Chapter 1 – Mobilisation, Training and First Actions.

Preparation for War.

On Saturday 1st August 1914, the London Irish Rifles paraded at Chelsea for the purpose of proceeding to Perham Down for annual training. At this time, the political situation abroad was rapidly going from bad to worse. Austria-Hungary had declared war on Serbia; Russia had ordered complete mobilisation, a state of war had been declared in German and in Great Britain, naval reserves had been called up.

Europe was preparing for, and expecting, war.

The Officers and men of the London Irish were excited at the prospect of this country being involved and it was rumoured that the Battalion orders for camp would be countermanded. The Battalion, however, en-trained at Paddington en route for camp, but other units of the Division were later ordered to remain in London.

The Battalion arrived in Camp in the afternoon but, as instructions to return to London were expected, nobody went to bed. During the night, the anticipated orders arrived and, early on Sunday morning, the Battalion returned to the Duke of York’s Headquarters at Chelsea. On arrival at Chelsea, the CO was without instructions and there was nobody in authority to issue orders. Shortly afterwards, however, Lord Esher arrived from the Territorial Association and advised the Commanding Officer to dismiss them to their homes with a warning to stand by for further instructions. Orders to this effect were issued and subsequently mobilisation cards were dispatched. Every man in the Battalion, except two, paraded. The absentees were one officer, who was in Canada, and one man, who was in India. The mobilisation of the Battalion was, therefore, very satisfactory and reflected great credit on the Commanding Officer, Lt-Colonel EG Concanon DSO TD and his officers.

Billeting Arrangements.

It was not generally known that, for every unit of the Territorial Force, orders had been prepared beforehand down to the smallest detail. The accommodation at Headquarters had been told off to certain Companies and the Schools nearby allotted to other Companies. Shopkeepers had been interviewed in connection with the supply of bread, meat and other necessary supplies and officers and companies detailed for various duties. In the early autumn of 1913, the Division had ordered, for senior officers and adjutants, a weekend staff tour to St Albans – the Battalion’s war station.

On this tour, officers were instructed to proceed to certain districts of the town to investigate billeting possibilities. There was no authority to enter houses and other premises and the accommodation had to be gauged by less obvious methods. Chimney pots furnished the clue and, by making an allocation of troops against pots, estimates were obtained. At this time, officers engaged on this task were not altogether pleased as it was thought to be rather a waste of time and less profitable than devoting the occasion to military training. However, in August 1914, when the troops had been settled in billets, it was found that the estimates obtained were extraordinarily accurate.

Recruitment and Equipment.

The days following the Battalion’s return to Chelsea from Camp were difficult for all ranks. Officers and NCOs worked night and day. Very little time could be devoted to the other ranks, who were confined to HQ most of the time. Recruits far in excess of the Battalion’s needs came in with a rush and had to be selected, medically examined and equipped. Owing to sudden demands from all Units, it was almost impossible to equip the men completely. Essential kit was difficult to obtain but the Territorial Association, whose Headquarters was also at the Duke of York’s and whose Secretary and staff had been good friends of the Battalion, did their utmost.

The spirit and conduct of the men was exemplary and, during those early days, there was no orderly rooms for crimes and drunks despite the fact that, by Act of Parliament, every man received five pounds in gold on mobilisation.

The Battalion moves to St Albans.

In August 1914, the Battalion set out on its march to St Albans, the route followed being: Edgware Road, Watling Street, Brockley Park, Elstree, along the Radlett and Park Street switch back to St Stephens – thence via side roads and avoiding Holy Hill to Clarence Park, St Albans. One night was spent in bivouacs at Edgware, the journey being completed on the next day. The march was a trying experience for the men. The weather was tropically hot and transport animals and vehicles, having been suddenly procured, were strange to the Transport Section. The heavy loads, which had to be carried, necessitated vehicles being manhandled up the steep hills leading to and out of Elstree. Nobody was sorry when the Division arrived at its destination and had been finally settled in billets. The district allotted to the Battalion comprised the Fleetville suburb and roads near Clarence Park – with Battalion Headquarters in the Adult School, Fleetville.

On the whole, billets were surprisingly good and the inhabitants showed a cheerful acquiescence in the billeting arrangements. Halls and Institutions in the Battalion area were very scarce and difficulty was experienced in giving indoor training in wet weather. The deficiency of Halls and Institutions for relaxation in the evening, and when training and fatigues were not taking place, was also a decided drawback.

Training for War.

