Pilgrimage to Castelforte, Anzio, Cassino, May 2024

Saturday 11 May 2024

2030-2300: Local commemorative events in Castelforte to mark the start of the Final Battle of Cassino at 11pm on 11 May 1944.

Overnight – Castelforte.

Sunday 12 May 2024

0830-0930: Remembrance Service at Minturno CWGC Cemetery.

1030-1200: Monte Damiano Battlefield Reviews, organised by the Gustav Line Museum.

1230-1400: Parade from Castelforte to Suio Alto.

1700: Parade to War Memorial in Castelforte.

1730-1900: Reception at Gustav Linea Association Museum in Castelforte.

Overnight – Castelforte.

Monday 13 May 2024

0900-1000: Amazon Bridge commemorations, along with the Royal Engineers/Monte Cassino Society.

1400-1700: Visit to the Abbey of Monte Cassino/Polish War Cemetery/Snakeshead Ridge.

Overnight – Cassino.

Tuesday 14 May 2024

1000-1100: Remembrance Service at Cassino CWGC Cemetery.

1400-1700: Liri Valley Battlefield review.

- Congo Bridge crossings on 14 May 1944.

- Piopetto crossing – 6 Innisks advance on 15 May 1944.

- ‘O’ Group for 2 LIR on 15 May 1944.

- Start Line for 2 LIR advance on 16 May 1944.

- Casa Sinagoga – Objective of 2 LIR attack on 16 May 1944.

- Colle Monache – Start of advance of 1 RIrF on morning of 17 May 1944.

- Piumarola – Fighting for 6 Innisks/2 LIR on 17 May 1944.

- Route 6 – Cutting of Via Casalina on 17 May 1944.

Overnight – Cassino.

Wednesday 15 May 2024

1000-1100: Commemorative Service at the German War Cemetery at Caira.

1200: Travel to Anzio.

1400-1500: CWGC at Anzio, Beachhead Cemeteries.

1600: “The Wadis”/Flyover/”The Factory”/E.F. Waters Memorial.

Overnight – Cassino.

Thursday 16 May 2024

0900-1100: Commemoration of the precise timing of 2 LIR’s attack on the Gustav Line at Casa Sinagoga south of Cassino.

Major-General Sir Sebastian John Lechmere Roberts KCVO OBE.

The funeral mass for Major General Sir Sebastian Roberts – the former colonel of the Irish Guards and Honorary Colonel of the London Irish Rifles who died aged 69 on 9 March — was held at the London Oratory on 13 April.

More than 1,000 mourners, including many retired Guardsmen, attended the event.

HM King Charles III was represented by General Sir Mark Carleton-Smith, former Chief of the General Staff. His Serene Highness Prince Josef-Emmanuel represented the Grand Duke of Luxembourg. HRH The Prince of Wales, the Irish Guards’ former Honorary Colonel, was represented by Major James Lowther-Pinkerton, Prince George’s godfather. The Princess of Wales is the regiment’s present Honorary Colonel. Major General Christopher Ghika, a retired Irish Guards’ officer, represented Her Royal Highness The Princess Royal.

The mass was celebrated by Father Ambrose Henley, Dean of Ampleforth Monastery, who also delivered the Homily.

Sir Sebastian were carried into The London Oratory by eight Irish Guardsmen led by a Guards officer. The opening hymn was “O Lord, my God, when I in awesome wonder”. The London Oratory choir sang the Kyrie from Missa Pro Defunctis by Giovanni Anerio. The first reading, from the Prophet Isaiah, was delivered by Julian Roberts, Sir Sebastian’s eldest son and a retired Irish Guards officer. The second reading, from St Paul’s letters to the Romans, was read by his second son Orlando, also a retired Irish Guards officer.

The readings were followed by the choir singing Pie Jesu from Gabriel Faure’s Requiem Mass. The gospel reading was from John Chapter 14: “I am the way, the truth and the life.” Salve Regina was sung during the offertory. Sanctus from Faure’s Requiem was also sung. During communion, the choir sang the Faure’s Agnus Dei followed by Ave Verum Corpus by Mozart.

After communion, the eulogy was delivered by Lucian Roberts, one of Sir Sebastian’s brothers who recalled his ebullient character and love of “dressing up” and painting. The final reading was delivered by Anthea Roberts, Sir Sebastian’s sister.

The last hymn was “Tell out my soul.” During the absolution at the end of the mass, the choir sang In Paradisium by Faure.

Sir Sebastian was piped out of the church with Saint Patrick’s Day, the Irish Guards’ regimental quick march.

The funeral mass was followed by a reception for mourners at St Winifred’s Hall next to the London Oratory.

Sebastian Roberts was born in Aldershot on 7 January 1954. He was the eldest of the 10 children of the late Brigadier John Roberts, former commanding officer of the 2nd battalion of the Welsh Guards and the Parachute Regiment, and his wife, the late Nicola (nee Macaskie) Roberts. Sir Sebastian went to school at Ampleforth College when Basil (later Cardinal) Hume was Abbot. Contemporaries remember him as “a theatrical figure, highly articulate and entertaining”, characteristics that Sir Sebastian was display throughout his life.

Sir Sebastian studied modern history at Balliol College Oxford and was commissioned into The Irish Guards in 1977.

In 2003, Sir Sebastian was appointed General Officer Commanding London District and Major General of the Household Division. On relinquishing the command in 2007, he was knighted and elevated to the Colonelcy of the Irish Guards in 2008. Sir Sebastian held the position until he handed it over in 2011 to the Duke of Cambridge, now The Prince of Wales, after leaving regular service the previous year.

He wrote the British Army’s doctrine of the Moral Component “Soldiering: The Military Covenant” and was also a broadcaster in demand during the HM the late Queen Elizabeth’s funeral in 2022.

Sir Sebastian married Elizabeth Muir, daughter of a former commanding officer of the Queen’s Dragoon Guards, who survives him along with their sons, Julian and Orlando, and daughters Cosima and Flavia.

Sir Sebastian was originally diagnosed with Marfan Syndrome when he was nine. The next time Marfan Syndrome was mentioned was in 1976, when he applied to join the Army. The retired Medical Corps Major General who headed the Medical Board at the British Military Hospital at Millbank was intrigued by his height, high palate, long fingers and bumpy chest. When Sir Sebastian asked if Marfan presented any problem, he said “only for your tailor, my boy,” and pronounced him fit to serve.

