Out of Reserve and taking over in the Loos Salient.

After a night of heavy rain, the Battalion spent the next day (2nd December) marching back to Raimbert, departing at 9am and following the route: Mametz, Blessy, Auchy au Bois and Ferfay. On arrival at Raimbert, the old billets were reoccupied. The Battalion’s training concluded on 11th December. The Sergeants of the Battalion celebrated the end of the Corps Reserve period by a highly successful dinner and concert held in the largest estaminet in the village. The grenadier platoon maintained its reputation by winning the Brigade Bombing contest and, later, the Divisional Bombing competition.

On the night of December 11th, the men retired early in readiness for departure scheduled for the morrow. By 4am on 13th December, the Battalion was busy packing up. The London Irish had, as usual, established themselves in the affections of the villagers and practically the whole population turned out to see the Battalion march off. On arrival at Lillers, the Battalion entrained for Noeux-les-Mines and, from there, the Battalion marched to Labourse relieving units of the 46th Brigade (15th Division).

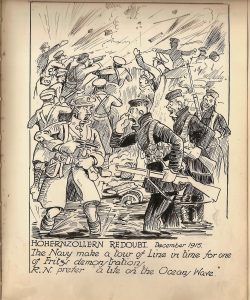

The 141st Brigade assumed command of the “C” Sector on 14th December, taking over from the Black Watch in the “Hairpin” and adjacent trenches. The Brigade sector was the northernmost portion of the Loos Salient and including within its limit the famous Hohenzollern Redoubt. The line was in a ruinous state with mud and water everywhere. But for the issue of gum boots, it would have been impossible to maintain a hold on the forward trenches.

Communication trenches, because of the glue like consistency of the mud, were almost impassable and, in the front line, the garrison had mud and water up to their knees to contend with day and night. The victims of the September massacre and the actions which followed were still, to a considerable extent, unburied and the whole atmosphere of the section of one of nauseating putrefaction and depressing in the extreme.

German aggression and commendation for our Bombers.

The Germans opposite were showing remarkable activity and asserted themselves to the point of superiority. This was particularly marked in regard to digging and bombing. The enemy could be seen digging well within the range of trench mortars and rifle grenades, while his machine guns sprayed our parapets at short range.

It was obvious that this contemptuous disregard of the opposing forces could not be tolerated by the 47th Division and, in consequence, orders calculated to bring the enemy to a sense of realities were issued. All ranks were urgently impressed with the necessity for the utmost activity with sniping, rifle grenades, machine gun fire, bombing, patrols and trench mortar fire. In addition to establishing and maintaining supremacy in this direction, the Corp Commander invited Battalion Commanders to consider the possibility of organising raids and enterprises at about one Company strength with the idea of securing identification of hostile units, inflicting casualties and destroying trenches, mine shafts and material.

At 9am on 15th December, following remarkable activity on the previous day, the enemy made a bombing attack on the London Irish barricade in Essex Trench. Rifle fire accounted for five Germans as they clambered over the barricade. A few of the enemy, who succeeded in getting into the section of trench between the British and German barricades, were easily disposed of by the Bombers. Bombing by the London Irish grenadiers was extremely accurate and so effective that the enemy attack was quickly smothered.

The enemy remained inactive until 7pm when, in the darkness, a German succeeded in crawling down Shipka Sap as far as our post. The German quietly raised himself and looked over the barricade. A bomb was hurled at him at once and he quickly disappeared in the darkness. The prevailing circumstances gave the impression that the attack would be resumed and a very sharp look out was kept. The Grenadier Officer, Lt Munro, moved his two Reserve Sections nearer the saps and a patrol was sent out at 8pm to investigate. The patrol reported that our bombing had caused considerable damage to the enemy barricade and that the enemy was quiet and not attempting to carry out repairs.

