was so much emphasised as a warning that the men were irritated. It was at Winnezeele that the Battalion heard that La Bassee had fallen. It went on falling for about two years before the Battalion finally lost all interest in the place.

St Patrick’s Day, 17th March, was celebrated in proper style and, on that day, the Battalion was dismissed at 10am and paid five francs. Needless to say the estaminet ”Chapeau Rouge” did good business in the evening. On this day, orders were received for a move on the morrow and for the Transport Section to set out that evening. At 7pm, the Transport moved off with instructions to billet at Hazebrouk.

Moving Billets Again.

On 18th March, the battalion paraded at 630am ready to move off. The fur coats, which had been far from a blessing, were handed in to the great satisfaction of the troops. At 830am, the Battalion set out and marched a couple of miles in the direction of Cassel. At the halting point, 45 motor buses were waiting. These vehicles were London “Generals” painted black but, in many cases, bearing their destination boards – “Victoria” being much in evidence. The Battalion embussed and the procession began at 10am. In consequence of the heavy loading, the ride was somewhat bumpy. Once or twice, the buses were “ditched” and the “fares” had to assist in getting them back on the road. The buses followed a route via Hazebrouk to the road junction about three quarters of a mile south west of Morbecques. Here, the Battalion was dismounted and proceeded on foot to St Venant, arriving about 3pm. The march was approximately eight kilometres along a perfectly straight road and passing through the wonderful forest of Nieppe.

At St Venant, there was some little delay in getting the men settled into billets owing to the lack of a map of the billeting area but, eventually, all the men were accommodated satisfactorily – the majority being housed in large barns. The transport arrived at about 230pm with the horses rather tired after practically an all-night march. In the evening, the men cooked their food for the morrow and later explored St Venant. The town was one of fair size, offering shelter to a number of different units and providing adequate opportunities for refreshment of all sorts.

After a chilly night, the Battalion rose early and, emerging from billets, found the ground thickly covered with snow. Soon, the men were washing and shaving at the river’s edge with great flakes of snow whirling about them. One unfortunate individual, using the river as a shaving mirror, overbalanced and fell in. This Narcissus had, for his echo, the roar of ribald comment and unsympathetic laughter.

At 8am (19th March), the Battalion paraded and marched off in a blizzard via Busnes, Lillers, and along the Bethune Road turning to the right via Allouagne to Burbure, arriving at 215pm. During the whole march, which was of about fifteen kilometres, the weather was atrocious: snow, rain, hail, sleet and wind all being experienced. Fortunately, there were no hills to climb, otherwise the march would have been even more unpleasant. Other units of the Brigade were more fortunate and did the whole journey by bus.

At Burbure, the men were billeted comfortably and, for the most part, in good barns. Battalion Headquarters was established in the estaminet, “Bramley Blondel”, which the Battalion war diary describes as “very suitable”. The next few days were devoted to drill, training and inspections Work was carried out on the extensive village green and over a training area, which had been allotted to the Battalion.

Inspection and Training.

At 9am on 22nd March, the Battalion turned out as strong as possible on the village green to wait inspection by Field Marshal Sir John French. As the FM did not arrive until afternoon, the morning was occupied by practice bayonet fighting and musketry. At 230pm the Battalion was very closely inspected by Sir John and was highly praised for its smart appearance and soldierly bearing. The Commanding Officer, Colonel EG Concanon, was warmly congratulated on the general turnout.

The Adjutant, Captain AP Hamilton, was particularly pleased and informed the CO that he had never seen a regular Battalion put on a better show and that its bearing during the inspection indicated the highest state of efficiency.

For the remainder of the month, hard training continued. The first parade, usually under Company arrangements, took place at 750am, followed by the Battalion parade at 9am. With only a brief interlude for the midday meal, the work continued until late afternoon. Physical drill, musketry, bayonet fighting, extending order, close order drill, digging and route marches comprised the serious training while welcome visits were made weekly to the Mine No 4 Raimbert for baths. During this period, the weather was generally good. Very little was heard of the firing line a few miles away and, apart from the passage overhead of aircraft and an instruction to report the progress of a Zeppelin seen in the vicinity of Cassel, the war concerned the Battalion very little.