From the moment of arrival at St Albans, intensive training began and, under the skilful guidance of Colonel Concanon, the second in command: Major Healy, the Adjutant: Captain Hamilton and the officers and NCOs, the Battalion improved in fitness and military efficiency. The training was rigorous but the enthusiasm of the men counterbalanced the tendency for the work to become monotonous. While officers directed the tactical exercises to marked effect, Instructor Sergeant Sgt Major Foley (Irish Guards) and Regimental Sgt Major Higgins worked wonders on the “square” – although on more than one occasion, after giving the precise detail for “Battalion will form Square”, Sgt Major Foley was heard to murmur at the result of the individual orders which followed.

The sunny August and September soon merged into a dull and dreary autumn but, regardless of the weather conditions, training continued.

Rumours and Spies.

In these early days, St Albans was, like many other places, a sea of rumours – Germans were suspected everywhere and everyone whispered the story of vast hordes of Russians moving through England to the coast to join the allies. Confirmation came from all sides. The Russians had been recognised by their headgear, their high boots, their fur collars and it was even mentioned that some had been identified by the snow which still adhered to their whiskers. Everybody knew that, to avoid being see passing through London, the Russians crossed the metropolis in their stockinged feet via the underground railway tunnels.

Efforts were made to check the activity of spies by throwing a cordon round St Albans, so many chill night were spent on Sopewell Mill. Two London Irishmen were reported to the authorities during the spy mania. It subsequently transpired that, by conversing in French, they had aroused the suspicions of the worthy folk with whom they were billeted. However there was one more serious incident affecting a member of the Battalion. The individual was suspected and, during a musketry parade, as he was stepping forward with his detail, his real name was suddenly called. His momentary reaction gave him away and he was promptly removed.

Winter, Duties, Training, Messing and Local Diversions.

Following the raids by units of the German Navy on the East Coast, the Battalion was dispatched to Braintree, Essex. Their duties here comprised trench digging and the construction of gun emplacements in connection with the outer defences of London. The work was a change from the severity of the previous training but the weather was appalling: rain soaking the troops night and day. During this period, guards were provided occasionally for Brigade HQ at Dunmow Castle. The sentries were kept awake by the hourly call of the civilian watchman, whose call was something like, “One o’clock m’lady, fine night”, or “four o’clock m’lady raining.”

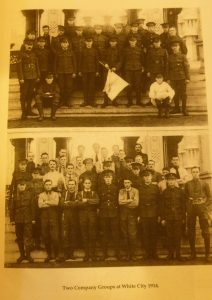

The Battalion returned from Braintree on 30th November 1914 and found that a large draft of men from the newly formed 2nd Battalion had arrived (on 14th November) from the White City. The draft consisted of men of a particularly good type and they were quickly absorbed into the Battalion. The extra strength enabled the Commanding Officer to send the Second Battalion a number of elderly men and others not physically equal to the tasks ahead.

Messing for the troops was arranged in a large marquee in Clarence Park, the Battalion parade ground. During the pleasant summer weather, this was fairly satisfactory and the troops were able to take their meals in the marquee or sitting on the grass or the park railings. In the autumn, however, the messing arrangements became definitely unpleasant. Troops paraded in the park in dark and chilly early hours for their breakfast and, on wet mornings, consumed their tea, bacon and bread in a state of considerable discomfort. The same miserable conditions were experienced in the evenings and, except for the boon of light, the midday meal was little better. Not all the troops could find shelter in the marquee or the park grandstand and the spectacle of the men having their meals in such conditions speedily brought about a change. Colonel Concanon was able to arrange for the men to mess in their billets.

The ladies of the various households in which the troops were accommodated, and who had done wonders to make their soldier guests comfortable, found that the new messing arrangements gave them additional scope. They delighted to augment the official rations from their own store cupboards and larders and, without disparaging the valiant efforts of the Battalion cooks, the men found that well cooked and well served food in the comfort of their billets was a vast improvement.

Christmas came and the inhabitants of St Albans made it a great occasion. The dances and concerts that were arranged gave great pleasures to the troops and the efforts of the townspeople were much appreciated by the men. However, the military authorities did not permit the festivities to last very long and chose Boxing Day for a test mobilisation of the Division.

New Year’s Day, too, was noteworthy. The Battalion paraded in Clarence Park at 430am and live ammunition was issued, the men were in tip toe of expectation, visualising a rapid departure for the front but, after waiting on the parade ground for a couple of hours, the excitement fizzled out and the live ammunition was collected and returned to store. On the following day, after inspection by the Commanding Officer, the Battalion was inspected by a Brigadier and went for a route march to Gorhambury. During the whole time, rain was teeming down and the Battalion returned to billets soaked to the skin.