Sir Sebastian was first referred to London’s St George’s Hospital with his son and daughter in the early 1990s. “We learned a great deal that day: much more was known about the syndrome,” Sir Sebastian said in an interview published by St George’s Institute of Aortic Aneurysm & Aortic Valve Disease. “(W)e heard for the first time about the most serious eventualities: detached retinas and aortic aneurysms; but mercifully we were fortunate as a family: our symptoms were slight and gave no cause for concern.”

After Sir Sebastian was appointed to the UN force in Sierra Leone in 2001, a chest X-ray that was part of the UN medical, suggested something was wrong with his aorta. Further tests revealed a serious aneurysm.

“Within days I was given a new valve, and a few years later, a new aortic arch: in effect, a new lifespan, all owed to the professionalism, care and humanity of the people of St George’s, and the wider NHS,” Sir Sebastian said.

His family has asked for any donations in Sir Sebastian’s memory to be made to The Marfan Trust and The Irish Guards Charity.

Major-General Sir Sebastian John Lechmere Roberts KCVO OBE. Born 7 January 1954. Died 9 March 2023.

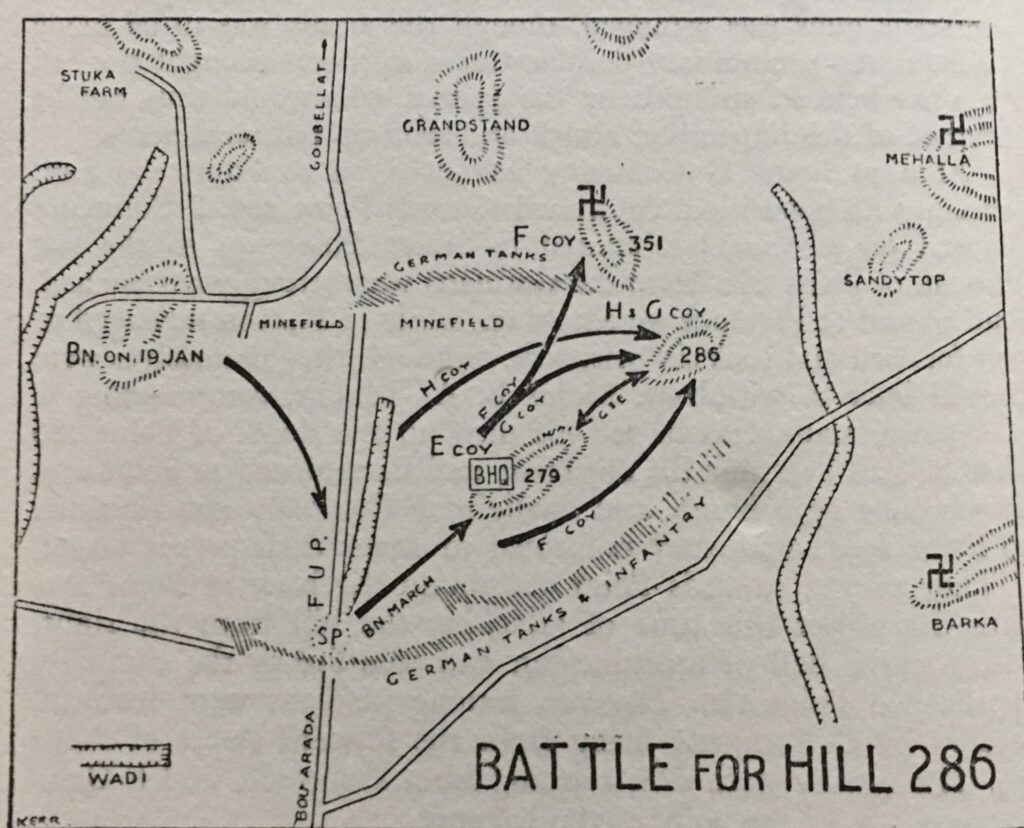

The Battle of Bou Arada – Hills 279/286

The Battle of Bou Arada was a bloody affair in which the 2nd Battalion, London Irish distinguished themselves, but with grievous losses. The night of 19 January 1943 had been spent just outside El Aroussa, and the next night the battalion moved into the plains to the west of Bou Arada. Another move was ordered, but no sooner had the battalion finished digging that they had to move once more. In fact the London Irish moved four times in four nights, and everyone became tired. On the morning of the 19th, they marched in extended line across the open plain via Bou Arada. Their job was to guard the brigade’s one line of communication, the lateral road from Bou Arada to Grandstand Ridge.

The enemy had been quick to see this weakness in the brigade’s disposition, and they occupied a hill, Point 286, only one thousand yards from the road. From there, they could observe, mortar and machine gun the brigade’s life line. It was an unpleasant situation and the London Irish were ordered to remedy it by driving the Germans off the hill and prevent its reoccupation. Instructions came at midnight and there was no time for a reconnaissance beforehand. The plan was for the battalion to form up on the lateral road at about 0330 hours on the 20th. ‘G’ Company were to lead and occupy Point 279, a lesser hill adjacent to Point 286, and ‘F’ Company were to follow and establish themselves on the reverse slopes of Point 279, while ‘H’ Company were to make a detour on the left and attack Point 286 from that flank. Support from the gunners, mortars, machine guns, and anti-tank guns was arranged, though the attack was to be made without any preliminary bombardment as it was though that the hill was not held in strength by the enemy, who would thus not be warned of the impending attack and send up reinforcements.

NIGHT ATTACK ON PT 286

At 0440 hours, ‘G’ Company advanced on to Point 279 and, meeting no opposition, continued towards Point 286. ‘F’ Company moved on as well, but started to attack Point 351 to the left instead of Point 286. Here the Germans were strongly entrenched, and 10 and 12 Platoons were held up, while 9 Platoon managed to get forward and took six prisoners, although they themselves were forced later to withdraw.

As he led his men up the slopes of Point 286, Major BA Tebbitt, commanding ‘G’ Company, realised that he had over-shot his objective, and he returned to Point 279. It was now 0730 hours, and daylight. ‘F’ Company also returned to Point 279, where they re-formed to attack their proper target. They moved towards Point 286 round the back of Point 279, with the object this time of attacking the hill from the right. There was a hail of machine-gun and rifle fire as the company approached Point 286. The two leading platoons went forward, covered by ‘G’ Company firing from the forward slopes of Point 279. The enemy were seen running from Point 286, and F Company went in at the point of the bayonet.

