Home » Articles posted by Richard O'Sullivan (Page 2)

Author Archives: Richard O'Sullivan

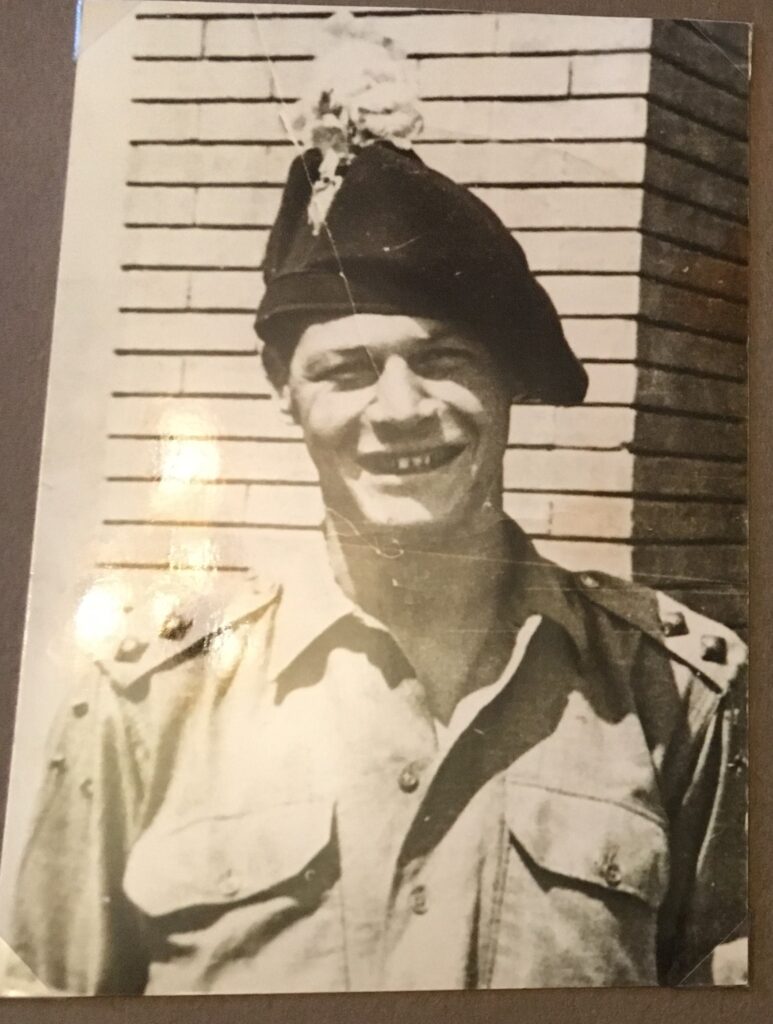

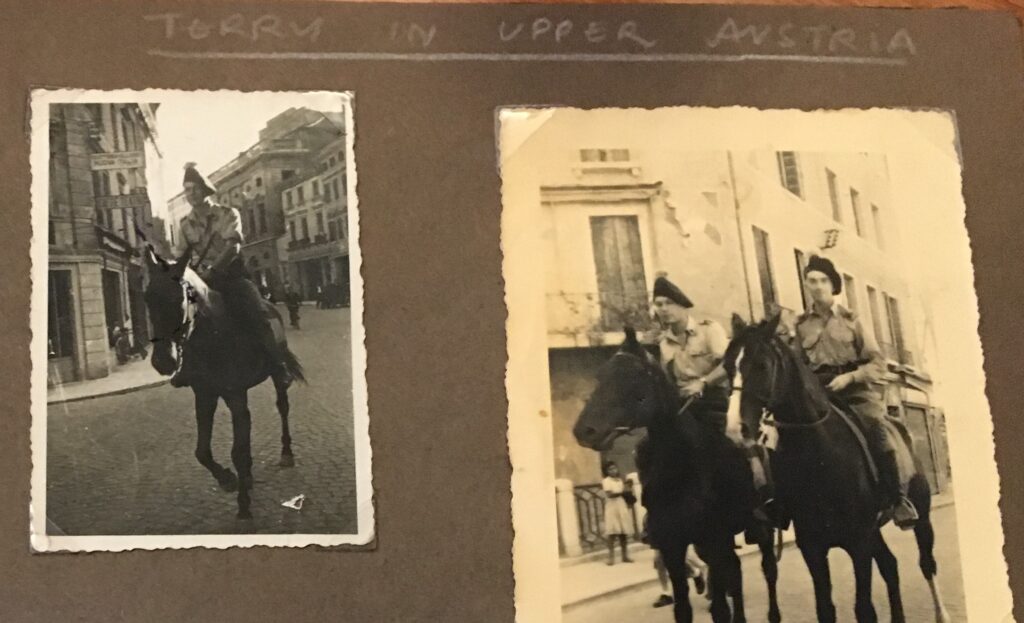

Lt Terry Flynn, 2 LIR in Italy

On Loos Sunday, we were delighted to meet with Sean Flynn, the son of Lieutenant Terry Flynn, who served with the 2nd Battalion London Irish Rifles during the Second World War. Although the details of Lt Flynn’s service period is not exactly clear, it is certain that he was serving with 2 LIR during its final advance through the Argenta Gap to the Po river in April 1945. He then went onto undertake peacekeeping duties with the battalion in Austria for the rest of 1945 and it seems that he may then have transferred to the 1st Battalion in 1946 when they were based in the Trieste area and completed his war time service with them in Italy.