At 1145pm, a German officer suddenly appeared at the barricade in Shipka Sap and deliberately fired three shots from his revolver at the bombers. Simultaneously, a new bombing attack was launched. Well directed salvos of bombs were hurled by the enemy from the right flank of the sap as well as the front and the Bombers fell back slightly to avoid the first onslaught. The alarm was given and the reserve sections of the Bombers quickly moved forward.

With support and supplies of bombs at hand, the grenadiers immediately engaged the enemy. Rapid and accurate bombing quickly drove the Germans back over the barricade and the sustained bombing of the London Irish Bombers effectively prevented any further enemy advance. Well concealed German bombers on the right flank collaborated with the enemy in front and German bombs fell as far as forty yards down the sap.

To isolate the grenadiers, and to prevent reinforcement and supplies for being rushed forward, the enemy kept up a steady fire of rifle grenades but this miniature barrage was not successful and most of the rifle grenades burst harmlessly in no man’s land between Essex Trench and the front line. By the light of star shells and the flashes of exploding bombs, the German officer directing operations could be seen and the orders shouted to his attacking party could be plainly heard.

For three quarters of an hour, the bombing duel continued but against the uncompromising resistances of the London Irish Bombers, the enemy attack, although pressed vigorously, could make no progress. The intervention of the artillery, called for about twenty minutes after midnight, silenced the enemy and the rest of the night passed quietly.

At dawn on the 16th, to forestall any activity contemplated by the enemy, the Battalion grenadiers became aggressive and bombarded their adversaries’ barricade with bombs. The Germans were not in the mood to reply and receiving no encouragement to continue, the Bombers allowed the affair to die down.

The Corps Commander communicated a message to the Colonel offering his congratulations on the spirited and successful defence of the saps in the Hairpin against the enemy attack.

For their part in this action, the London Irish Bombers were specially commended by the Brigadier and Lt Munro was awarded the MC.

Relief by the 7th Battalion and the work of the Transport Section.

During the day (16th), the Battalion moved back into support and, on the 18th, were relieved by the 7th Battalion and marched back to Verquin. While in the line, the Battalion had a trying time but, whatever the circumstances, the Transport Section always managed to get forward with the rations. The nightly journeys to Lone Tree dump were fraught with considerable danger and great discomfort. The roads leading to the dump were subject to overhead machine gun fire and, at intervals, shrapnel fired from several directions burst on the tracks of the transport.

Lone Tree, the one outstanding feature in a dreary waste, was well known to the Germans and it was common knowledge that the enemy used it as an aiming mark for his artillery. After a time, the tree was cut down and, on very dark night, it was very difficult for the transport and ration parties to locate the dump. The ground in the vicinity was a quagmire. Four horses per wagon were often necessary owing to the mud being up to the horses’ bellies. The old trenches, which traversed the district, were made passable for the transport by the provision of wooden bridges. It was a difficult enough task to locate the bridges and a tremendous job to get the wheels, half buried in mud, over the bridge ends. The horses slipped on the greasy boards and man handling was nearly always necessary.

Men of the Transport will doubtless remember, too, the dud 15” shell, which lay across the road to Loos. In consequence of the enormous weight of the projectile, for a time it could not be moved and the Transport Officer was not, on this occasion, the only person to be relieved when the last wagon had safely bumped over the obstacle.

Christmas 1915 in the Hohenzollern Redoubt: Mines and Counter Mines.

The London Irish relieved the 23rd Battalion in the D2 sub-Section (Hohenzollern) on 23rd December. This sub-Section was, if anything, worse than the Hairpin sub-Section, which the Battalion had recently occupied. Communication trenches and the front line, which in some parts was merely a series of “T” pieces, were knee deep in icy water but worse than the water was the deep sticky mud. Information had been received of the possibility of the enemy springing a mine under the Hogsback and it was thought that the time fixed for the occasion was Christmas morning. In consequence of this intelligence, the GOC gave the order for the line to be more strongly held and for the Brigade Reserve and Brigade Machine Gun Company to be pushed forward.