Here and there, a laxity of discipline brought swift retribution as the two following instances will show. The first concerned a company on a route march under the charge of Lt G Dale. When the party came to a flooded section of road, the officer marched through the floods as though the water was non-existent. Not so the troops. The first few files followed the officer but the others broke ranks and climbed the slopes at the side of the road. Mr Dale halted the party and, after expressing himself vigorously, turned the party about and marched them back through the flood. Emerging beyond the water, Mr Dale turned his party and splashed them through the water once more, the march was resumed with the men soaked to the knees and a chastened and more disciplined force.

The other occasion concerned the whole Battalion. A rifleman of the Battalion failed to salute a General motoring past. The General noted that the offender was a rifleman of the London Irish and, in due course, the whole Battalion was called onto expatiate the crime of its unworthy member. Immediately after the next Church parade, the Battalion proceeded to the Nine Fields and a number of men were set out as convenient points as markers. Then, for a solid hour, the Battalion marched backwards and forwards saluting the markers.

As winter dragged on, the Battalion carried out a good deal of open order training and enlarged its experience by participation in field days and night operations arranged by Brigade and Division. From Clarence Park and to Nine Fields and thence to Lemsford Mills, Harpenden and Wheathamstead, the Battalion performed tactical exercises in mud, rain, snow and east winds in conditions of extreme discomfort. Nevertheless, the Battalion remained conspicuously cheerful.

The officers acquired an adroitness in manoeuvre and men a capacity for rapid movement and an intelligent appreciation of tactics. Guards and duties were plentiful and avoided where possible. There were, however, two varieties, which were much sought after by the men. With the Battalion possibly engaged in field exercises miles from billets, trundling a handcart laden with rations round the billeting area was a pleasure.

Similarly, those riflemen selected to form the young officers’ drill squad, found themselves fortunate indeed. The squad swiftly and happily executed wrong orders given by the trainee officers and were delighted by the chaos produced. The Sgt Major’s joy was less obvious and his pungent comments added to the fun.

Field firing at Dunstable came as a welcome interlude in the general scheme of training. On 14th January 1915, the Battalion caught the 750am train to Dunstable. On the range, the Battalion operated as in open warfare, using ball ammunition on square targets set in succeeding lines indicating enemy positions. The Battalion, advancing in waves by short rushes and giving covering fire alternately, brought the exercise to a grand conclusion by a burst of rapid fire followed by a bayonet charge of the whole battalion in line.

Apart from the military value of the work, the young soldiers were taught a valuable lesson by the old soldiers. The latter generously presented their ball ammunition to the young and ignorant who were delighted at the chance of blazing away a few extra rounds. Later, it dawned on them that the old soldiers had no trouble in preparing for the subsequent rifle inspection but their sweating barrels kept the young soldiers in a state of apprehension.

Through January and February, training continued without respite and the long succession of field days made the troops familiar with every inch of the St Albans district. Route marches were numerous and, occasionally, were extended unnecessarily owing, apparently, to inaccurate maps – or perhaps maps read wrongly. However, the men took it all in the day’s march as did the map reader when he heard the song, “and a little child shall lead them.” One such march took the battalion past Napsbury Asylum when it was pouring with rain and it was then that the phrase “Come inside” was supposed to have been coined.

There were occasions when field exercises were varied by visits to the range of Gorhambury and Mimms and one memorable day – 12th February – when the whole Division was reviewed in Gorhambury Park and crossed the lake in the park over a pontoon bridge constructed by the Divisional Engineers. The review was a magnificent display of men and material and, apart from the South African war date of the artillery, the sight was calculated to cause a thrill of pride to the most critical spectator.

Winter Sports.

During the winter, the sporting side was not overlooked and the Battalion was able to turn out a very respectable football team. On the second of January, the Battalion won the Brigade final by beating the 20th Battalion, London Regiment by three goals to two. This splendid result was followed by further successes when, on 9th January, the Battalion won their match against the 24th Battalion, London Regiment by five goals to nil and on 23rd February the ASC by seven goals to nil.

The Transport Section.

The Transport Section had much to do. Their training was conducted on lines as rigorous as those of the Companies. There was plenty of work and not a lot of fun. The first Transport Officer, McCreight, was unfortunately kicked in the mouth by one of his animals and so seriously injured that he had to spend several months in hospital. 2nd Lt B McM Mahon was appointed to succeed him. Several of the Transport Section were sent to Bishops Stortford for a course in shoeing and the remarks of the blacksmith tutor, when asked to turn out a fully qualified blacksmith in a period of eight weekends when it had taken him a lifetime, were unprintable.