No sooner had they reached the summit of the hill and found that the enemy infantry had abandoned it, than German tanks and armoured cars were seen ascending the eastern slopes in a counter-attack. German mortars bombarded the hill, but the men of ‘F’ Company stood firm and the enemy cars and tanks were held off. Continued enemy fire took its toll and the gallant company suffered heavy losses, including Captain Ekin, their commander, and Lieutenant Vic Pottinger, both of whom were killed. Lieutenant A Cowdy was left in charge of the company, which was so reduced in strength that they were withdrawn. ‘E’ Company were warned to take over the positions on Point 286, and while the company “O” group were receiving orders, a mortar bomb dropped in one of the trenches, fatally wounding Captain JP Carrigan and two signallers.

The enemy by this time had occupied Point 286, and a further effort to drive them off had to be made. Led by Captain JV Lillie-Costello, ‘E’ Company bravely stormed the slopes. Some managed to reach the crest, but others were forced down to folds in the ground to gain cover from cunningly laid automatic and mortar fire. Lieutenant Josephs and his platoon held on, but the officer and most of his men were wounded. Several were killed. The Germans had given up some ground but they had not been driven off the hill. They bombarded the forward slopes of Point 279 where ‘G’ Company were in the open, valiantly trying to help their comrades with supporting fire. Their losses impelled ‘G’ Company back to cover in a wadi behind the hill, where they were joined by the staff of battalion headquarters, and the men of E Company who had survived the attack.

SECOND ATTACK

The Commanding Officer reported the situation to brigade, but the Brigadier emphasised the importance of securing Point 286, and a further attack by the London Irish was decided upon. The attack was made by ‘H’ Company, and no sooner had it got into its stride than the battalion area was dive-bombed by Stukas, and simultaneously ‘H’ Company were heavily mortared. Their Commander, Major JD Lofting, was wounded, and their Second-in-Command, Captain H Henderson, was killed. Men were falling fast, and the Commanding Officer ordered the company back. Some had managed once more to gain the summit, but it was impossible to hold it in the intense enemy fire.

Then word came that the Germans had been seen withdrawing yet again from Point 286. Major WD Swiney, Second-in-Command of the battalion, went forward with all that remained of ‘H’ Company. They went up as unobtrusively as possible, a section at a time, and despite continuous mortaring, they occupied the hill-top. They remained there for the rest of the day, gaining such cover as they could on the bald, rocky hill, where the ground was so hard that they could not dig in. Firing died down in the afternoon and desultory shelling and mortar fire was the only sign of enemy activity to break the uneasy silence of the battle-field.

The London Irish had gained their objective, but at a crippling cost. Nearly all the officers had been killed or wounded. ’F’ Company had no officers left, and losses in non-commissioned officers and men had been extremely high. That night the battalion medical officer, Captain LJ Samuels, who had done great work during the day, organised the cooking for the men. Food was prepared in a small culvert under the Goubellat-Bou Arada road, and sent up to the companies. Men of ‘E’ and ‘F’ Companies were on Point 279, ‘H’ were on Point 286, and the rest in the wadi below Point 279.

GERMAN COUNTERATTACK

Shortly after midnight, a runner came in from ‘E’ Company and reported that German tanks were climbing the slopes of Point 279, with infantry in the rear. The Germans overran the posts on Point 279 and fired for all they were worth into the wadi where battalion headquarters were quartered. In the darkness all communications within the battalion were disrupted. The companies were scattered and the fighting became very confused – the Germans seemed to fire wildly in all directions, and kept up a demonic yelling as if to bolster up their own courage. They withdrew as suddenly as they appeared, and the tanks moved smartly after them. At daylight the position was once more normal. The London Irish were on Point 286, and the enemy had gone.

Final casualties in the Battle of Hill 286 were: 6 officers and 20 other ranks killed; 8 officers and 78 other ranks wounded; 6 officers and 130 other ranks missing. Many of the latter were confirmed later as having been wounded and taken prisoner. The Divisional Commander and Brigadier Nelson Russell visited the battalion after the battle and thanked them for the part they had played in a vital operation.

BRIGADIER RUSSELL COMMENDS THE LONDON IRISH

Later the Brigadier (Russell) recorded officially as follows:

“The London Irish Rifles were a fine battalion, first-class officers and non-commissioned officers and good men all keen as mustard. They had been working together for three years. They possessed a good ‘feel’ and were proud of their battalion, as they had every right to be. They attacked with great spirit and after hard fighting drove the enemy off Point 286. But then came the trying time. It was practically impossible to dig in on the hard rocky slopes, and all through the day they were subjected to heavy artillery and extremely accurate mortar fire. This fine battalion refused to be shelled off the position. What they had, they held. But at heavy cost. I never hope to see a battalion fighting and enduring more gallantly. Nor do I want to witness again such cruel casualties.”

A VETERAN REMEMBERS

In 2011, Sgt Charles Ward, who was serving with ‘’G’ Company at Bou Arada at the time, recalled what had happened :

“We had to move over from one side of the road to the other side. As we moved across the road, we got shelled and we dropped into a wadi. I was leading my section along the wadi when suddenly a voice said ‘run’. I just said to the men ‘come on’. We ran down the wadi, got round a corner and I heard a shell explode behind. Going back, I found three men wounded, lying in the wadi, and I patched them up the best I could and waited until the stretchers came. Our platoon commander (2nd Lieutenant) Hardwick was one of the wounded. Then I continued to the forming up point ready for the attack.

This was all in broad daylight – it was crazy really. You knew you would be half way across and the enemy would throw everything at you. During that night, everyone assembled including our bren carriers, You could hear them forming up. The attack went in very early the next morning and we went to the first hill. And then to the second hill and nothing happened. It was then on the third hill (286) that all hell broke loose.

We holed up in a large depression in the ground, being shelled constantly. The Royal Artillery Forward Observation Officer ordered me to go up to the top of the hill to identify from where the shells were coming. I could see they were coming from a farmhouse about half way down on the plain behind the hill.

