Home » First World War

Category Archives: First World War

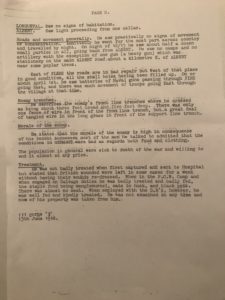

2/18th Battalion at Kherbet Adasseh

In the course of five weeks, the battalion had passed from the great heat and water scarcity of the desert to days and nights of continuous rain and it had now become bitterly cold. The area north of Jerusalem was a nightmare of rocky hills and no frontline was obvious. Some of the high points were held by the Turks, others not. One of the highest hills, midway between each Army’s position and thought to contain an enemy observation post, was one called Kherbet Adasseh.

On 18th December, a failed attempt had been made by the battalion to take Kherbet Adasseh before, on the night of 22nd/23rd December, the 2/18th Battalion was again ordered to take and hold the position

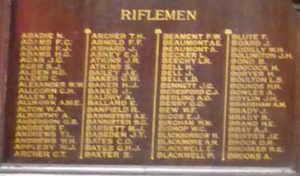

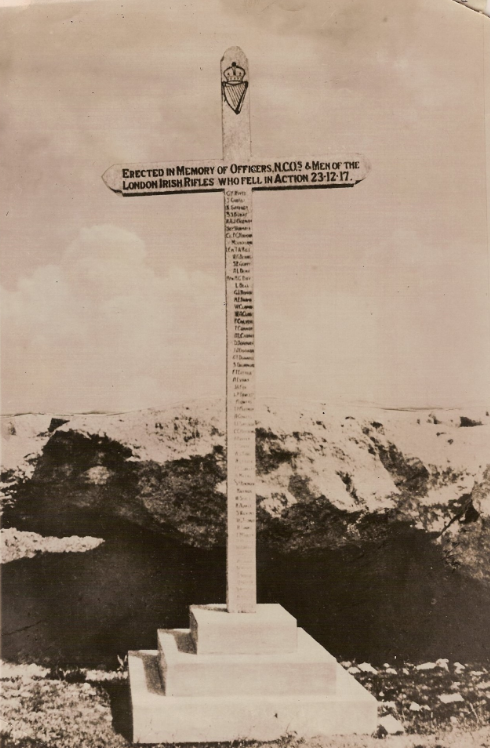

The following hours were a tale of almost complete disaster for the battalion. Only one out of 14 officers would return and the battalion strength of nearly 700 would be reduced to 130. According to the CWGC, 54 London Irishmen, killed on 23rd December 1917, are buried or named in Memorial at their cemetery in Jerusalem. It was a truly catastrophic day for the battalion and a wooden Memorial Cross would be erected by the Battalion Pioneer Sergeant on the exact spot of the disaster.

One of those killed at Kherbet Adasseh was Lt Whyte MC. In his last letter home to his wife Ethel in London on 18th December, he had written in a typically understated soldierly manner: “These last days have been pretty strenuous, and now that we are slack and more of less waiting for a few days, there is an inevitable reaction…”

It later emerged that two fresh Turkish divisions had recently arrived from Anatolia in preparation for an attempt to retake Jerusalem and it was these that the 2/18th Battalion had unexpectedly crashed into on the morning of 23rd December. A further unfortunate additional coda to the events at Kherbet Adasseh was that, when Battalion Chaplain Hickey helped to collect bodies a week later, he had noted that “practically every corpse had been stripped naked” and later it was found that some of Turkish dead were found “wearing uniforms and clothing taken from men of the London Irish.” A most regrettable outcome.

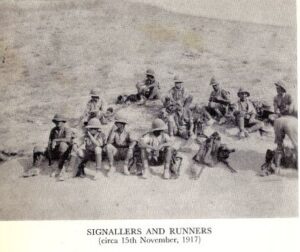

2/18th Battalion in Palestine, November 1917

About 2100 hrs on 6th November, I was ordered to take my “team” to Sheria Station. I was told that “the London Scottish had got a patrol at Sheria Station and that is to be the position for Battle HQ tomorrow. Take your team and set up shop at or near the Station.