Division intimated to Brigade at 530pm on 23rd December that, to anticipate the enemy, arrangements had been made to explode a counter mine under the Hogsback at 7am on 24th December. This information was communicated to OC, London Irish Rifles with instructions to make the necessary arrangements for evacuating the section of line affected and for securing the crater after the explosion of the mine. Colonel Tredennick had no time to prepare and issue written orders and, in consequence, the Company Commanders were called together and given verbal instructions.

Dispositions were as follows:

“A” Company (right Company, Captain P Maginn): holding the line from Poker Street to Bart’s Alley to withdraw about five traverses south east of Bart’s Alley. This Company was to be responsible for seizing the south and south east lip of the crater. For this purpose, two parties, each of eleven men under a NCO, were organised. One party, under Sgt Lawless, was posted at the junction of Bart’s Alley and the front line. This party, with a section of bombers attached, was required to seize the lip of the crater at this point. The second party, under Sgt Newton, was posted at the junction of Bart’s Alley with West Face. The duty of this party was to seize the west lip of the crater and to make contact with the party east of it.

“B” Company (left Company, Lt Topham): holding from Bart’s Alley to the junction of Mud Trench with OBI was withdrawn to the junction of Sticky Trench and Guildford Trench. At this point were placed two parties, each of eleven men under a NCO, preceded by a group of bombers. One party was to rush along the front line trench and seize the lip at the crater at that point, the other party, going down West Face, was to rush in behind the crater. A Lewis Gun was posted at the junction of Guildford and Sticky Trench to sweep the front of the crater from that direction. Another machine gun was placed south east of Bart’s Alley in the front line to sweep across the crater from the south east.

One Company was placed in Northampton Trench between Savile Row and Bart’s Alley. After the explosion, this Company was to prolong its left to cover the rear of the crater. One platoon occupied Northampton Trench, immediately in the rear of Sticky Trench, the remaining three platoons occupied OBI astride Bart’s Alley.

In addition, two Companies of the 20th Battalion occupied Railway Reserve and a section of Cyclist Bombers was posted in Northampton Trench near Bart’s Alley.

During the night of 23/24th December, the Grenadier Officer and Company Commanders detailed their parties and dispositions and all necessary steps were taken to ensure the success of the operation.

Brigade arranged an artillery programme and also for two sections of the 20th Battalion Bombers to be available to support the London Irish Bombers and to carry bombs from the Brigade bomb store to the Battalion bomb store in the Quarry.

After a wretched night, scrambling and splashing about in deep mud and water, the Battalion ‘stood to’ awaiting events.

Firing the Counter Mine.

At 718am on 24th December, the counter mine was fired. From below ground, came a growling rumble and the trenches rocked and swayed under the stupendous power of the exploding mine and counter mine. With a thunderous roar, the charge broke the surface of the ground and the centre section of the line was hurled high into the air. Simultaneously, a heavy artillery fire crashed down on the enemy line and the flank companies (“A” and “B”) opened a rapid fire to cover the advance and the Lewis guns played across the front of the mine.

After the initial surprise, the enemy guns and trench mortars came into action and the German infantry could be seen standing on their fire steps fixing bayonets, while reinforcements were observed rushing down a communication trench to the front line. The air was full of debris, which fell in clogging cascades over the whole area, plastering the men with filth and mud. The explosion formed a deep crater roughly 80 feet across, surrounded by a continuous lip of shifting and smoking earth.

As rapidly as possible, the assaulting parties moved forward with the Bombers in the van. Sgt Barrett, who had tossed with Sgt Penny for the privilege of leading “B” Company’s party and won, was quickly in position while the other “B” Company part succeeded likewise. Sgt Loveless of “A” Company and his party speedily reached his objective in the crater. Meanwhile, disaster had befallen Sgt Newton’s party. Before reaching the crater, the party had been caught by masses of falling earth and were buried in mud and slime – only Sgt Newton being visible. Captain Sergeant was standing buried up to his neck in debris but providentially was supported by a wooden beam wedged across the trench. Captain Maginn and Coy Sgt Major Tyers, who had searched for Sgt Newton’s party, after failing to find them in position in the crater, at once set about getting Sgt Newton free. The work continued in relays, took four hours by which time the Sergeant was blue with cold and hardly conscious. One other man was dug out but was dead. In all, fourteen men, including L/Cpl Holness, Riflemen Edwards, Butcher, Wright, Simmonds, Wood and Lakeman, all of whom had been with the Battalion in France since March 1915, were lost at this time and doubtless were suffocated in a couple of minutes.