So I got back and discovered that a shell had fallen where I had been lying and left one or two injured. The artillery officer got the medical people to pick up the wounded and we then decided that there was no future in staying there and ordered a smoke screen. So we all withdrew and dropped into another wadi.”

Read more about Hill 286 here.

2/18th Battalion at Kherbet Adasseh

In the course of five weeks, the battalion had passed from the great heat and water scarcity of the desert to days and nights of continuous rain and it had now become bitterly cold. The area north of Jerusalem was a nightmare of rocky hills and no frontline was obvious. Some of the high points were held by the Turks, others not. One of the highest hills, midway between each Army’s position and thought to contain an enemy observation post, was one called Kherbet Adasseh.

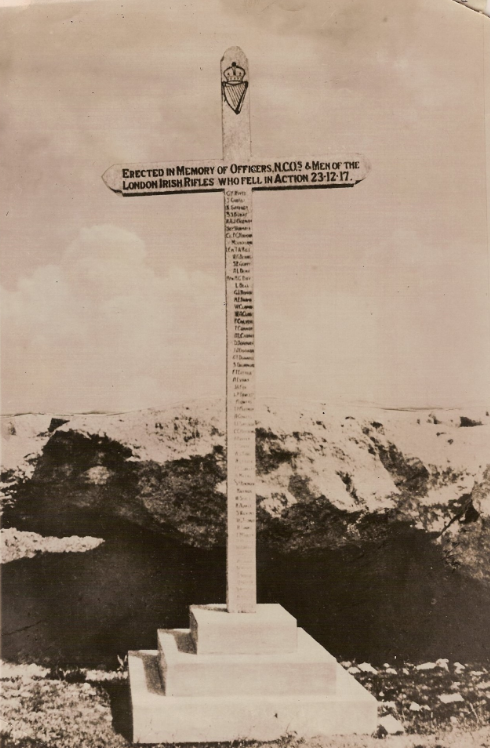

On 18th December, a failed attempt had been made by the battalion to take Kherbet Adasseh before, on the night of 22nd/23rd December, the 2/18th Battalion was again ordered to take and hold the position

The following hours were a tale of almost complete disaster for the battalion. Only one out of 14 officers would return and the battalion strength of nearly 700 would be reduced to 130. According to the CWGC, 54 London Irishmen, killed on 23rd December 1917, are buried or named in Memorial at their cemetery in Jerusalem. It was a truly catastrophic day for the battalion and a wooden Memorial Cross would be erected by the Battalion Pioneer Sergeant on the exact spot of the disaster.

One of those killed at Kherbet Adasseh was Lt Whyte MC. In his last letter home to his wife Ethel in London on 18th December, he had written in a typically understated soldierly manner: “These last days have been pretty strenuous, and now that we are slack and more of less waiting for a few days, there is an inevitable reaction…”

It later emerged that two fresh Turkish divisions had recently arrived from Anatolia in preparation for an attempt to retake Jerusalem and it was these that the 2/18th Battalion had unexpectedly crashed into on the morning of 23rd December. A further unfortunate additional coda to the events at Kherbet Adasseh was that, when Battalion Chaplain Hickey helped to collect bodies a week later, he had noted that “practically every corpse had been stripped naked” and later it was found that some of Turkish dead were found “wearing uniforms and clothing taken from men of the London Irish.” A most regrettable outcome.

Sergeant Charles Ward’s 103rd Birthday.

You can view an interview with Charles Ward here:

2/18th Battalion in Palestine, November 1917

About 2100 hrs on 6th November, I was ordered to take my “team” to Sheria Station. I was told that “the London Scottish had got a patrol at Sheria Station and that is to be the position for Battle HQ tomorrow. Take your team and set up shop at or near the Station.

The Brigadier will be along before dawn. If you can’t a find suitable spot at the Station, leave a guide there for the Brigadier.” I asked “How do I find Sheria Station?” The direction was pointed out to me (it was a black night; stars, but visibility not much more than ten yards) and was told the distance was 1½ miles over flat sand. I was warned not to bear off to the right or I might run into unfriendly natives. I knew there was a railway off to our left and that this ran to Sheria Station.

This order came at a bad moment. We had had a long tiring day on the 5th and, because I was new to the job, and it seemed it was nobody’s business to give me instructions or tell me anything, neither I nor my team had got as much rest as we could have had on the night of 5th/6th. Then on the 6th, we had been on the go from about 0400 up to the moment this instruction reached me. A total of forty pretty strenuous hours.

About half an hour later, (shutting my ears to a certain amount of quiet speculation as to the legitimacy of some of our betters) I got my team started off in single file, loaded down with sundry item of Signals “gear” – heliograph, a battery powered lap, which seemed to weigh a ton, flags etc. After about thirty minutes, there were quiet suggestions from the rear – “What about a halt?” To this I answered, “We’ll carry on for a bit”. This went on and on for quite a time. I was desperately afraid that if we once sat down, we would all be asleep in no time at all and convinced that the only hope of being at Sheria Station by dawn was to make the Station our first stop.

After what seemed like a very long time, when I was sure we had covered much more than 1½ miles and therefore must be off course, I decided to turn 90 degrees left and keep going until I hit the railway – but first, to be on the safe side we would retrace our steps for ten to fifteen minutes before turning for the railway. This we did and eventually struck the embankment.

Al this time, calls for a rest continued but I kept going. Here, I might remark that it is so much easier to lead than it is to be led. The man at the back has nothing to do but think of his own exhaustion, of the effort to put one foot in front of the other and his conviction that the stupid clot in front had been lost for the last hour. Whereas, the genius in front knows he is lost and is so worried that he will not have his party complete at the appointed spot at the appointed time, that he has no room in his mind to worry about anything else.

Having reached the embankment and turned along it, I was happy to know that we had only to keep going to arrive at Sheria Station but after doing not more than 100 yards, the man immediately behind me gripped my elbow and said quietly – “We’re on our own Corp!” He and I turned back and after 100 yards across came across my exhausted team. Lying about against the embankment, dead to the world.