Preparation for Trench Warfare.

On 28th March, the CO, two other Officers and three NCOs visited the firing line at Neuve Chapelle for instruction in trench work, under the tuition of the 1st South Wales Borderers (1st Division) and parties of officers and NCOs followed daily, to make closer acquaintance with the trenches.

About this period, Company Commanders ascertained the names of men with cricketing ability and such individuals found themselves embryo Bombers. Lieut HU Mann took the first parade of the Bombers for throwing practice on the 30th March and, thus, came into existence the Battalion Bombers, whose subsequent exploits made them famous from the trenches to the base.

During the early days of April, it became definite that the Battalion would soon be in the firing line. The Medical Officer lectured on First Aid and field dressings. Company Commanders lectured on their experiences in the line. Lt Lytton lectured on the machine gun and snipers were selected and given special training.

Communicating with the Natives.

The Battalion enjoyed its stay in Burbure and, in spite of picquets charged with the duty of clearing the estaminets at 8pm nightly, the men had a good time. The inhabitants of the village were on good terms with the men and endeavoured to teach them sufficient of the language to permit purchases to be made in the shops. There were some amusing incidents arising out of purchases and Cpl Kingsley of the Transport Section once, when wanting a kilo of sausages, asking for a kilometre of that dainty. After his first shock of surprise, the shopkeeper laid out his entire stock on the counter in long rows. Placing his hand over the sausage in the manner of a fisherman describing his catch, the shopkeeper rattled out a succession of “combiens”, simultaneously enlarging the gap between his hands until he had indicated lengths of sausage ranging from a foot to well beyond the confines of the shop. Kingsley concluded that his French was slightly adrift and wisely amended his orders by gesture.

Nearly a fatality!

It was at Burbure that Sgt Cunningham of “A” Company was nearly killed by L-Cpl B……. “A” Company had furnished the Battalion guard, with Sgt Cunningham in charge. At reveille, after a night of guard duty, the sergeant paraded the men and gave the order: “for inspection, port arms”. Before proceeding to inspect, Sergeant Cunningham signalled to his L-Corporal that he did not wish to examine the NCO’s rifles. L-Cpl B…… promptly shut the bolt and pressed the trigger and Bang! …. off went one round of ball between the head of the Sergeant and the Lt-Corporal’s neighbour. The unfortunate NCO was promptly clapped under arrest. Later in the day, as the Orderly Officer of the day appeared to be late, Sgt Cunningham ordered his rifleman, acting as NCO, to see if the Orderly Officer was in the vicinity. The acting NCO took a walk round the village green and, failing to see the Orderly Officer and with visions of an irate Sergeant to contend with, thought he had better extend the field of his enquiries and called at the Commanding Officer’s billet. After politely knocking on the door, the acting NCO was admitted to the presence of Col Concanon. “Please Sir, Sgt Cunningham says he wants the Orderly Officer. Do you know where he is?” The Colonel, always considerate to his men, answered with a smile that he regretted that he could not assist. Thereupon, the acting NCO returned to the Sergeant and reported that he could not find the Orderly Officer and even the Colonel did not know where he could be found. Needless to say, Sgt Cunningham, on learning that the Colonel’s billet had been invaded, expressed himself so forcibly that the miserable acting L-Corporal, was left trembling like the proverbial aspen.

Moving near to and work at the Front.

At 1030am on 7th April, the Battalion paraded in full marching order on the Battalion parade ground and, after being inspected and addressed by the Brigadier, left for Bethune at 11am. The march was about 8 miles via Allouagne and Chocques and the General Officer Commanding 1st Corps inspected the Battalion en route. By 4pm, the men were billeted in the Girl’s Orphanage at Bethune with one Company quartered on each floor. The building was a commodious one, but with very little glass in the windows and bearing signs of having suffered from shrapnel.