During his visit to Connaught House, Sean Flynn shared some photos of his father as well as providing additional details about his background with previous strong family connections with the armed forces. We were also delighted that the Flynn family wishes to donate a number of interesting artefacts and some boxing trophies that Terry had won during the period of military training in the UK.

Sean went onto tell us that his father was born in 1923 and, after the outbreak of war, initially served with the Royal Armoured Corps as a “tankie” in North Africa and Italy before transferring to the LIR. It is probable that he was commissioned into the Royal Ulster Rifles after serving with distinction with a tank regiment.

As often was the case, Terry Flynn didn’t share too much detail with his family after the war but he certainly was deeply affected by some of the events that he witnessed during the final advances in Italy. He died on 17th March 2002 – perhaps fittingly for an Irish soldier – and left a legacy of heroic memory. We hope to perhaps learn more about his army career over the coming months.

Many thanks to Sean Flynn for visiting us and sharing his father’s story.

Quis Separabit

Rifleman Henry Norton Stephens

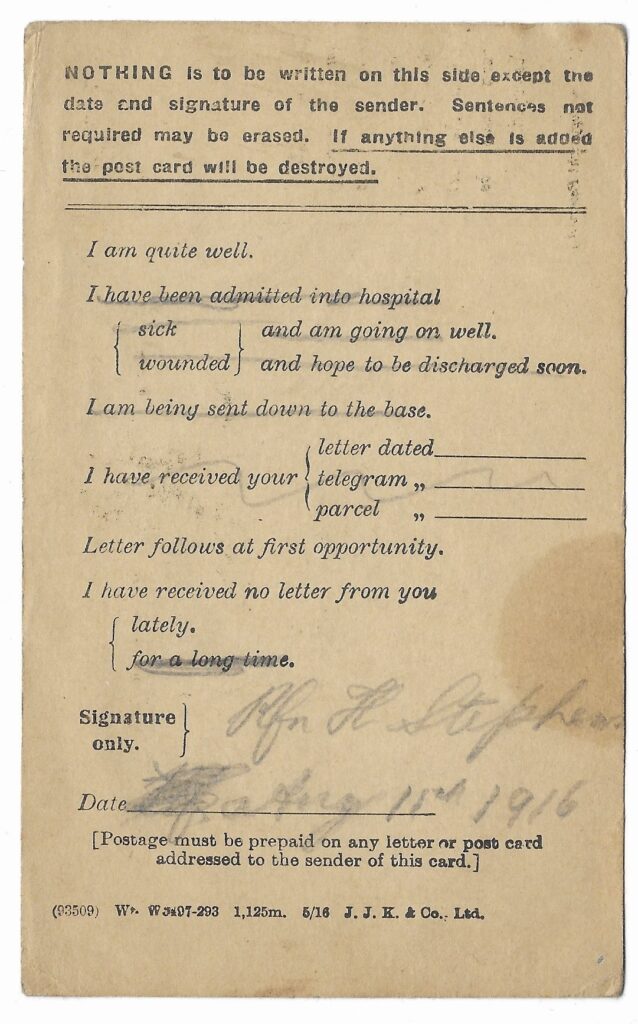