I said to the man who had stayed with me: “we’ll take twenty minutes or so; we must be nearly there. Keep talking to me and I’ll talk to you – or we’ll both be asleep too.” We sat down and started talking – and that’s the last I remember until, about an hour later, we were all suddenly very wide awake as an ammunition dump started to go up about 200 yards ahead of us. Only ten yards ahead of us, I had seen a culvert through the embankment when returning to find my missing team, so we made a dive for that and rested in perfect security. In addition to the dump near the railway, there were three wagons of ammunition actually exploding in Sheria Station – so when that stout headed redhead of the 2/19th Battalion said quietly, “we’re on our own, Corp,” I would think we were almost rubbing our noses on the buffers of the first wagon. We had not seen a soul, either friendly or unfriendly, since leaving the Battle Headquarters. Mutiny, thank God.”

In the half-light before full dawn, we had the frightening experience of narrowly missing being skewered by our own side. The front line Brigade, left of the railway, was 180 Brigade, while right of the railway was 181 Brigade for this second day of the Sheria Battle – 7th November.

First to appear was 181 Brigade, with their left on the railway – the 2/22nd Queens – and they were not of course expecting to find anyone friendly in front of them. We were feeling very friendly indeed but letting them know this quickly enough to avoid being clobbered was a near thing.

Making not a sound as they advanced over the sand in open order”, with rifle and bayonet at “low left point, I was certainly glad that the Queens (known unofficially as the Bermondsey Bloodworms) were on our side.

At this moment, there had been no sign of 180th Brigade on the other side of the embankment so, to avoid another tense moment when they did arrive, I brought my whole party to 181 Brigade ground – and it was no doubt this, which caused us to miss seeing the Brigadier pass. It was late in the morning before I found the Battle Headquarters at the highest point on the first ridge beyond the Wadi Sheria.

I was delayed in finding Battle Headquarters because it was not where I expected it to be. Knowing the Brigadier would be on the highest spot he could find – certainly, the spot with the best view forward, I searched the ridge to the left of the railway, but there was no sign of him. I found him eventually on the ridge to the right of the railway – which was 181 Brigade ground. I think it was recognised that to cross a Brigade boundary was almost as serious as an invasion of foreign territory – but the Brigadier had a higher position and a better view of his own front from there.

We had been at Battle Headquarters about an hour with Turk shells skidding down our backbones to drop in the wadi behind us, when the Brigadier hurried away to the Headquarters of the 2/20th Battalion. The Brigade had come to an anchor; the Australian horsemen massed on a narrow front had tried and failed to burst a way out. He wanted to take a closer look and make a new plan in consultation with the Commanding Officers of the 2/20th and 2/19th, the front line Battalions.

No sooner had he left than the Officer Commanding the 2/19th Battalion hurried up the hill to consult the Brigadier, and was in discussion with the Brigade Major when a shell arrived in the middle of the party. Of the thirteen at Battle Headquarters at that moment, there were three killed and three wounded. The killed were Major Gray, commanding the 2/19th that day, a Sergeant, who I think had arrived with him, and one Runner. The Brigade Major was seriously wounded and two Signalers less seriously.

I think we seven who were left would have been happy to withdraw to the wadi behind us, but the thought of the Brigadier returning to his Battle HQ to find it had made a separate peace was too dreadful to contemplate. Two, however, were sufficiently quick witted to manage it and to appear almost heroic at the same time. Two men picked up the Brigade Major and staggered down the hill with him, treating him rather like a sack of potatoes, which cannot have been too good for a man with shell fragments through his left arm and into his chest on that side.

I was very puzzled afterwards because I could identify everyone on the Battle HQ at the time – except the two who saw, in the body of the Brigade Major, a legitimate means of getting off that ghastly hilltop. It was years later that I got the answer to the puzzle in a quite incredible way.

On 11th November about ten years later, say 1927, I was in a coffee house off Regent Street with a dozen others when, just before eleven o’clock, maroons warned us of the two minutes’ silence. This was rightly observed in those days and was tremendously impressive. We, of course, stood for the two minutes and on resuming our seats started talking of the war – instead of exchanging ideas on our own industry, in different sections of which we were all engaged and which was the purpose of our regular “coffee mornings.”

One of those present on this 11th November told a story of “early November” during the war – of one shell landing in the middle of a closely packed group on a hilltop in Palestine. I had known this man, whose name was Thomas, for some years in business. When he had finished his story, I said “That was 7th November 1917 and the hill was at Sheria, just beyond the wadi” and asked “What were you doing there?” He was an FOO with 180 Brigade Artillery and, together with his signaler, grabbed the body of the Brigade Major and rushed him down the hill.

Only two men in the world could have surprised me by telling that story (assuming that both had survived the last eleven months of the war) and yet the story, when it came, was told by a man, whom I had already known for a few years.

When, after twenty minutes or so, word came from the Brigadier to withdraw to the wadi (which was almost equally unhealthy), I dropped straight into the arms of my own “family” – the London Irish Signal Section, although I could have wished for a little more time to recover the wholly fraudulent air of nonchalance which is thought proper.

My story seems to be at variance with the History of the 60th Division by Colonel Dalbiac and published in 1927. He writes of 2/17th and 2/20th moving forward to secure a bridgehead over the Wadi Sheria at 1800 hours on the 6th and of Captain Travers with 2 ½ companies “soon after 1900 hours on the 6th”. Certainly, he does not say they secured the bridgehead, but the reader is left with that impression.

I have no doubt that the report received by 180 Brigade in the early part of the night of the 6th that a London Scottish patrol had reached Sheria Station was correct – however, this patrol clearly did not stay at the Station, but withdrew. Even Sheria Station was about 200 yards short of the wadi.

The first men to reach the Sheria Station and pass beyond it were the 2/22nd Battalion at first light on the 7th – the three men nearest to the embankment were caught in machine gun fire and killed about 100 yards beyond the Station – say 50 yards short of the wadi. These were the men, who had come across my party a few minutes before and we were watching them closely, every step they took, as we tried to figure out the position. Although they passed us when there was only a hint of approaching dawn, by the time they reached the Station about 200 yards forward, it was full daylight.

So there is no question of a bridgehead having been established beyond the wadi on the 6th. Another point I recall is that Lieut-Col Borton, commanding the 2/22nd Battalion, was awarded the Victoria Cross for his personal “recce” of the Wadi Sheria, and the ground beyond, during the night of the 6th/7th. He went across mounted and rode for about an hour or more during the night, watching the enemy preparing the ridge of our reception at daybreak. Although mixing with them, he was never challenged.