On arrival, the CO and the Adjutant proceeded to HQ, 6th Infantry Brigade (2nd Division), the unit to which the Battalion had been attached and received detailed instructions for the following eight days, Briefly, the orders provided for one Company to remain in Bethune, one Company to proceed daily to the trenches as a working party; one Company to billet at Annequin to supply working parties as needed; and the remaining Company to proceed to the trenches with two platoons in the firing line and form part of the Support Line at Harley Street.

The Battalion was attached to No 1A (A1) sector situated north of the Bethune-La Bassee road around the village of Quinchy (Cuinchy). The Companies were to change over every forty eight hours and the platoons in the firing line to be relieved every forty eight hours. Thus, every platoon was to complete twenty four hours in the front line every eight days.

Under Fire for the First Time and Casualties.

On the following morning (8th April), “A” Company paraded at 715am and moved via Beuvry and Annequin to the trenches, leaving two platoons at Harley Street. “B” Company paraded at 730am and moved, via the same route to carry out digging under the supervision of the East Anglian RE. “C” Company paraded at 745am and followed the same route and reported to OC, 11th Field Company for work. “D” Company remained in Bethune.

The march to the line was not without incident. In the cold weather, and with occasional hail storms, the Companies set off in the highest spirits in column of route. On approaching the line, the troops moved with an interval between platoons and later in single file on each side of the road. En route, there were many signs of war. The countryside appeared to be desolate and many shell battered houses were passed. Several soldiers’ graves were seen, each with its neat wooden cross and inscription. Here and there, groups of soldiers played football beyond the poplar lined road and parties of cheerful French troops marched nonchalantly down the centre of the road. Suddenly, the whine of a shell was heard, followed by two more. With a roar, the first shell exploded in the road and two men of “B” Company were hit. Other shells exploded above the tree tops and shrapnel be-spattered the road, fortunately without causing casualties. Shelling continued for some time but the men, under fire for the first time, behaved well and even looked at the exploding shells with amusement. At Harley Street, “A” Company were fitted out with thigh boots and proceeded along a communication trench towards the line, keeping their heads well down as instructed, After proceeding in a crouching positon for what appeared to be the best part of a mile, the men were astonished to see men of the RE working and walking about in the open. Apparently, making new troops keep their heads down unnecessarily was an old soldiers’ joke.

Continuing the journey, No 3 and 4 Platoons eventually reached the front line, which was held by the 1st KR Rifles. The men were quickly posted as sentries and allocated duties. The firing line was about 150 yards from the German front line and was a trench about 6 foot 6 inches deep, buttressed, traversed and fire-stepped and ran in front of a number of brick stacks. The parapet was heightened with sandbags and steel loopholes were built at intervals, through which the parapet of the enemy front line could be discerned beyond a maze of barbed wire entanglements. There were a few enemy dead lying in no-man’s land and had obviously been there some time.

A party of London Irish was detailed to extend a sap, which ran out of the front line. The men set to work with pick and shovel but the enemy soon observed the earth being thrown over the side of the sap and amused themselves by firing as each shovelful of earth was thrown out of the trench. Later, during the morning, the enemy shelled the line with “pip squeaks” (small calibre, high velocity shells) and with shrapnel.

As the bombardment was heavier than usual, a “stand to” was ordered, in case the shelling was a prelude to an assault. The shelling gradually slackened off and the word to “stand down” was given and work resumed.

The support platoons of “A” Company, quartered in ruined houses at Cambrin, were detailed to clear a communication trench of an accumulation of mud and water. Returning from their task, the party passed through the ruins of what once was a stately residence. The green and slimy pool in the courtyard had once been an ornamental pond and the courtyard itself was littered with broken roof tiles, bricks, rafters, beds, wardrobes, chandeliers and quantities of other ruined building materials and household effects.