The Brigadier will be along before dawn. If you can’t a find suitable spot at the Station, leave a guide there for the Brigadier.” I asked “How do I find Sheria Station?” The direction was pointed out to me (it was a black night; stars, but visibility not much more than ten yards) and was told the distance was 1½ miles over flat sand. I was warned not to bear off to the right or I might run into unfriendly natives. I knew there was a railway off to our left and that this ran to Sheria Station.

This order came at a bad moment. We had had a long tiring day on the 5th and, because I was new to the job, and it seemed it was nobody’s business to give me instructions or tell me anything, neither I nor my team had got as much rest as we could have had on the night of 5th/6th. Then on the 6th, we had been on the go from about 0400 up to the moment this instruction reached me. A total of forty pretty strenuous hours.

About half an hour later, (shutting my ears to a certain amount of quiet speculation as to the legitimacy of some of our betters) I got my team started off in single file, loaded down with sundry item of Signals “gear” – heliograph, a battery powered lap, which seemed to weigh a ton, flags etc. After about thirty minutes, there were quiet suggestions from the rear – “What about a halt?” To this I answered, “We’ll carry on for a bit”. This went on and on for quite a time. I was desperately afraid that if we once sat down, we would all be asleep in no time at all and convinced that the only hope of being at Sheria Station by dawn was to make the Station our first stop.

After what seemed like a very long time, when I was sure we had covered much more than 1½ miles and therefore must be off course, I decided to turn 90 degrees left and keep going until I hit the railway – but first, to be on the safe side we would retrace our steps for ten to fifteen minutes before turning for the railway. This we did and eventually struck the embankment.

Al this time, calls for a rest continued but I kept going. Here, I might remark that it is so much easier to lead than it is to be led. The man at the back has nothing to do but think of his own exhaustion, of the effort to put one foot in front of the other and his conviction that the stupid clot in front had been lost for the last hour. Whereas, the genius in front knows he is lost and is so worried that he will not have his party complete at the appointed spot at the appointed time, that he has no room in his mind to worry about anything else.

Having reached the embankment and turned along it, I was happy to know that we had only to keep going to arrive at Sheria Station but after doing not more than 100 yards, the man immediately behind me gripped my elbow and said quietly – “We’re on our own Corp!” He and I turned back and after 100 yards across came across my exhausted team. Lying about against the embankment, dead to the world.

I said to the man who had stayed with me: “we’ll take twenty minutes or so; we must be nearly there. Keep talking to me and I’ll talk to you – or we’ll both be asleep too.” We sat down and started talking – and that’s the last I remember until, about an hour later, we were all suddenly very wide awake as an ammunition dump started to go up about 200 yards ahead of us. Only ten yards ahead of us, I had seen a culvert through the embankment when returning to find my missing team, so we made a dive for that and rested in perfect security. In addition to the dump near the railway, there were three wagons of ammunition actually exploding in Sheria Station – so when that stout headed redhead of the 2/19th Battalion said quietly, “we’re on our own, Corp,” I would think we were almost rubbing our noses on the buffers of the first wagon. We had not seen a soul, either friendly or unfriendly, since leaving the Battle Headquarters. Mutiny, thank God.”

In the half-light before full dawn, we had the frightening experience of narrowly missing being skewered by our own side. The front line Brigade, left of the railway, was 180 Brigade, while right of the railway was 181 Brigade for this second day of the Sheria Battle – 7th November.

First to appear was 181 Brigade, with their left on the railway – the 2/22nd Queens – and they were not of course expecting to find anyone friendly in front of them. We were feeling very friendly indeed but letting them know this quickly enough to avoid being clobbered was a near thing.

Making not a sound as they advanced over the sand in open order”, with rifle and bayonet at “low left point, I was certainly glad that the Queens (known unofficially as the Bermondsey Bloodworms) were on our side.

At this moment, there had been no sign of 180th Brigade on the other side of the embankment so, to avoid another tense moment when they did arrive, I brought my whole party to 181 Brigade ground – and it was no doubt this, which caused us to miss seeing the Brigadier pass. It was late in the morning before I found the Battle Headquarters at the highest point on the first ridge beyond the Wadi Sheria.