During the three days from dawn on the 6th to the evening of the 8th, the temperature were exceptionally high for November – something over a hundred degrees in the shade and, on one day, a hundred and nine was recorded. And, of course, there was no shade.

I think this highest recording must have been on the second day – the 7th – but I may be influenced in this by the fact that the 7th was certainly the toughest day of the three and the day that water shortage was most acute.

Shortage of water was a greater trial at this point than at any other time, although relieved temporarily to some extent by the capture of 25,000 gallons sunk in the sand near Sheria Station. Needless to say, we did not get the free use of this invaluable store ourselves, but we got something.

I think that it was at this time that I promised myself that if I ever got home again, the first thing I would do would be to go all over the house turning on all the taps – just for the pleasure of hearing the water running.

One certainly understood, as never before, the many Bible references to water. Man can go many days without food but even twelve hours without water – particularly at a time of great heat – is another matter.

Lance Corporal David Moore

David Moore has written to us about his father, Lance Corporal David Moore, who served with the London Irish Rifles during the Second World War:

“My father was born on 18th February 1917 in Airdrie. His Army number was 3249725 and he served in the Cameronians before joining the LIR and then joined the RASC when he returned from POW camp in June 1945 until he received his release papers on 17th February 1946.

Somewhere in Italy, Xmas Day 1943.

My father served in the 2nd Battalion, London Irish Rifles from 26th November 1942 until 13th June 1945. During this time, he was in Tunisia and Italy but was wounded and taken prisoner in January 1944. He was eventually sent to Lamsdorff POW camp and, in 1945, was forced to take part in “The Long March” across Europe. He survived this horrendous journey but, as with many old soldiers, my father wouldn’t talk about his experiences in later life – something I now very much regret especially as I spent my working life as an historian.

I received his Army records recently and these helped greatly in clarifying some details of his time with 2 LIR. He was indeed transferred to the Battalion on 26.11.42 and, according to his records, he fought in North Africa from December 1942 until the fall of Tunis in May 1943. It may be of interest to you that he was in E Company and was promoted to Lance Corporal in April 1943.

My father was subsequently sent to Sicily and you are very familiar with E Company’s movements there – then onto mainland Italy. He was with the 2nd Battalion all the way up the Adriatic coast and then was at Campobasso at Christmas 1943. Unfortunately, he was in 7 Platoon, under the command of Nicholas Mosley, on the morning of 19th January 1944 at Montenero Val Cocchiara when his platoon was overrun – he was with Mosley at his tent when a shell exploded nearby and was wounded in the side of the head and arm. Sergeant Sale was tending my father’s wounds when they were surrounded and captured.

My father is specifically mentioned twice by Mosley in his account of the event – firstly, his wounding and secondly, when he was a prisoner being led away by his captors. His army records note that he was taken prisoner at “Alvadene” but this is not correct, though I suspect that he was taken from the mountains near Montenero to Alfedena down in the valley. My only recollection of my father’s account of this episode is how angry he was at Mosley but I can only speculate as to the reasons. In one report I read, it suggested that, after Mosley was freed by Major Mervyn Davies, he would return to Montenero to face some “awkward questions”.

Further details of the German raid at Montenero are given below:

In the grip of an Italian winter high in the Apennines, 2 LIR were in the Castel de Sangro area where they took up defensive positions in blizzard conditions on New Year’s Eve. The nights were long, daylight was in short supply in the middle of winter and the weather was atrocious as they were high in the mountains and suffering freezing conditions.

In January 1944, he was a Lance Corporal in 7 Platoon of E Company of the 2nd Battalion London Irish Rifles with each company taking turns on the front line in exposed forward positions on a mountainside opposite the German line near the small town of Montenero Val Cocchiara.

There was some shelling on the night of 18th January – the prelude to the dramatic events of the following morning. The Germans had fired shells towards the positions held by 7 and 9 platoons so it appeared that they knew the soldiers were there and a dawn raid was anticipated but did not materialise and perhaps the soldiers dropped their guard. At 08.30, while L/Cpl Moore was with the Section Commanders at Lieutenant Nicholas Mosley’s tent receiving orders for the day, a shell exploded in or near the tent and all of the Section Commanders were wounded.

According to Lieutenant Mosley’s account:

“At Calvario on the 19th January at 08.30hrs a Platoon ‘O’ Group was assembled to receive orders in the Platoon HQ tent when a shell hit a tree about a yard from the door of the tent…. I immediately ordered the platoon into their trenches….. In the next trench Sgt Sale, himself wounded in the wrist, was trying to bandage L/Cpl Moore who was bleeding from the side of the head and the arm.”

By the time Mosley got out of the tent, the entire platoon had been surrounded and was being disarmed by the Germans. They had materialised out of the woods wearing white smocks armed with machine guns, grenades and with bayonets fixed. The men of 7 Platoon had no chance and surrendered rather than be killed. Lieutenant Mosley saw L/Cpl Moore and Sgt Sale being led away by the Germans as prisoners but escaped himself.

L/Cpl Moore was transferred from Alfedena to Florence where he spent a month in hospital having his wounds attended to. When he awakened on arrival, he thought that “he had died and gone to heaven” when he saw the nuns all dressed in their white uniforms and wimpoles. That period in “heaven” didn’t last long as he was then moved to the POW camp, Stalag 344, at Lamsdorff in Poland.

From February 1944 to January 1945: A Prisoner of War in Poland – a time my father didn’t say very much about. On his release, he said that his treatment had been reasonable, although food was in short supply. Red Cross parcels helped to keep him alive.

21st January to 2nd April 1945: Everyone was ordered to leave the camp and to begin what became “The Long March” west away from advancing Russian troops. L/Cpl Moore and the other men spent the next ten weeks walking between fifteen and thirty kilometres most days until he was finally released by Allied soldiers and repatriated to the UK. He suffered all the privations recounted by many who took part in and survived this horrendous experience including bitter cold and extreme hunger. I recall my father speaking about it only once, recalling the kindness he and a pal were shown by a German woman who cooked them a good meal when they had arrived with only a handful of rice they had asked her to boil up for them. By the time he got home, he was suffering from flat feet, damaged ankles and metatarsalgia as a result of prolonged standing.

14th June 1945: As a result of his injuries, my father was transferred to the RASC, where he remained until he was released to the Royal Army Reserve on 13th May 1946.