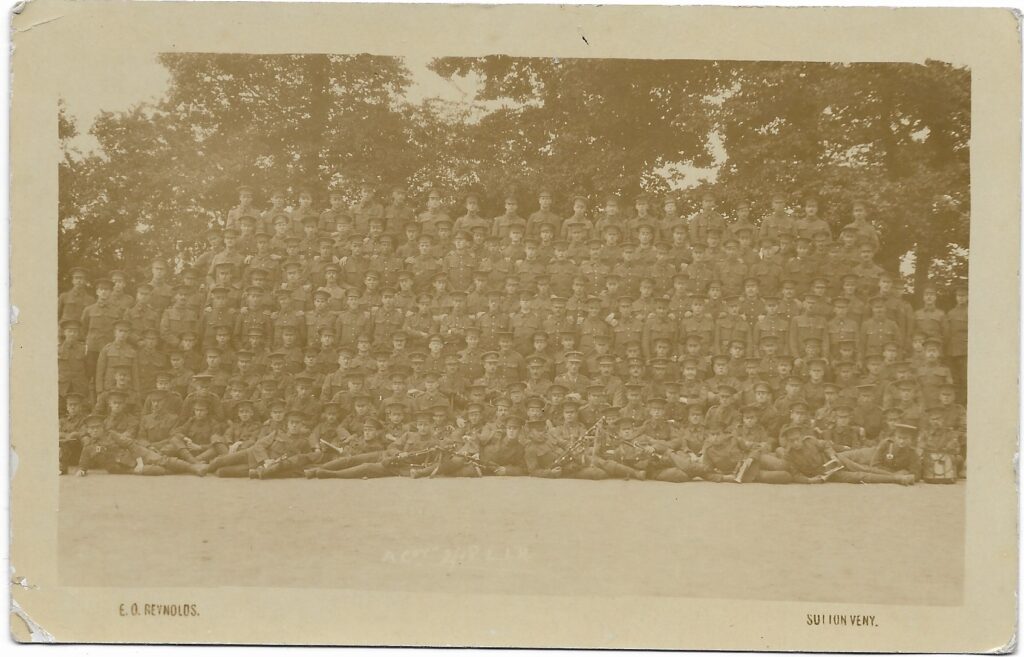

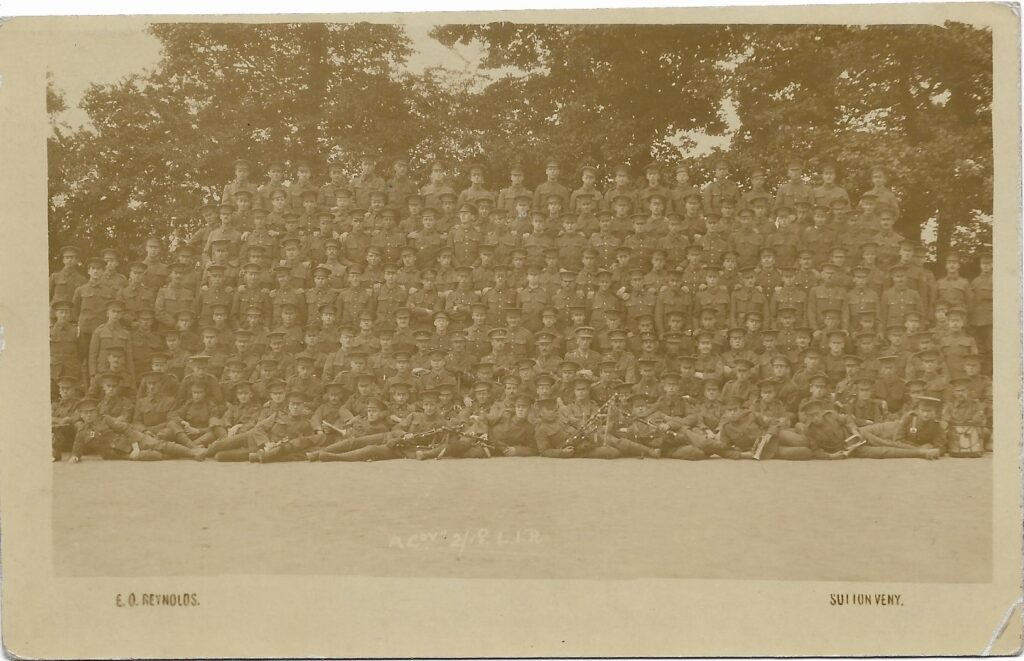

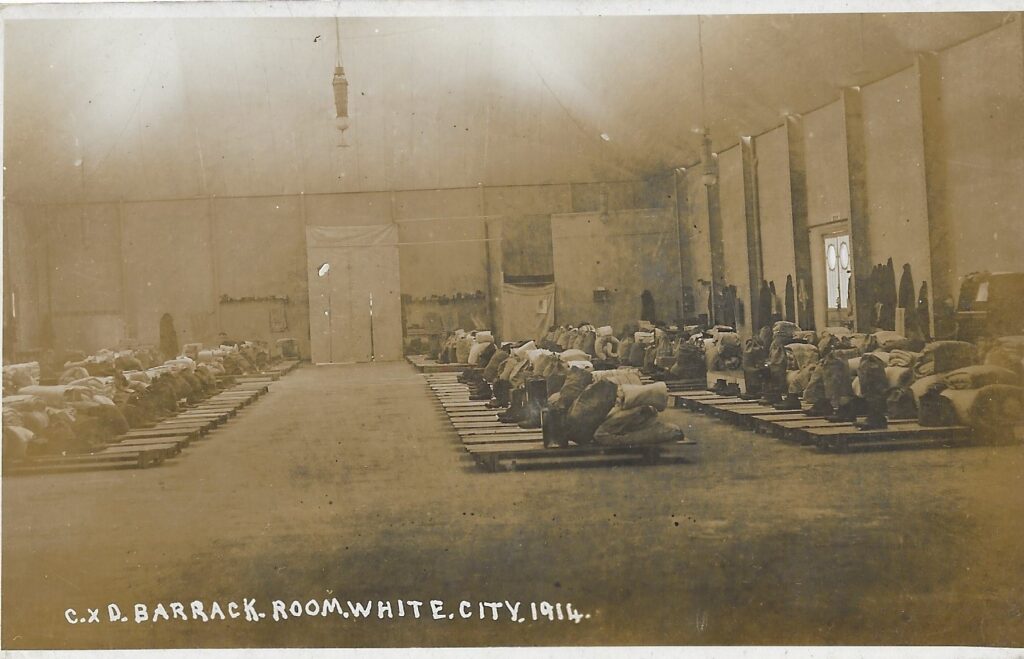

We are extremely delighted to have been sent a set of photographs and other interesting paper artefacts belonging to Rifleman Henry Stephens, who served with the London Irish Rifles during the First World War.

These fantastic documents have been donated to us by Henry’s granddaughter, Katy de Rooy, and she said in a note to us:

“I wonder if you would be interested in some memorabilia that I have come across whilst going through my late mother’s possessions. Her father, Henry Norton Stephens (my grandfather, born in 1897), was a Rifleman in 2/18th (Reserve) Battalion London Regiment and had obviously kept some artefacts from his time. These include several photos, a postcard, a pass-card, a discharge certificate, a newspaper article and what looks like notebooks from training camps (Scouting Notes?) and diary entries. He has also listed the camps/barracks where he was based between 1914 and 1916, although the print is sadly somewhat faded in much of these.

I would love for them to go to someone/somewhere that could archive them for future reference and wonder if your Association may like them?”