I was delayed in finding Battle Headquarters because it was not where I expected it to be. Knowing the Brigadier would be on the highest spot he could find – certainly, the spot with the best view forward, I searched the ridge to the left of the railway, but there was no sign of him. I found him eventually on the ridge to the right of the railway – which was 181 Brigade ground. I think it was recognised that to cross a Brigade boundary was almost as serious as an invasion of foreign territory – but the Brigadier had a higher position and a better view of his own front from there.

We had been at Battle Headquarters about an hour with Turk shells skidding down our backbones to drop in the wadi behind us, when the Brigadier hurried away to the Headquarters of the 2/20th Battalion. The Brigade had come to an anchor; the Australian horsemen massed on a narrow front had tried and failed to burst a way out. He wanted to take a closer look and make a new plan in consultation with the Commanding Officers of the 2/20th and 2/19th, the front line Battalions.

No sooner had he left than the Officer Commanding the 2/19th Battalion hurried up the hill to consult the Brigadier, and was in discussion with the Brigade Major when a shell arrived in the middle of the party. Of the thirteen at Battle Headquarters at that moment, there were three killed and three wounded. The killed were Major Gray, commanding the 2/19th that day, a Sergeant, who I think had arrived with him, and one Runner. The Brigade Major was seriously wounded and two Signalers less seriously.

I think we seven who were left would have been happy to withdraw to the wadi behind us, but the thought of the Brigadier returning to his Battle HQ to find it had made a separate peace was too dreadful to contemplate. Two, however, were sufficiently quick witted to manage it and to appear almost heroic at the same time. Two men picked up the Brigade Major and staggered down the hill with him, treating him rather like a sack of potatoes, which cannot have been too good for a man with shell fragments through his left arm and into his chest on that side.

I was very puzzled afterwards because I could identify everyone on the Battle HQ at the time – except the two who saw, in the body of the Brigade Major, a legitimate means of getting off that ghastly hilltop. It was years later that I got the answer to the puzzle in a quite incredible way.

On 11th November about ten years later, say 1927, I was in a coffee house off Regent Street with a dozen others when, just before eleven o’clock, maroons warned us of the two minutes’ silence. This was rightly observed in those days and was tremendously impressive. We, of course, stood for the two minutes and on resuming our seats started talking of the war – instead of exchanging ideas on our own industry, in different sections of which we were all engaged and which was the purpose of our regular “coffee mornings.”

One of those present on this 11th November told a story of “early November” during the war – of one shell landing in the middle of a closely packed group on a hilltop in Palestine. I had known this man, whose name was Thomas, for some years in business. When he had finished his story, I said “That was 7th November 1917 and the hill was at Sheria, just beyond the wadi” and asked “What were you doing there?” He was an FOO with 180 Brigade Artillery and, together with his signaler, grabbed the body of the Brigade Major and rushed him down the hill.

Only two men in the world could have surprised me by telling that story (assuming that both had survived the last eleven months of the war) and yet the story, when it came, was told by a man, whom I had already known for a few years.

When, after twenty minutes or so, word came from the Brigadier to withdraw to the wadi (which was almost equally unhealthy), I dropped straight into the arms of my own “family” – the London Irish Signal Section, although I could have wished for a little more time to recover the wholly fraudulent air of nonchalance which is thought proper.

My story seems to be at variance with the History of the 60th Division by Colonel Dalbiac and published in 1927. He writes of 2/17th and 2/20th moving forward to secure a bridgehead over the Wadi Sheria at 1800 hours on the 6th and of Captain Travers with 2 ½ companies “soon after 1900 hours on the 6th”. Certainly, he does not say they secured the bridgehead, but the reader is left with that impression.

I have no doubt that the report received by 180 Brigade in the early part of the night of the 6th that a London Scottish patrol had reached Sheria Station was correct – however, this patrol clearly did not stay at the Station, but withdrew. Even Sheria Station was about 200 yards short of the wadi.