For his war service, L/Cpl Moore was awarded The 1939-45 Star, The Africa Star, The Italy Star, The War Medal 1939-45 and the Defence Medal.

1946 to 2009: David was happily married to Sadie, who he had married in 1942, just before he joined the London Irish Rifles and they were together for just over 66 years. They had two children, three grandchildren and two great grandchildren who knew him, and three further great grandchildren born since his death in Airdrie on 9th January 2009.”

A remarkable long life and cetainly well lived.

Quis Separabit.

RJ Prentice 2 LIR

We received a note and some photos from Colin Prentice, the son of Robert John Prentice who served with the 2nd Bn London Irish Rifles during the Second World War – he is seen below (directly behind Lt Searles) on guard duty with H Company for General Montgomery at Vasto in December 1943 as he prepared to leave 8th Army.

In his note, Colin told us:

“I remember Dad telling me he was in the London Irish Rifles and then later served with the REME.

My Dad was in the Territorial Army at Girdwood Barracks on the Antrim Road in Belfast and worked at Gallaher’s tobacco factory for over 23 years. When he retired he worked at the police authority in Belfast as security next to the Royal Ulster Rifles Museum in Waring Street.

I have enclosed a few photos of him, one with his two brothers who were killed in action in Burma.

Below, my dad is in the middle with brothers Alfred, left and David, right.

My Dad is top left below in the boxing team

Below, my Dad on the right with his men on exercise, with the REME I think,

I also remember my father telling me that he was a boy soldier.

He did get wounded himself in battle being shot in the shin and then was hit in the other leg – with a “dum dum” I think he called it. He was then injured in the head and had to have a silver plate inserted and I remember him telling me that the doctor said he might not last long but my Dad lived until he was 73.

At his funeral service in 1996, his army comrades – Joe Farrell at the front and Billy McCullough at the rear – would flank his coffin “

Quis Separabit

Brothers in Arms – Riflemen William Jenkins and John Wilson

We have been contacted by David Jenkins, the nephew of William Jenkins who served with the 2nd Battalion (2 LIR) in Tunisia and Italy during the Second World War. In a moving note, David told us:

“I have been meaning to contact you for a while now in relation to my uncle, Rifleman William Norman Jenkins, No. 7020240 and his friend Rifleman John Slater Wilson, No. 7023037, who were both killed by the same German shell at Termoli on 6th October 1943.

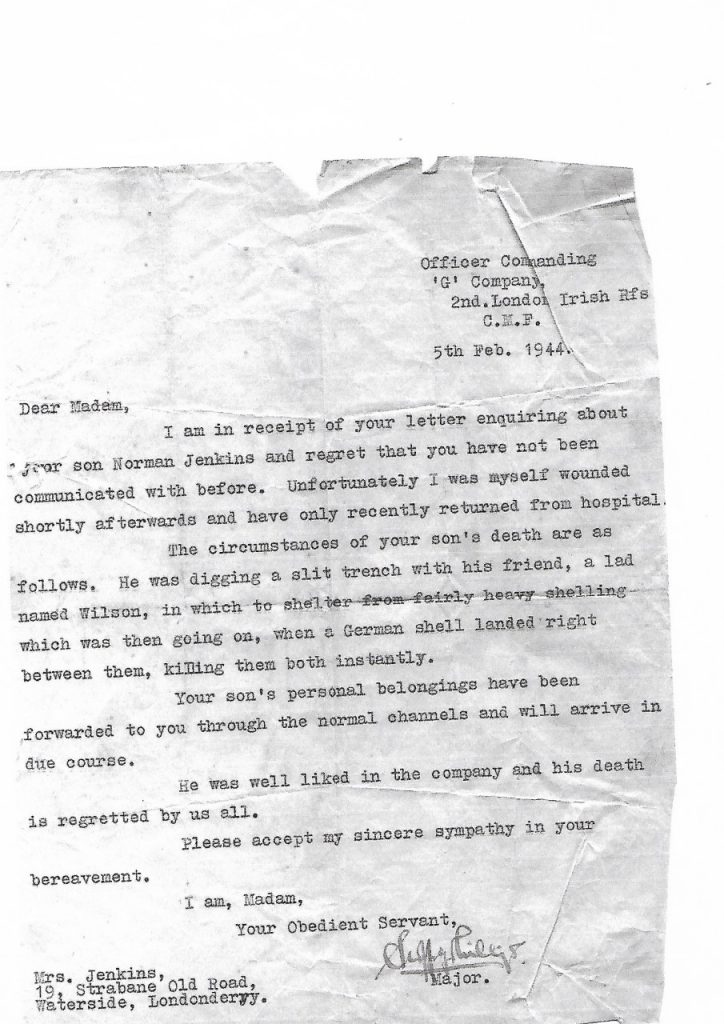

Major Phillips from G Company sent a letter dated 5th February 1944, to my grandmother detailing how William and his friend John were killed. Here are extracts taken from that letter:

Unfortunately I was myself wounded shortly afterwards and have only recently returned from hospital. The circumstances of your son’s death are as follows – he was digging a slit trench with his friend, a lad named Wilson, in which to shelter from fairly heavy shelling which was going on, when a German shell landed right between them, killing them both instantly. He was well liked in the company and his death is regretted by all of us.

William’s remains were then taken for burial to the Public Garden off Main Street near the Central Cemetery in Termoli. At a later date, he was then removed for burial to Sangro River Military Cemetery where he and John Wilson are buried beside each other.

William Jenkins was born in Londonderry on 3rd December 1919 and had two brothers and three sisters. His father, Samuel Jenkins, was one of eight brothers who had fought during the Great War. Samuel had served with the 6th Inniskillings at Gallipoli and Salonika where he came down with malaria but would recover and go onto serve with the Labour Corps in France. During the Second World War, he served in the Royal Fusiliers with the BEF in France and was rescued off the French coast 10 days after the last man had been lifted off Dunkirk. Following this, he served with the Queens Own West Kent Regiment Home Guard in Kent. In July 1941, Samuel and his company were billeted in a castle when he got up during the middle of the night, opened a cellar door and fell down a flight of stone steps. He was taken to hospital with concussion but died of his injuries the following day.