In the winter of 1914, the horses suffered from a bad outbreak of strangles. This complaint, which is highly infectious, is characterised by an inflammation of the glands below the jaws. “Steaming” the horses’ heads comprised the treatment with sawdust, soaked with the steaming remedy, and put in the horses’ nosebag. For diet, the horses chiefly had brain mashes. One night, 2nd Lt McM Mahon was seeing the horses “done up” and put his hand in the mash to test the temperature before feeding. Surprised by its coarseness, the TO’s investigation revealed that the principal ingredient of the mash was sawdust. The Transport Officer said nothing outside the section but the individuals concerned were given something to remember.

The mascot of the Transport Section was a little fox terrier, who was a great favourite and who used to accompany the Section everywhere. After the terrier had been with the Section for a considerable time, when on a route march, he was recognised by his original owner, who promptly lodged a claim for the return of his dog. The claim was refused and much trouble ensued. The culmination of the dispute was a summons for 2nd Lt McM Mahon to appear at the local police court to answer a charge of dog stealing. What the upshot would have been, it is difficult to say but, at a critical moment, the Battalion was ordered to France and, just before departure, the terrier was returned to the bosom of his previous owner.

The arrival of several large round tubs of new GS harness was welcomed by the Transport Section but, putting together a multitude of loose and unfamiliar straps, called for all the energy and resources of the Transport Sergeant Hitchman. Having got the harness together, it was triumphantly fitted but the absence of the blinkers was something new to the horse as, from the corners of their eyes, they could see the big wheels of the limbered wagons rolling behind them and their consequent nervousness gave the Transport Section a rough time. One pair of the biggest horses took fright and bolted at full gallop with the GS wagon bouncing behind like a perambulator. Straight in to a bramble hedge they plunged, with Driver Easthill sticking nobly to his charge and piled up a kicking and struggling mess. Fortunately no serious damage was done to man, horses or vehicle.

Another duty of the Transport Section, apparently, was the erection of boxing rings and many a good man was trained and contests arranged by the capable ’second’ Sgt Hitchman.

The New Year brought joy to the Transport Section. The circus like cavalcade of tradesmen’s van and municipal water carts, which previously constituted the Battalion’s mobile equipment was replaced by limbers, field cookers, ammunition and hospital wagons. This was tangible evidence of progress.

Leaving St Albans for Embarkation.

By March 1915, it was patent to all that the Battalion was destined for overseas service but there was a persistent and disturbing rumour that the Battalion would go to India to relieve a regular Battalion. On more occasions than one, the troops were roused from their bed in the small hours of the morning and hurriedly paraded. After waiting hours in the cold and possibly getting as far as the station, the men were returned to their billets. In fact, the good people of St Albans became quite used to saying goodbye to their soldier guests.

Preparations for departure began in earnest on 4th March and, during the following few days, the men were subjected to inspection of person and kit every few hours and there was much marching to and from the Quartermaster’s stores. No one can think of the last few days at St Albans without remembering the work of the Quartermaster. The Battalion had cause to be grateful to QM Webb. He was the hub of the regimental universe, receiving the old outfit, issuing new rifles and kits, complying with a multitude of regulations and answering questions, both sensible and foolish, unceasingly. Quartermaster Webb was a model of good humoured efficiency. He worked at high pressure and had the satisfaction of seeing the Battalion equipped for active service in good time and complete to the smallest detail.

Confirmation that the Battalion had received its marching orders resulted in St Albans being crowded with visitors. Friends, relatives and sweethearts of the troops arrived in thousands and, on Sunday 7th March, the streets were swarming with people. There were few opportunities for family meetings as the troops were paraded hourly for ‘deficiencies’.

On 8th March, the roll was called at 8am, 11am and 245pm and a final kit inspection also took place. At a further parade at 5pm, the troops were ordered to be back at billets at 9pm. Again, the town was crowded with civilians, troops and transport. There was an atmosphere of pleasurable excitement. Marching troops sang lustily and yelled cheerful enquiries and comments to their comrades in other detachments.

The men slept the night in their kit and, on the morning of 9th March 1915, paraded at 5am, after saying a final farewell to their hosts in billets. The morning was bitterly cold and, in a flurry of snow, the Battalion moved off for St Albans station. The London Irish had been popular with the citizens of St Albans and there was a good crowd at the station to wish the men godspeed. The troops were in high spirits. The moment for departure had come! Soon, they hoped to be standing shoulder to shoulder with the survivors of that battered little force over the water.

The Battalion entrained at 850am in two parts. The first train carried “B” and “D” Companies and half the Transport. The second train accommodated “A” and “C” Companies and the remainder of the Transport.