The first men to reach the Sheria Station and pass beyond it were the 2/22nd Battalion at first light on the 7th – the three men nearest to the embankment were caught in machine gun fire and killed about 100 yards beyond the Station – say 50 yards short of the wadi. These were the men, who had come across my party a few minutes before and we were watching them closely, every step they took, as we tried to figure out the position. Although they passed us when there was only a hint of approaching dawn, by the time they reached the Station about 200 yards forward, it was full daylight.

So there is no question of a bridgehead having been established beyond the wadi on the 6th. Another point I recall is that Lieut-Col Borton, commanding the 2/22nd Battalion, was awarded the Victoria Cross for his personal “recce” of the Wadi Sheria, and the ground beyond, during the night of the 6th/7th. He went across mounted and rode for about an hour or more during the night, watching the enemy preparing the ridge of our reception at daybreak. Although mixing with them, he was never challenged.

During the three days from dawn on the 6th to the evening of the 8th, the temperature were exceptionally high for November – something over a hundred degrees in the shade and, on one day, a hundred and nine was recorded. And, of course, there was no shade.

I think this highest recording must have been on the second day – the 7th – but I may be influenced in this by the fact that the 7th was certainly the toughest day of the three and the day that water shortage was most acute.

Shortage of water was a greater trial at this point than at any other time, although relieved temporarily to some extent by the capture of 25,000 gallons sunk in the sand near Sheria Station. Needless to say, we did not get the free use of this invaluable store ourselves, but we got something.

I think that it was at this time that I promised myself that if I ever got home again, the first thing I would do would be to go all over the house turning on all the taps – just for the pleasure of hearing the water running.

One certainly understood, as never before, the many Bible references to water. Man can go many days without food but even twelve hours without water – particularly at a time of great heat – is another matter.