From an initial review of Rifleman Stephens’ papers, it is clear that he was living in Stamford Hill when he joined up in September 1914. Henry was immediately posted to the 2/18th Battalion (2nd Battalion London Irish Rifles) and trained with them for nearly two years in the UK before the battalion travelled to the Western Front at the end of June 1916, along with the rest of 60th (London) Division. At that time, the Division would be positioned in front line trenches near Vimy Ridge and, thankfully,. they missed the massive assaults at the Somme at the start of July.

From studying the LIR’s own records, it then appears that Henry was hospitalised at the end of September 1916 while in France, before being discharged from hospital in early 1917. Those dates make it clear that he did not travel with 2/18th Battalion to Greece in November 1916 but we are not able to trace other elements of Henry Stephens’ army service at this time.

We certainly know that Henry made it through the war to return to his family in north London, as Katy went onto tell us:

“After the war, he worked for a printmakers near Fleet Street and we have several leaflets documenting the workers (men only) annual coach trips to such hot spots as Clacton, Margate and Brighton.

Good to know he survived France to enjoy such pursuits ! I will let you know if I find anything else of interest in the family vaults.”

We have included a selection of Henry’s photos below and shall continue to study the other associated paperwork in the hope that we might be able to uncover further details about his time with the London Irish Rifles.

We would like to thank Katy de Rooy and her family for passing this fascinating set of photographs over to us.

Quis Separabit.

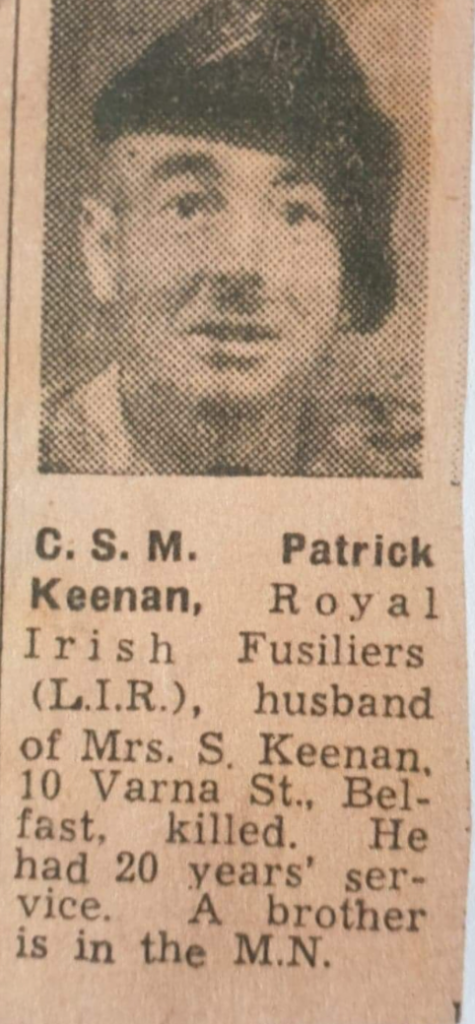

CSM Patrick Keenan

We recently received a note from Gerard Bryson, the nephew of CSM Patrick Keenan, who was killed on 9th September 1944 while serving with 1 LIR during the Gothic Line battles.

Patrick Keenan’s service record is not entirely clear but it seems that he started his army career with the Skins/Faughs during the early 1920s and served for 15 years before the war. He joined up with 1 LIR in Egypt or Italy in 1944 – perhaps he was shipped out from the UK during the year, the battalion needing reinforcements after Anzio etc.

This clip from ‘The London Irish at War’ confirms the circumstances of CSM Keenan’s death:

‘It was realised that the San Sevino Ridge was the key to Croce, and that Croce was the key to the whole Corps line….

The battalion stayed on for three days, enduring heavy bombardments and throwing back strong German patrols probing at danger-spots. Casualties were heavy. Lieutenant Johns in the Support Company was wounded by our own twenty-five pounders; D Company lost several killed and Lieutenant Michael Spiller and others wounded in a direct hit on a house.

B Company suffered the battalion’s greatest loss during that period, when CSM Keenan, a magnificent soldier and man, was killed in his slit trench by a mortar bomb bursting in the trees above.‘

In his note, Gerard went onto tell us more about the Keenan family:

“My uncle was the second born of a family of eight and his father James was in an artillery unit in the Boer war. His two brothers, James (who died before the war) and William (Skipper), were merchant seamen. His uncle William, also a seaman, appears on the Tower Hill memorial having died from exposure in a lifeboat after his ship the SS Brayhead was torpedoed in 1917. Clearly, our family has a long association with the military.

Patrick is survived today by his 83 year old daughter.”

Quis Separabit.

Patrick Pearse Kelly: 14th April 1936 – 28th July 2021

Pearse was born in Drogheda in the late springtime of 1936. He was extremely proud of his home town, always returning home at least once a year to visit close relatives and friends, to pay tribute to his local pubs and place a poppy wreath on the town’s War Memorial where his grandfather Patrick, a Royal Inniskilling Fusilier who died at Gallipoli in 1915, is commemorated. He was so proud to be a Drogheda man that there was a standing joke within the London Irish Rifles about his ancestors having been present at the Battle of the Boyne!