At dusk, “stand to” was ordered and standing alongside men of the KR Rifles, the London Irish were initiated into trench routine and the ways of the enemy by these well trained regulars. An hour later, at “stand down”, the work of the night commenced. Sentries were instructed to stand on the fire step and keep a good lookout and patrols and working parties set about their duties. The night was very dark but the star shells, fired at intervals by both sides of the line, revealed the stark detail of no-man’s land, as they described their firing parabolas of dazzling light.

Although there was a good deal of rifle fire, nothing of note occurred during the night and, at 9am the next morning, No 1 and 2 Platoons relieved No 3 and 4 platoons, who then returned to Cambrin in support. While No 3 and 4 Platoons had been receiving their instructions in trench routine from the KR Rifles, No 1 and 2 Platoons had been occupied filling sandbags to block up the windows of the houses in Cambrin and in constructing a barricade across the Bethune-La Bassee road.

On 10th April, “A” Company returned to Bethune, having been relieved by “B” Company. “C” Company relieved “D” Company at Anenquin and “D” Company proceeded to work under the direction of the RE. At 4am in the morning, the French, occupying the sector on the right, shelled the enemy and then blew a mine under the German front line, 200 yards south of the La Bassee road. The mine exploded with an earth shaking roar and a vast sheet of flame leapt skywards. In an instant, coloured rockets and star shells were shot up by the enemy infantry. The German artillery promptly responded to the SOS Signals and shells were soon shrieking and crashing in to the trenches with shrapnel bursting overhead. Machine guns and rifles sprayed the parapet with bullets, while the troops on the flanks stood to arms ready for emergencies. For “B” Company, it was an alarming experience but, fortunately and surprisingly, no casualties were suffered. “C” Company took over the line on 12th April and had two men wounded.

On 13th April, orders were received for the Battalion to take over a position of the adjoining Sector (A2) from the 5th Battalion, Liverpool Regiment (T). The Battalion (less “D” Company, who were in Sector A1 with the South Staffords) accordingly moved up via Beuvry and Annequin to Cambrin where “A” Company went into the firing line with “B” Company in support at the Quinchy strong point. The portion of the line occupied by “A” Company comprised shallow trenches with high breastworks in the Quinchy Brickstacks.

The Brickstacks were vantage points of snipers and were, in consequence, severely shelled and bombed by enemy trench mortars. The support platoons were chiefly concerned with the provision of listening post garrisons and ration parties, while No 4 platoon, “A” Company, provided reliefs on the mine air pumps. The listening post was established at the end of a long sap, which ran so close to the enemy line that, at night, Germans could be heard talking and working in their trenches. After a fairly quiet night, there was some heavy shelling by the enemy of the ground, about 200 yards west of Quinchy in retaliation for registering activity by our artillery.

Some Relief from Line Duties and Diversions.

Between 330 and 430pm, the Battalion was relieved by the 20th Battalion, London Regiment (“D” Company was relieved in A1 Sector at 12 noon) and, by 630pm, the whole Battalion was concentrated in the Orphanage, Bethune. The next few days were spent in fine weather, carrying out Company training, drill route marching and bathing. The first baths at Bethune were provided in the courtyard of the Orphanage by Pioneer Sgt Clark, whose minions hurled buckets of water over the men as they passed naked in single file.

About this time, a rumour spread throughout the Battalion that the CO had given orders for the rum ration to be poured down the drains. Although the majority of the men were completely indifferent to the fate of the rum, some of the older men quoted military law and stated the penalties alleged to be prescribed therein for wilful destruction of Government property. No one seemed to have any definite information on the subject and probably the only reason for the rumour was the absence of a rum ration.

Full advantage was taken of the stay in Bethune to get and provide amusement. The Battalion gave a very successful concert on 16th April and there was also a certain amount of boxing and football. On 17th April, the Battalion football team beat Regular Cyclists by three goals to nil.