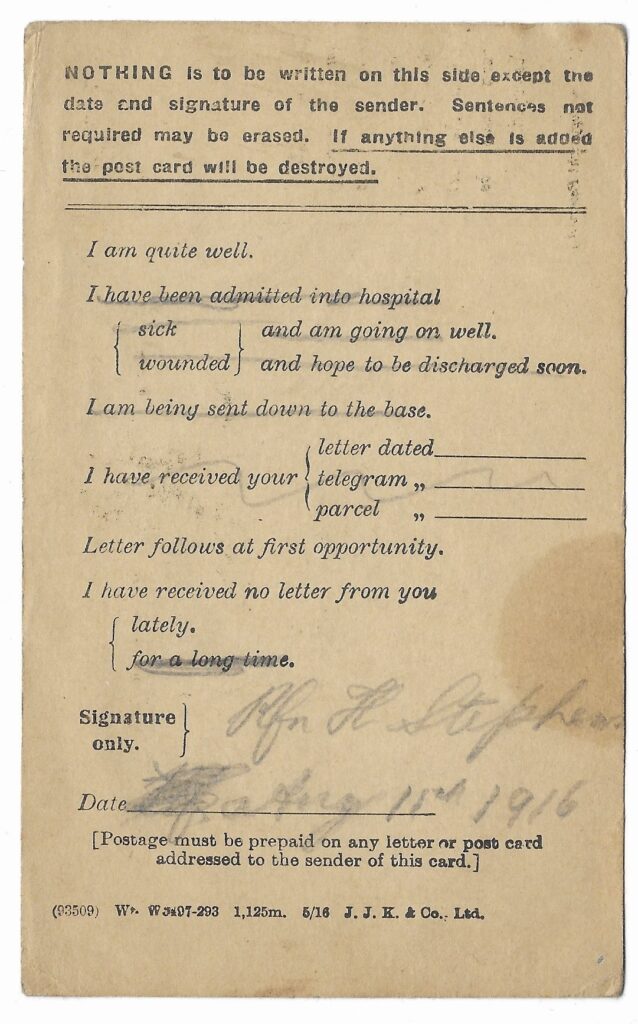

Rifleman Henry Norton Stephens

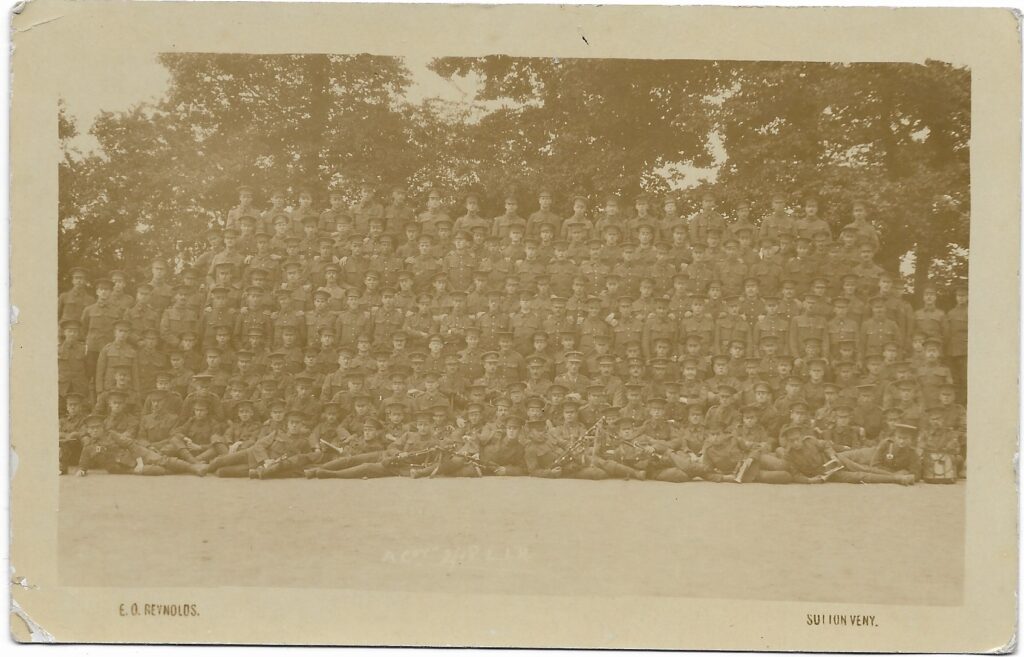

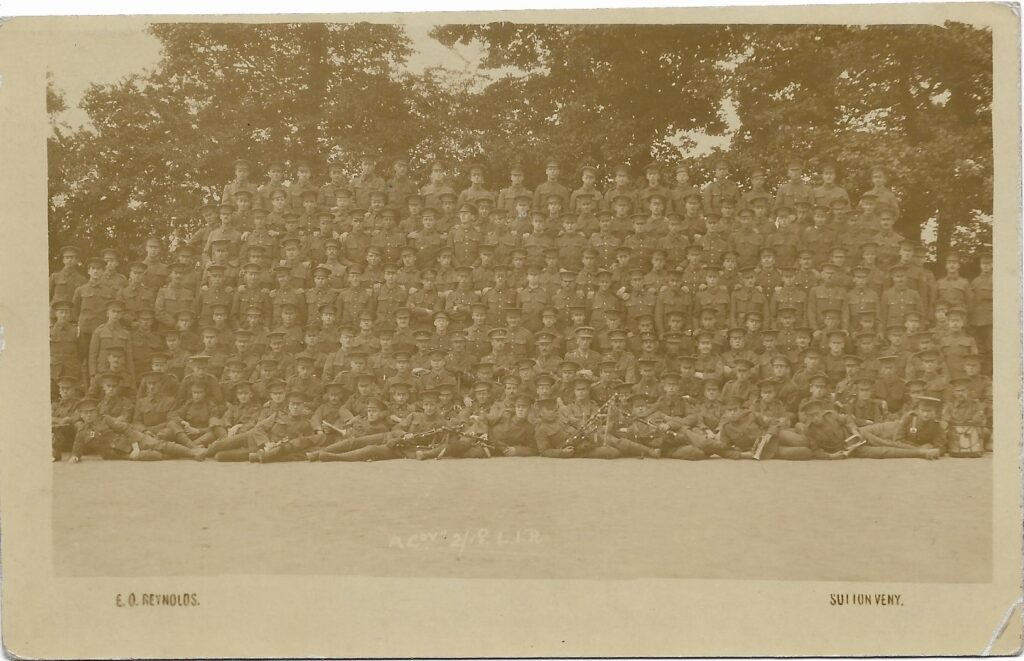

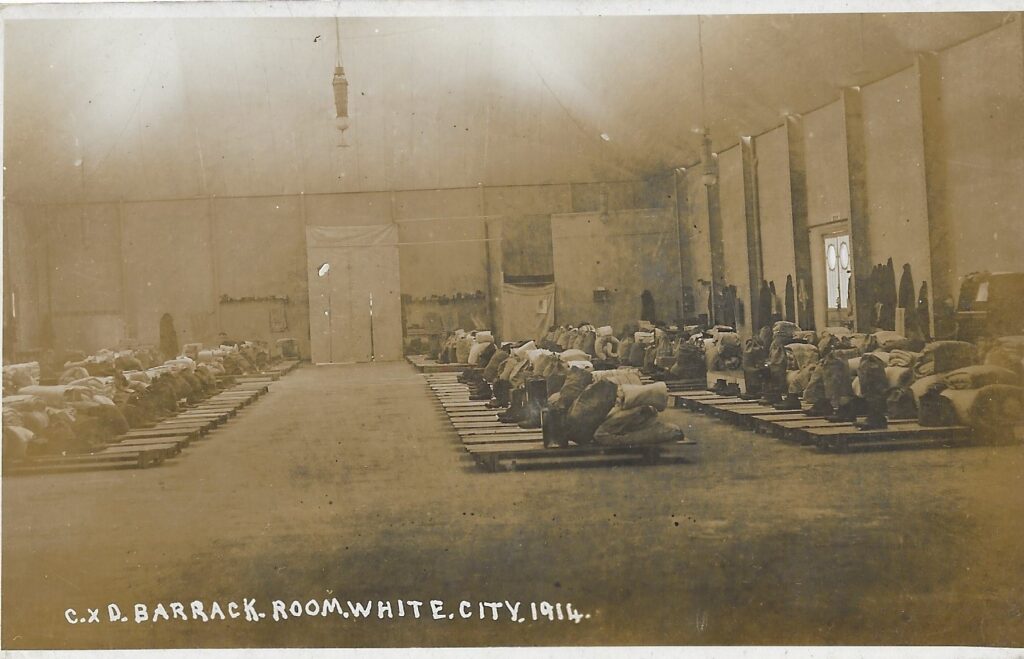

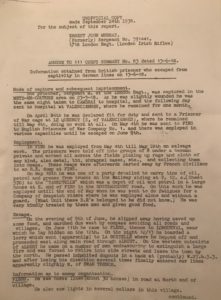

We are extremely delighted to have been sent a set of photographs and other interesting paper artefacts belonging to Rifleman Henry Stephens, who served with the London Irish Rifles during the First World War.

These fantastic documents have been donated to us by Henry’s granddaughter, Katy de Rooy, and she said in a note to us:

“I wonder if you would be interested in some memorabilia that I have come across whilst going through my late mother’s possessions. Her father, Henry Norton Stephens (my grandfather, born in 1897), was a Rifleman in 2/18th (Reserve) Battalion London Regiment and had obviously kept some artefacts from his time. These include several photos, a postcard, a pass-card, a discharge certificate, a newspaper article and what looks like notebooks from training camps (Scouting Notes?) and diary entries. He has also listed the camps/barracks where he was based between 1914 and 1916, although the print is sadly somewhat faded in much of these.

I would love for them to go to someone/somewhere that could archive them for future reference and wonder if your Association may like them?”

From an initial review of Rifleman Stephens’ papers, it is clear that he was living in Stamford Hill when he joined up in September 1914. Henry was immediately posted to the 2/18th Battalion (2nd Battalion London Irish Rifles) and trained with them for nearly two years in the UK before the battalion travelled to the Western Front at the end of June 1916, along with the rest of 60th (London) Division. At that time, the Division would be positioned in front line trenches near Vimy Ridge and, thankfully,. they missed the massive assaults at the Somme at the start of July.