There is limited precise details known about Pearse’s army service, so what we have to hand is largely based on the recall of memories from Association Members. We do know that he joined the 1st Battalion London Irish Rifles in the late 1950s. Although Pearse was extremely keen to serve with the Royal Inniskilling Fusiliers, like his father and grandfather before him, he initially joined the Royal Irish Fusiliers before moving on to serve with the London Irish at the Duke of York’s. Pearse would also wear an Irish Reserve Army (FCA) Medal as he had attained seven years’ service with them before he moved to London. We’ve been informed that he served in the South Louth Infantry Battalion FCA and completed his Potential NCO’s course at the Curragh Training Centre before departing for England

His main duty within the London Irish was working as a cook in HQ Company for the Quartermaster’s Department, one of the most important jobs within a battalion, though he was regularly taken away from this role to play his part in battalion shooting teams and Courage Trophy teams (an infantry skills team competition, so he must have been fit!). Aside from the times that he wasn’t away soldering at weekends and camps, he ran the Officers’ Mess with great efficiency and continued through the changes in the late sixties when the battalion was reduced to a company of the North Irish Militia 4th Bn Royal Irish Rangers. Pearse would be awarded the Territorial Efficiency Medal, which he proudly wore alongside his National Service and FCA Medals.

Although Pearse’s service with the London Irish Rifles finished in the early eighties, he remained a staunch member of the Regimental Association, always on parade and marching at the various St Patrick’s Day, Loos Sunday and Remembrance Sunday Parades. He was also a member of the Combined Irish Regiments Association and attended their Annual Parades in Whitehall, turning out smartly dressed in his green regimental blazer, medals and caubeen.

Pearse ensured he attended pilgrimages run by the Association and was present at many battlefield tours over the years, visiting France, Belgium, Italy and Sicily and even joined a small group who visited the 69th Fighting Irish in New York.

Pearse’s untimely death is a cruel blow not only to his family, his children, and grandchildren but also will be felt across the whole Regimental family. He will be sorely missed at our meetings and parades and we shall miss meeting up together, whether it be at Connaught House, in the Victory Services Club, at the Civil Service Club or at the Royal British Legion in Paddington.

We shall miss Pearse…We shall definitely miss him.

Peter Lough.

Gerald Griffin playing at Pearse’s funeral in September 2021.

Rifleman Albert Leddy, 1924 – 2021

We have just received the sad news of the death of Rifleman Albert Leddy who served in Italy and Austria with G Coy, 2nd Battalion London Irish Rifles before becoming a piper with the 1st Battalion in Italy.

Albert had written a little bit about his life in Liverpool prior to being called up:

“When I left school at the age of 14, I started work as a chandler’s boy going out with a horse and covered wagon selling soaps and washing powder and other cleaning materials in and around Liverpool. Then I went to work in a stable for a haulage firm near to Liverpool docks, then later I was sent to another stable to take out a pony and trap used for carrying small loads or the odd bale of cotton. I later went back to the other stable to work with a one-horse wagon working around Liverpool docks and railways. I finished working for them and went to work for a shipping butcher in Old Hall Street and supplied many of the big ships that came into Liverpool docks with meat, veg and fish.

In October 1942, when I turned eighteen, I received my calling up papers for military service…”

When Albert was called up, he was initially posted to the Royal Artillery before transferring to the Faughs in 1943 and then sent out to Italy to join the Irish Brigade as part of a reinforcement draft. He transferred with 2 LIR in the front line in April 1944 just before the final Cassino battles. From the Liri Valley, he journeyed with the London Irish to Trasimeno, Rome and Egypt, returning to Italy in September 1944 for the Gothic Line winter battles, manning the Senio riverbanks and joining the final Kangaroo Army advance through the Argenta Gap up to the river Po in April 1945.

After seven months of rest in Austria, in early 1946, he transferred to 1 LIR, who were then based near Trieste and, there, he learnt to play the pipes. Piper Albert Leddy was de-mobbed from Italy in 1947.

His son, David Leddy, wrote to us to tell us more about his father:

“He was still playing the pipes as late as the last New Year (2020/21) to his fellow residents at his care home. He was really pleased with the pipers’ cap badge that the LIR sent to him and wore it with pride. My grandfather was a coal merchant in Liverpool just before the war and I understand that my father was his pony wagon driver, assisting him to deliver coal. After the war, my father moved to Warwick to live with his brother (Ted) and went to work in the motor industry. At first, he worked at the Ford Foundry in Leamington Spa for a short period, then moved to Coventry to join the Standard Motor Company producing cars. He moved back to Ford and later went again to work for the Standard Motor Company where he stayed for 21 years and, there, joined the works band, the Standard Triumph Pipe Band, with whom he played for many years.”

Albert was 97 years of age. A full, long life indeed !!

Quis Separabit

Faugh a Ballagh !

The London Irish Rifleman who walked to freedom

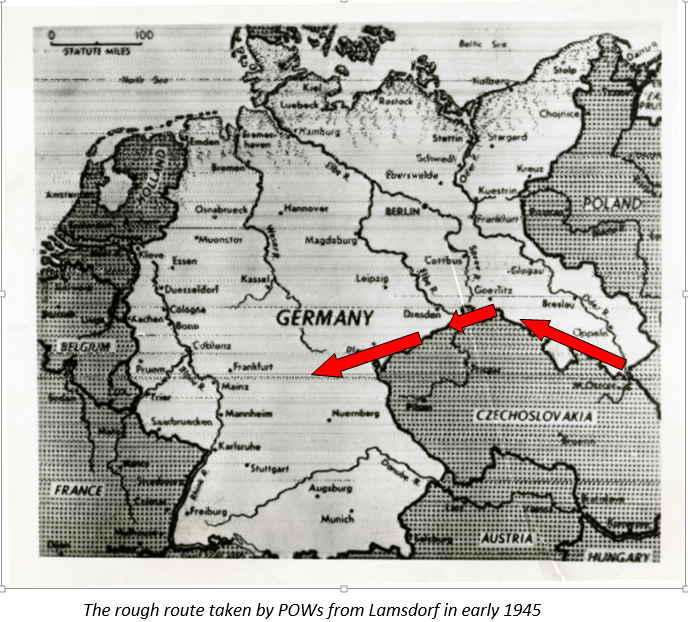

January and February of 1945 were among the coldest winter months recorded in Europe in the entire 20th century. In Silesia, then part of the Third Reich but now in Poland, temperatures fell to 25 degrees centigrade below freezing.