On 19th April, in accordance with orders, the Battalion set out for Gorre at 1115am to take over from the Worcesters, with a view to relieving the Highland light Infantry in the C2 Sector on 23rd April. The march to Gorre was an easy one of four and a half miles and, in a short time, the Battalion reached its destination. Gorre was found to be a pretty village situated in the banks of the Aire – La Bassee canal. Billets were clean, comfortable barns, with a background of woods, thickly carpeted with primroses and wild anemones and the singing of nightingales could be heard frequently. In close proximity to the billets was a shell damaged chateau used as a canteen and this was much patronised by the men.

In the afternoon, instructions were received at Battalion HQ at Loisne for two parties of 100 men each to be paraded for work in the line. The first party paraded at 645pm, drew spades and proceeded to the rear of the line, via Festubert, for trench digging. The night was pitch black and star shells from the line provided the only illumination. Satisfactory progress was made on the task and, at 1130pm, the second party arrived to take over. For the next three days, similar working parties journeyed to the line and, although the digging was carried out in the open and the ground exposed to some rifle fire, the only casualties sustained were two men wounded.

The weather continued fine and training was carried out daily in ideal conditions. There was a good deal of bathing in the canal although the water was rather cold. On 20th April, the Battalion football team played the RE winning by 4 goals to nil but lost to 16th Battery RFA by 2 goals to 1 on 21st April.

Spy Fever.

Owing to repeated warnings on the subject of spies supposed to abound behind the line, everybody was alert to suspicious characters. An artillery man reported to Sgt Harry Tyers, that a man dressed as a French soldier, took great interest in the guns and was usually loitering in a field adjacent to the gun pits. Sgt Tyers collected a few men and, armed with a revolver, set out to capture the suspect. On sighting his man, the Sergeant sent two of his men to the right and two to the left and himself went straight ahead.

The Frenchman, fearing trouble, at once made off and the faster the pursuing party went, the faster the Frenchman moved. Tyers and his men broke into a trot and their quarry took to his heels and ran for it. Then followed a pretty chase over hedges and ditches, through fields, over barbed wire and a stream until, very much blown, the hunted man found sanctuary with a party of French soldiers engaged in road mending. He made straight for the officer in charge, jabbering and gesticulating frantically.

Tyers and his party, flushed with the chase, dashed up to seize the victim but were very much rebuffed to find that the “spy” was merely one of the road mending gang who liked to see the guns fired. The French officer did his best, but he paid for a lot of vin rouge before finally smoothing out the ruffled feelings of Tyers and his party.

Holding the line independently at Givenchy.

Owing to the wet and low lying nature of the ground, the front line consisted of a series of sandbags butts placed at intervals of about three foot six inches high to serve as a screen for movement. Most of the butts provided a firing point and shelter from the weather for about six men. The garrison of the posts were expected to remain concealed during the hours of daylight, being visited periodically by an NCO.

The enemy line was about 150 yards distant and a ditch and a line of willows and plenty of barbed wire intervened. The HLI had left the butts in excellent condition and, to add to the comfort of the incoming troops, handed over lighted braziers complete with supplies of fuel. In some cases, they had heated up Machonochie rations for the delectation of their relief. The Machonochie ration, hitherto unknown to the Battalion, consisted of a generous sized tin containing cooked meat and vegetables only needing warming up to provide a really substantial meal.

Preparations for Gas Attack.

Throughout the line, news of the enemy gas attack had circulated and, for the protection against gas, the men were provided with pads of cotton wool enclosed in gauze. These pads were soaked in a solution of carbonate of soda and were designed to be fitted over the nose and mouth, four strings or tapes being attached for secure fitting. The pads were only effectual when wet and the men were told that, in emergency, human urine was to be used to damp the pads.

Enemy Communications.

The attitude of the enemy was not aggressive, there was a little shelling in the mornings and evenings but little active hostility. At one point, on the German road barricade, could be seen a board inscribed “We are Saxons, you are Anglo Saxons. Save your bullets for the Prussians.” Frequently, the Germans shouted greetings and sang cheerily. They yelled, “we don’t want your fireworks” and enquired as to the state of London and for news concerning the English Football Cup results. After ringing a bell, a leather lung-ed German bawled out the latest war news generally announcing wonderful victories over the Allied Forces.