From studying the LIR’s own records, it then appears that Henry was hospitalised at the end of September 1916 while in France, before being discharged from hospital in early 1917. Those dates make it clear that he did not travel with 2/18th Battalion to Greece in November 1916 but we are not able to trace other elements of Henry Stephens’ army service at this time.

We certainly know that Henry made it through the war to return to his family in north London, as Katy went onto tell us:

“After the war, he worked for a printmakers near Fleet Street and we have several leaflets documenting the workers (men only) annual coach trips to such hot spots as Clacton, Margate and Brighton.

Good to know he survived France to enjoy such pursuits ! I will let you know if I find anything else of interest in the family vaults.”

We have included a selection of Henry’s photos below and shall continue to study the other associated paperwork in the hope that we might be able to uncover further details about his time with the London Irish Rifles.

We would like to thank Katy de Rooy and her family for passing this fascinating set of photographs over to us.

Quis Separabit.

Frederick Curnow

We’ve recently received a note from Kieran Saunders about his great uncle, Rifleman Frederick Curnow, who was killed in France during May 1916:

“My Great Uncle Frederick James Curnow was with the London Irish Rifles in the First World War and was killed in action on 11th May 1916, aged 21. I have attached a photo of him in uniform and also a group photo including other unknown comrades, he is standing second from left. I believe his body was not found and he is commemorated on the Arras Memorial.

He was the eldest son of Frederick & Annie Curnow born 1895 in Chelsea, London and the family say his mother was so broken hearted that her son was killed that she died just 9 months later.”

Quis Separabit.

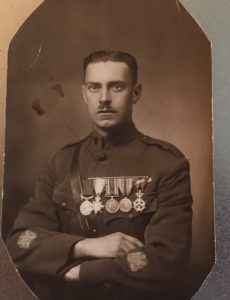

Sergeant EJ Murray

Rifleman George Grist

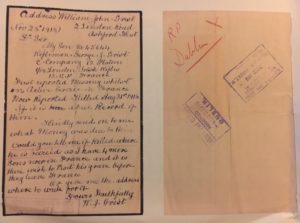

We were recently visited by Paul Grist, the nephew of Rifleman George Grist, who was killed on 31st August 1918 while serving with the 1/18th Battalion in France and is buried at Rancourt CWGC Cemetery.

Rifleman Grist, who was 19 years of age when he was killed, had joined the Royal Irish Rifles in 1917 and it seems he had been attached to the London Irish Rifles along with a number of others following the heavy casualties suffered by the battalion during March/April 1918.

During his visit, Paul Grist shared with us some very moving letters that had been received by his family in London following his uncle’s death, a remarkable testimony to a brave man.

Quis Separabit.

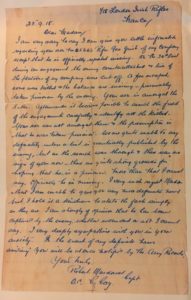

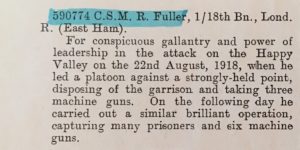

CSM Richard Fuller DCM

We were delighted to be visited recently at the museum by Stephen Foot, the grandson of CSM Richard Fuller who served with the 1/18th Battalion on the Western Front during the First World War.

Stephen kindly brought along his grandfather’s Distinguished Conduct Medal, which was awarded to him for his remarkable actions at “Happy Valley” in France on 22nd August 1918.

Rather unusually CSM Fuller was also awarded the Belgian Order of Leopold, which was only given to three men in total from the 47th London Division.

Following his distinguished service with the London Irish Rifles, Richard Fuller joined the Royal Irish Rifles and served for several years with that Regiment – he even joined up again with the Home Guard in 1939.

A remarkable man and we have now some most remarkable memories to treasure.

Quis Separabit.

Rifleman Arthur Oscar Berling

Service Number 593990

Died 02/09/1917

Aged 35

18th Bn. London Regiment (London Irish Rifles)

Son of Andrew Berling, of 15, Albert Square, Clapham, London; husband of Dora Annie Berling, of 9, Rue Fontaine, Paris.