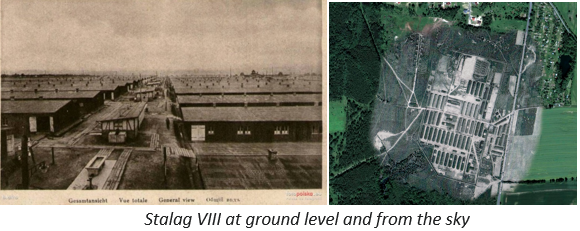

These were the conditions that faced Prisoners of War (POWs) at the Stalag VIII camp near Lamsdorf (now Gmina Lambinovice) when they were ordered to march west before the huge Soviet offensive that commenced in early 1945. Most of the POWs had been weakened by years of bad food. None had suitable clothes and they were now ordered to walk up to 25 miles a day. The evacuation was part of a massive movement from camps including the Auschwitz extermination camp in the path of the Red Army steamroller. It was a formula for suffering and death.

Around 80,000 men from Stalag VIII and other POW camps were driven west. They included David Moore, a native of Airdrie in Lanarkshire, who had been enlisted into The Cameronians in January 1940 before being transferred to the London Irish Rifles at the end of 1942, not long after he got married.

Moore had been dispatched to join the 2nd Battalion London Irish Rifles in North Africa at the end of November 1942 and was involved in the battalion’s battles in Tunisia, Sicily and along the Adriatic coast. In March 1943, he had been promoted to Lance-Corporal.

L/Cpl Moore was a section leader with No 7 Platoon, E Company when they were posted in January 1944 to a patrol outpost north-west of the village of Montenero in the upper reaches of the Sangro river valley. The battalion’s role was to watch for patrols from a German Mountain Regiment, which were harassing the Allied front line in the Abruzzi mountains 40 miles east of Cassino .

Lacking winter equipment and camouflage, E Company had been camping out for several days in deep snow drifts on Il Calvario, a high point more than 3,000-feet above sea-level. On the morning of 19 January after another freezing night, Moore was attending an ‘O’ Group with other section leaders in the tent of 7 Platoon commander, Lieutenant Nicholas Mosley, when German ski borne troops attacked. A mortar shell hit a tree about a foot from the door of the tent, injuring a couple men including Moore who suffered wound to his arms and head. Mosley ordered the riflemen into their trenches and to prepare to put up resistance, but they were quickly surrounded, Five London Irishmen had been killed in the short battle.

Most of 7 Platoon were taken prisoner including Lt Mosley himself, though he and three others managed to escape their captors as a result of a partially successful rescue by E Company’s reserve platoon and led by Company Commander, Major Mervyn Davies. David Moore and 19 of his comrades, some without boots, were marched under armed guard through deep snow into the mountains north of the Allied lines and he was then treated for his wounds at a hospital in Florence. At one point, when he awoke and saw the distinctive uniform of the nurses, Moore had thought that he had “died and gone to heaven”.

From Italy he was shipped by train to an enormous complex of POW camps in Silesia. His destination was Stalag VIII-B in Lamsdorf, which was also known as Stalag-344. The camp was originally built for no more than 15,000 but, by the end of 1944, it held an estimated 49,000 men, including more than 3,000 Allied prisoners. The military hospital and the infirmary of the camp were always overcrowded. Inspectors from the Red Cross criticised the poor conditions of the clothes of most prisoners and the lack of medication in the military hospital. In winter, the barracks were barely heated and, by 1944, there was a lack of water. Russian and Italian prisoners would be denied all medical assistance.

“(It was a) time he didn’t say very much about,” his son David Moore says. “On his release he said that his treatment had been reasonable though food was in short supply. Red Cross parcels helped to keep him alive.”

This was to change for the worse when the camp was evacuated in February 1945 when POWs were marched out in groups of around 200 into an arctic landscape. The Germans provided farm wagons for those unable to walk and teams of POWs often pulled the wagons through the snow because of the lack of horses. The reception was mixed in the German villages that they passed through on their journey west. There was occasional hostility and rocks were thrown by people angry about Allied bombing while on other occasions, penniless people shared whatever little food they had. At night, those with intact boots who risked taking their boots off to avoid trench foot found they couldn’t get their swollen feet back into them in the morning. Boots froze and were sometimes stolen. There was almost no food and the men had to scavenge, eating rats and cats to fend off starvation. Dysentery and frostbite were common and there were cases of typhus, which was spread by body lice. Some men died of exposure while they slept.

As the weather slowly improved in March, the widespread thaw turned roads into a quagmire of mud. Many POWs marched more than 300 miles before they reached Allied armies advancing into south-west Germany. Up to 3,500 British, Commonwealth and American POWs are estimated to have died in what is known as “The Death March.”