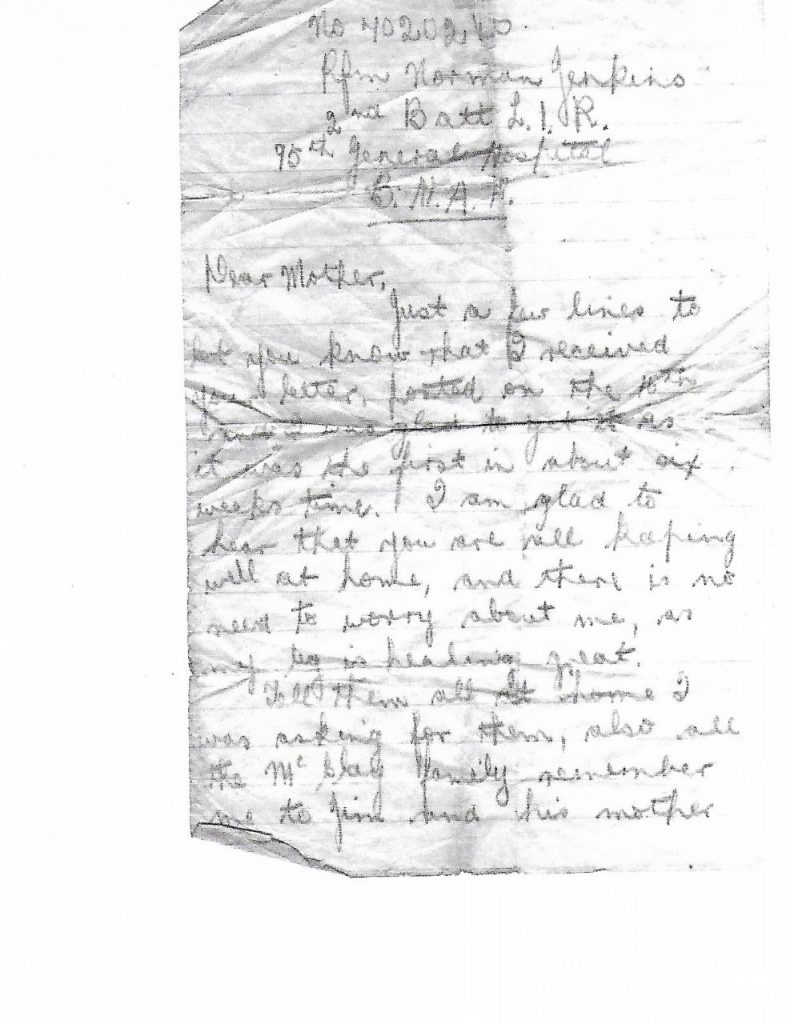

By then, William had joined the 7th Bn Royal Ulster Rifles – on 21st October 1940 in Londonderry, where he had been an Apprentice Baker. His records state that he was posted to 2 LIR on 29th August 1942 when they were located at Cumnock in Ayrshire. The records state that he embarked from Glasgow on 11th November 1942 and disembarked at Algiers on the 22nd. On 19th April 1943, when the battalion were positioned north of Medjez-el-Bab in Tunisia, William suffered a wound to his left thigh and was taken to the 95th General Hospital B.N.A.F., where he wrote a letter home stating that ‘there was no need to worry as his leg was healing well’.

He was discharged from hospital on 2nd August 1943 and joined up with the 2 LIR again on 6th September 1943 in Sicily before they departed for the mainland of Italy. Sadly, my uncle would be killed exactly a month later during the battalion’s fighting defence of the Termoli perimeter .

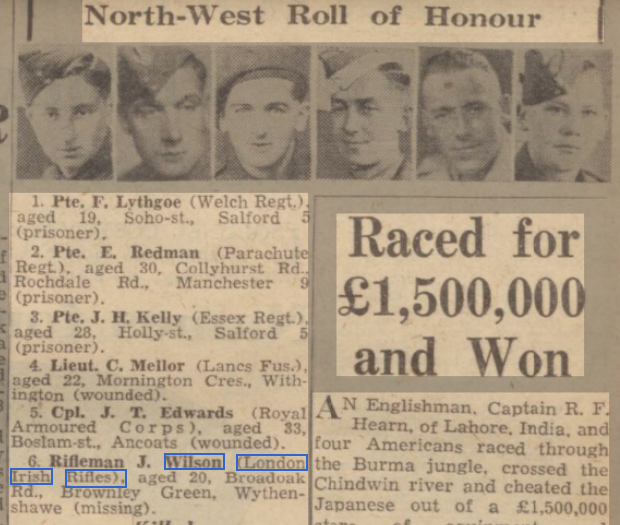

I have been looking for information about William’s friend, John Wilson, for over ten years now and it was only recently that I had a breakthrough. I was searching through newspaper archives and found John mentioned in a Manchester newspaper dated November 1944. He seems to have come from Wythenshawe and was recorded as being with the LIR but for whatever reason the article stated he was said to be missing. There is also a picture of him in uniform.”

We are most grateful to David Jenkins for sharing his family’s story.

Quis Sepaabit

Corporal George Willis

We have received a most moving note from Neil Willis, the son of 7017683 Corporal George Richard “Dicky” Willis, who served with the 2nd Battalion London Irish Rifles from 1940 to 1943.

In his note, Neil told us: “My father never talked about his experiences during the war but I managed to glean some information from him and my mother before they passed away. He told me that he had joined with friends from London and made the trip to Ballymena and signed up on 19th June 1940…

…My father did his basic training and saw his first action in North Africa but was shot and badly injured at Points 279/286 near Bou Arada in Tunisia on 20th/21st January 1943. The Germans overran his position and he sustained machine gun wounds to his upper left leg – one round passing through his thigh and then through his lower right leg. He was attended by a German medic who undoubtedly saved his life and the medic stayed with him until a counter attack drove the Germans back to where they had come from.

My father was taken to a field hospital and then he was shipped back to the UK before spending a long period of rehabilitation at Roehampton Hospital but unfortunately he had already lost his left leg from just above the knee. He used to say that his favourite memory of the time in hospital was being given a pint of stout each day!”

Corporal Willis was medically discharged on 30th September 1943 and, after working for British Petroleum for more than 20 years and as a bookkeeper in the Brighton area, George died of a heart attack at the age of 66 in 1981.

Quis Separabit.