Elsewhere, Sgt Perry had been killed by a bullet through the head and other men wounded but the Battalion took full toll of the Germans until they learned not to expose themselves. Meanwhile the enemy had localised the extent of the menace and concentrated his artillery, trench mortar and small arms fire on the crater and vicinity. In spite of the violence of the fire, the crater parties held the position securely. The enemy tried the effect of gas bombs but failed to shift the dogged defenders of the crater. At night, men of the RE came up to assist in the work of consolidation and, at the same time, efforts were made to excavate the trench in which Sgt Newton’s party was buried.

Christmas Day 1915 in the Front Line.

Captain McGinn, a 19th Battalion Company Commander and Coy Sgt Major Tyers were mistaken for the enemy by the RE when, in the darkness, they were returning from a reconnaissance of the crater. The RE opened fire but fortunately no one was hit.

Throughout Christmas Day, the crater parties and the front line Companies held their position. With little food, half frozen with cold and thick with mud and deep water everywhere, men sat on the fire step of the trenches, where possible, and huddled together for warmth, while the British and German artillery furiously lashed the trenches with high explosive and shrapnel.

The Company postmen introduced a touch of comedy when, after infinite labour, they succeeded in delivering cards inscribed: “A Merry Xmas”. It is feared that the recipients expressed themselves on the subject with more virulence than charm.

Relief and a Nightmare Journey Back.

The Battalion was due for relief by the 19th Battalion on the evening of Christmas Day. The first men of the relieving Battalion arrived at 6pm and, therefore all night long, exhausted men of the 19th Battalion continued to arrive in twos and threes and it was not until 1am the next morning that relief could be reported complete. The London Irish had a nightmare journey from the front line. Exhausted and chilled they splashed and struggled wearily through Bart’s Alley, the long communication trench which ran from the line to Vermelles.

Every step was a battle between tired humanity and forces of suction. As one foot squelched out of the coagulation of tenacious mud, the other foot sank deeply into the quagmire. Weighed down by their equipment and the mass of thick mud, which adhered to their clothes and rifles, men frequently stuck fast, completely unable to free themselves. It would be necessary for comrades to dig away the viscous ooze before such men could be released. Dozens of pairs of gum boots were left in the mud where the men, unable to extricate themselves, withdrew their feet and legs from thigh boots.

Lt Clement, an officer whose courage was considerably greater than his physique, was so securely fixed in the mud that he had to be lifted bodily out of his thigh boots. The gallant lieutenant, with a sense of fun and bright spirits not in the least affected, rewarded his rescuers with a tot of rum or a piece of chocolate according to taste and, like other many others, continued his journey in his stocking-ed feet. Eventually, the Battalion arrived at Sailly/Labourse and billeted there.

During the spell in the line, the Battalion had sixteen men killed and thirteen wounded – but it was necessary to send to hospital a considerable number of men found to be suffering from frozen feet. In some cases, the trouble was so serious that amputation was necessary.

The Final Days of 1915.

After a couple of days, spent largely in cleaning up and making food deficiencies, the Battalion relieved the 19th Battalion in the Hohenzollern sector on 28th December. The line was held for two days, during which time, the Bombers smartly repelled an enemy bombing attack on a sap head and the Battalion put in a good deal of work on the crater defences. Casualties to the extent of seven men wounded were suffered.

On 30th December, the 19th Battalion again took over the line and the Battalion withdrew to support between the front line and Vermelles, returning to good billets in Sailly/Labourse on the following day, 31st December.