“It was a nightmare experience for my father,” his son says. “He spent the next ten weeks walking between 15 and 30 kilometres most days until he was finally released by Allied soldiers and repatriated to the UK. He suffered all the privations recounted by many who took part in and survived this horrendous experience including bitter cold and extreme hunger. I recall him speaking about it only when he recounted the kindness that he and a pal were shown by a German woman who cooked them a good meal when they arrived at her door with only a handful of rice and had asked her to boil it up for them. By the time he got home, he was suffering from flat feet, damaged ankles and metatarsalgia as a result of prolonged standing.”

After recovering his health, David Moore was transferred to the RASC where he remained until he was released to Army Reserve in May 1946. He then returned home to his wife Sadie in Scotland and they would have two children, three grandchildren and two great grandchildren who knew him, plus two others who were born after David’s death, at the age of 92, in January 2009.

A most remarkable story of human resilience.

A memorial was later erected on the site of Stalag VIII in memory of the thousands who died there and during “The Death March”.

The inscription on the sandstone plate next to the memorial reads: Stalag VIII: A place sanctified by the blood and martyrdom of the prisoners of war of the anti-Hitler coalition during the Second World War.

Major Desmond Woods, 2 LIR

We were delighted to have been contacted recently by Adrian Woods, the son of Major Desmond Woods, who served with the 2nd Battalion as Officer Commanding of H Company from October 1943 to June 1944 until he was wounded in the fighting near Lake Trasimene in central Italy.

As well as his note to us, Adrian also passed over some additional extensive written details of his father’s service with the London Irish Rifles that had been transcribed from an interview by military historian, Richard Doherty – it’s a most remarkable story indeed and these details will be filed in the Museum’s archives.

During his 8 months with the London Irish Rifles, Major Woods was present during some of the most momentous battle periods for the 2nd Battalion – at the Sangro river, near Monte Cassino and at Sanfatucchio to the west of Trasimene.

During the assault on Casa Sinagoga on 16th May 1944 , H Company formed the centre of the battalion’s advance which ultimately broke through the vaunted Gustav Line in the Liri Valley and it was here that Major Woods was awarded a bar to the Military Cross that he had received before the war – at the same time, he would unsuccessfully recommend Corporal Jimmy Barnes for a posthumous Victoria Cross for his part in that day of most bitter fighting for 2 LIR.

After being wounded and medically downgraded, Desmond Woods became a Training Major for the Italian Gruppi Cremona in northern Italy before undertaking a distinguished post war service overseas with the Royal Ulster Rifles and later with other units in Northern Ireland.

Quis Separabit.

CSM Ashton Frank Clarke

We have been been contacted by Jan Clarke, the daughter in law of CSM Ashton Clarke, who served in Italy with the 1st Battalion London Irish Rifles from 1943 to 1946 and where he was Mentioned in Despatches.

In her note to us, Jan explained that CSM Clarke had served overseas with the 56th (London) Division in Iraq, Egypt and Sicily, initially with the 10th Battalion Royal Berkshire Regiment, before transferring to 1 LIR after the bitter fighting for 168 Brigade near Catania and where the London Irish Rifles, London Scottish and the Royal Berkshires all suffered very heavy casualties.

Quite remarkably, before his death, Ashton had compiled a 300 page memoir tracing the whole of his war time service and we have been honoured that the Clarke family has sent a copy of it onto us and we plan to add excerpts of this very evocative story to the website in due course.