Stretcher Bearing Sgt Pratt.

There was little activity by day but a good deal of bustle at night. The butts and the sandbag barricade constantly needed repair and raiding patrols explored no-man’s land where there we many Indian soldiers lying unburied, while ration and water parties toiled unceasingly. During the Battalion’s tour in the line, there were only two casualties, one man being wounded by shrapnel on the way up to the line and Sgt Pratt of “A” Company had his jaw smashed by a bullet. As the wounded sergeant was in bad state, it was necessary to get him to Hospital as quickly as possible.

He was a big, heavy man and three of “A” Company’s taller men, Rifleman Munday, Warren and another, undertook the task of getting him propped up on a stretcher and carried out of the line down a road pitted with shell holes and littered with debris from ruined houses. The Sergeant’s removal was carried out in daylight and, in spite of some sniping, the wounded man was delivered at the dressing station without further harm.

After the carrying party had remarked on the Sergeant’s extraordinary weight, it was discovered that a full case of bully beef had been used on the stretcher as a pillow!

Relief by the 20th Battalion.

On the following day (27th April), the Battalion was ordered to proceed to the line to relieve the 20th Battalion in the sector previously occupied in front of Festubert. To freshen up the troops, there was three quarters of an hour of arms drill in the morning and Sgt Major Instructor Foley gave the Battalion a very hot time. The Sgt Major was particularly exacting but, as he knew his job thoroughly and had a clear ringing and metallic voice, the Battalion always responded well and executed orders with enthusiasm and precision.

The 20th Battalion was relieved without incident at 1015pm and the Battalion settled down to the routine work of the line. “A” Company, established in Brewery post, some little distance in front of Festubert, provided carrying parties for the line. On the night of 28th April, every man of a large carrying party drew two tins of biscuits and set out for the line to stock an emergency ration dump. The journey was a hazardous one. A long line of men carrying two shiny new biscuit tins, from which the rays of a brilliant moon flashed in all directions, was conspicuous enough to be seen for miles. However, apart from a little sporadic sniping, the enemy chose to ignore the scintillating procession and the journey was accompanied without casualties – to the great surprise of all concerned.

Two men were wounded during the tour in the line, which concluded when the 20th Battalion took over on 29th April.

The First Fatalities.

The first fatality of the Battalion occurred on the night of 30th April when one man was shot in the stomach when on a working party in the line in the C2b section. At 830pm on 1st May, the leading Company of the Battalion reached C2 sector and took over from the 20th Battalion, relief being completed by 1015pm. During the night, a machine gun sentry was shot through the head and killed instantly. The roar of the guns further north was very plainly heard and the distant bombardment had the effect of exciting the troops of both sides. There was a considerable amount of rifle fire and, at intervals, the Germans could be heard shouting and singing. Patrols and working parties were very active. About midnight, a German suddenly appeared in front of one of “A” Company’s butts. The sentry and Cpl Gerard at once opened fire. The German, however, quickly disappeared in the darkness.

At daybreak, after a very cold night, normal conditions prevailed. During the day, a white flag was waved in the enemy trenches. It was quickly seen and, as the troops crowded to the parapet and looked over the breastwork, the enemy snipers opened fire. During the day, there were two casualties, one man killed and the other wounded.

The night of 2nd/3rd May was very cold and, again, there was considerable activity as both sides appeared to be rather jumpy. When dawn broke, the sentries had the satisfaction of seeing a German lying dead on the parapet. During the day (the 3rd), heavy gun fire was heard to the north and south and our artillery joined in and shelled the enemy line opposite the Battalion sector with shrapnel and Lyddite. The bombardment blew some breaches in the enemy breast works and the Germans were sniped at, as they repaired the damage. Two men of the Battalion were killed in the line on 4th May, prior to relief by 7th Battalion, London Regiment.