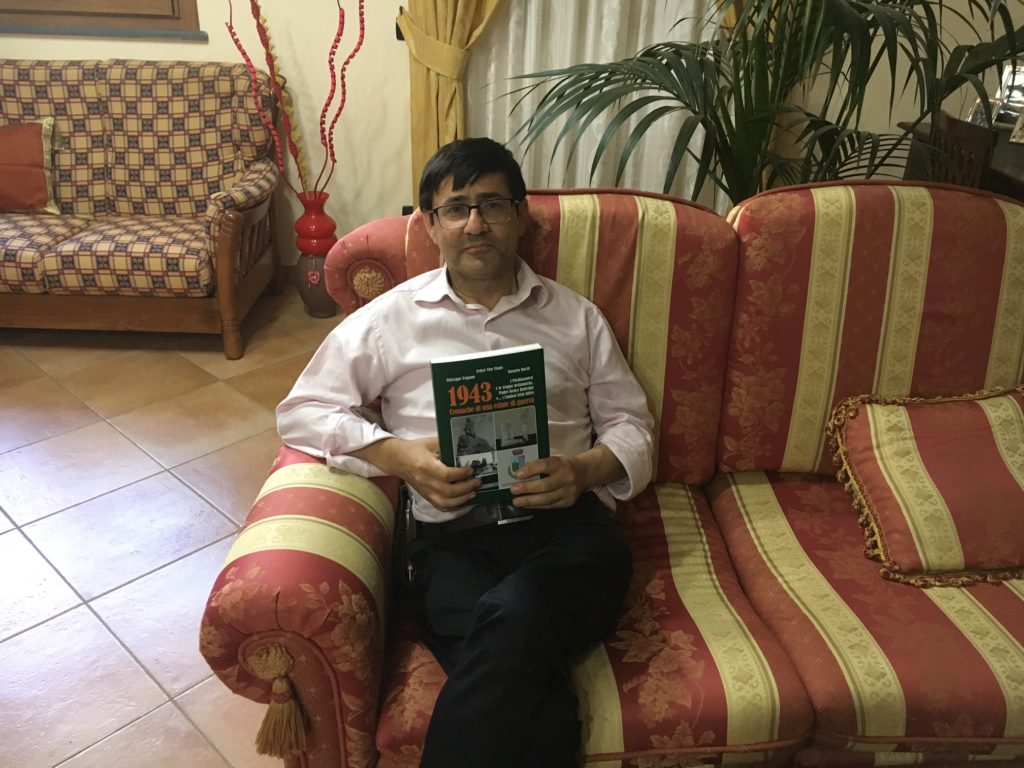

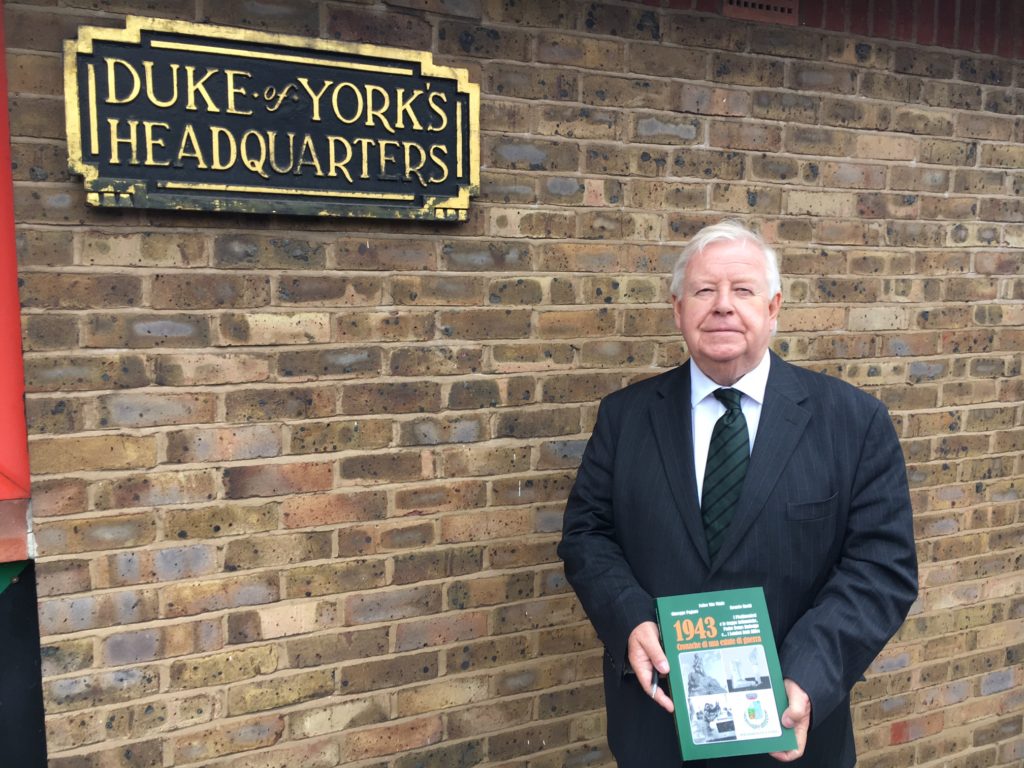

The London Irish Rifles in Piedimonte

During the recent Association visit to Sicily, we were delighted to receive a copy of a new book outlining the story of Piedimonte Etneo during the Second World War written by our friend Dr Felice Vitale. The book, which has been privately published, relates the background to the events of August and September 1943 when British troops stayed in the town after the final liberation of the island.

For the London Irish Rifles, in particular, it was a most memorable stay as the men, who had been engaged in very heavy fighting during July and August, were able to relax as well as commemorate the 28th anniversary of the Battle of Loos with a parade and service for the 1st Battalion who stayed in the town for five weeks. In fact, the war diaries state that “Piedimonte was the most confortable place the Battalion had stayed in since they left England”.

Felice’s own mother, Angelina, and his grand parents had witnessed the entry of the London Irish Rifles’ pipers into the town and this allowed him to gain a unique insight into the feelings of townspeople as they were being invaded by a large group of friendly Londoners with a very distinct Irish flavour.

The book is currently only available in Italian and can be viewed in the Regimental Museum and we hope to add a translated version to the website at some future time.

Great work indeed.

Grazie Mille.

Rifleman Louis Jeffrey

We are pleased to receive a note and some photographs from Chris Jeffrey with information about his father Louis, who served with the 1st Battalion in the UK, Middle East and Italy during the Second World War. Rifleman Jeffrey first joined up with the London Irish Rifles in May 1938 and was finally demobbed in June 1946.

In his note to us, Chris said:

“I know my father was based with Lord Gault’s HQ at the outbreak of war as an interpreter. Obviously they were forced to withdraw but I’m not sure if they got out via Dunkirk or Cherbourg.

This picture was taken in Mersham sometime in 1940/41 and shows the Pipes with Tara the Irish Wolfhound and Mascot. I believe my father was based in Hatch Park which was part of the Brabourne Estate before deploying to the Middle East. Part of his duties at that time was patrolling Romney Marsh on his motorcycle. He also met and married my mother, Mona, who was living at the time with her parents lived at Hatch Lodge – her father, my grandfather, had worked on the Brabourne estate.

This picture shows my father with the CMF in 1945 enjoying some skiing in Cortina which can be seen behind the group. My father is sitting on the ground far right at the front.

I know my Father was wounded at Anzio and sent back to Blighty to recover. He eventually arrived back at the Depot in Ballymena but I’m not sure how long he was there before returning to Italy to rejoin his Battalion.

He spoke fondly of his CO, Colonel McNamara, who was sadly killed by German mortars in 1944 while visiting the Bn as they were moving into the Senio Line. “